I’ve just returned from a couple weeks’ stint as Visiting Artist at Central School Project in the unique town of Bisbee, in southeastern Arizona. I’m not really the kind of artist who has a regular studio-based practice, so I don’t usually think to put energy into seeking out and applying for residencies. I was invited to apply at Central School by artist/friend Laurie McKenna, who I often joke is the other artist who works with both people’s history/labor history AND penny smashers. An opportunity to go to Arizona in February was a chance to escape the doomy, relentless gray of Pittsburgh Winter… but it was also a rare chance for me to focus on a particular project that I don’t get enough space to focus on in the usual course of my life, and to find some space to stop and think about what I’m doing while I’m doing it.

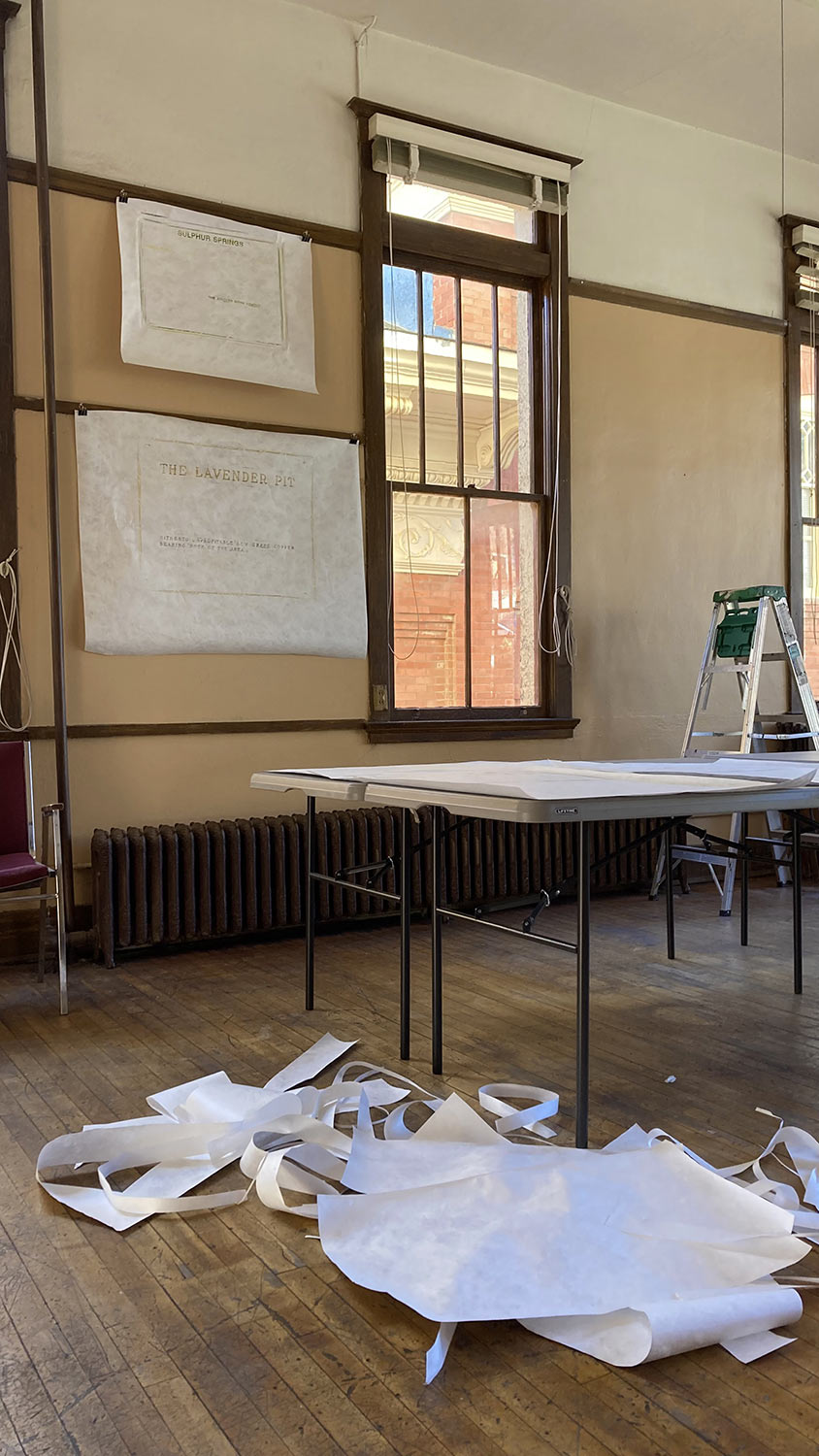

Central School Project is a former public elementary school, built in 1905, that now houses artist studios in each of its old classrooms as well as a couple of galleries and an upstairs theater. Being a “visiting artist” there is an open-ended situation, and Laurie and I had a lot of spontaneous phone calls throughout 2022 about what I was maybe going to get up to while I was there. I’ve struggled to make enough time to dedicate to printmaking in the past couple of years, so that was a natural angle to take, but it didn’t excite me. Instead, I really felt pulled to explore the landscape of historical memory in Arizona through whatever monuments and historical markers I could find. I decided that I wanted to expand the Redacted Rubbings project that I started in 2018, and do it in a place I’d never been. That felt like a challenge.

My work with the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum has me operating in rural environments more often than not, particularly those that were born of extractive industry that has since pulled up stakes and gone. Bisbee, Arizona is an old copper-mining settlement which was built into the landscape in a way that sets it apart from a lot of other towns in southern Arizona. It shares a historical tendency with Pittsburgh in that there are public staircases everywhere, and you can find old budget-rate workers’ housing precariously assembled along the steep verticals of the hills, some of which are still standing and some of which have been replaced by (or renovated into) modern homes. Bisbee also shares a historical kinship with Matewan (where the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum is located) in being a site of violent events a century ago during the long struggles to unionize the underground mining labor. Bisbee copper miners eventually unionized with the Western Federation of Miners, but earlier militant organizing was led by the Industrial Workers of the World. During the same era, in Matewan, it was the United Mine Workers (and occasional off-shoot, regional leftist miners’ unions) that struggled to bring basic human rights and dignity to the coalfields. The anti-union Bisbee Deportation of 1917, and the way it has (or has not) operated in the local memory felt eerily similar to how the 1920 Battle of Matewan sits in the collective consciousness of the Tug Fork Valley. The excellent film Bisbee 17 explores this often uncomfortable tension, in part through a community reenactment which reminds me intimately of the annual Matewan Massacre Drama that performs every May 19 in Matewan itself, for some 30 years and running. As a home base, the parallels of Bisbee felt comfortable to me, even if the specifics of copper extraction still feel like they border on alchemy.

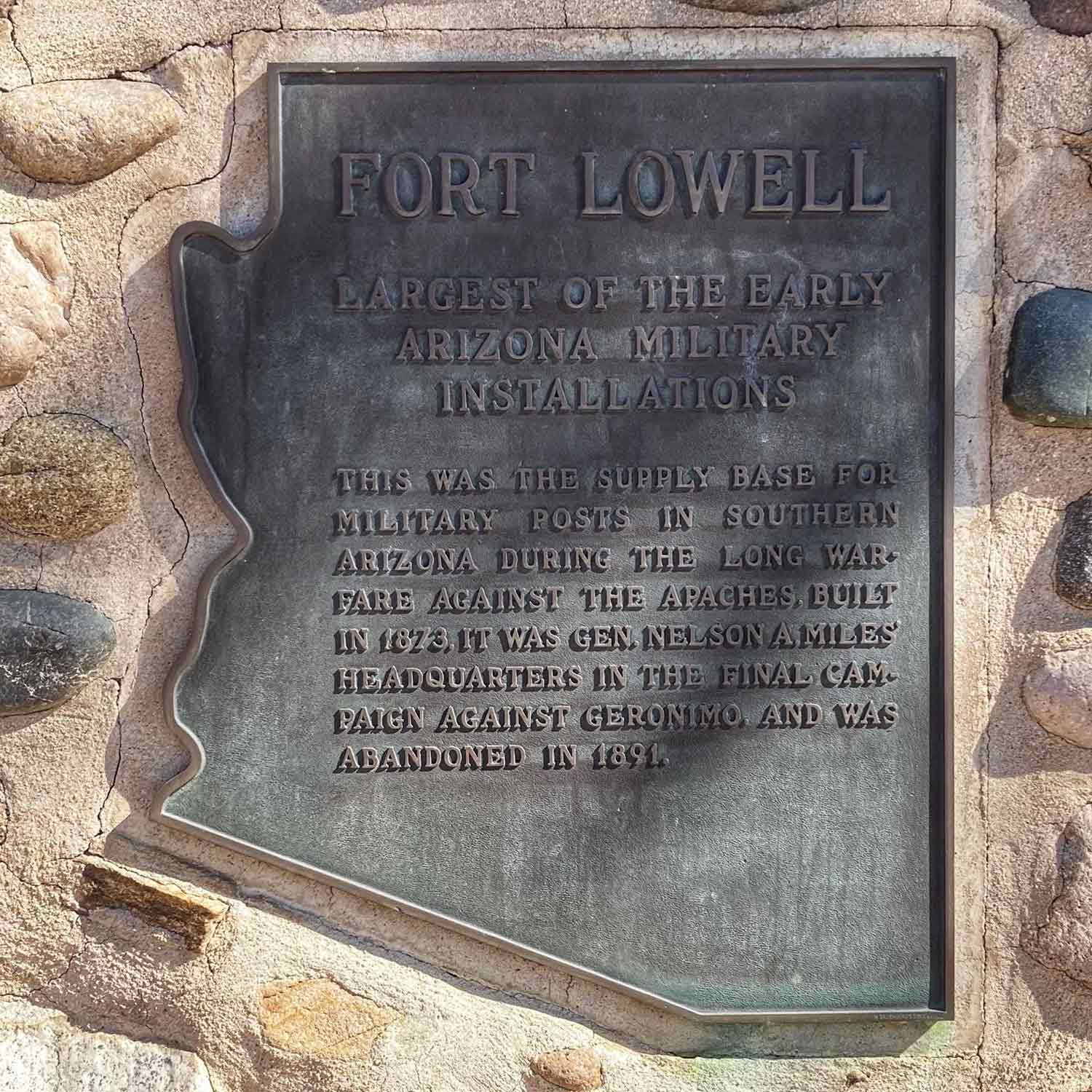

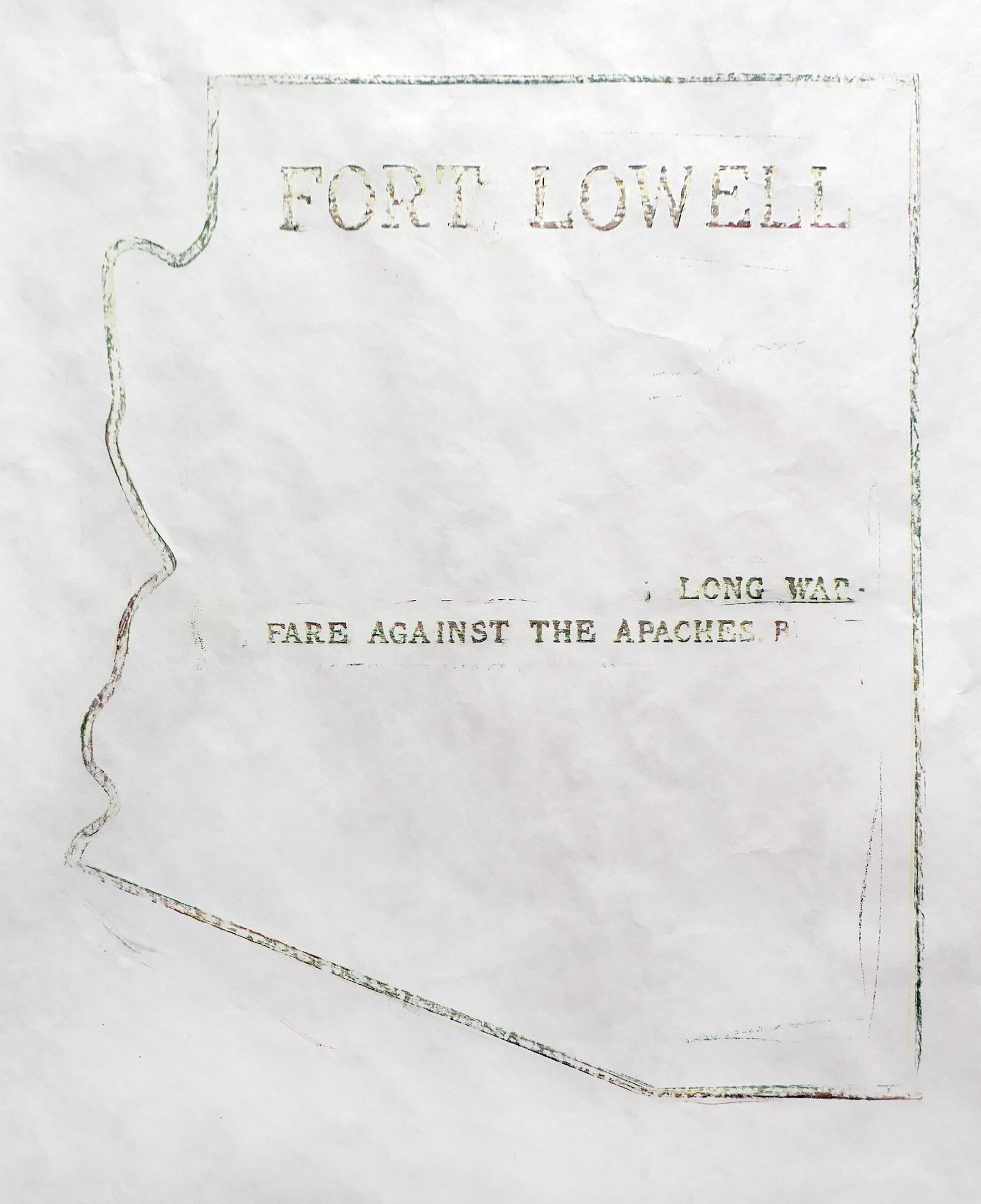

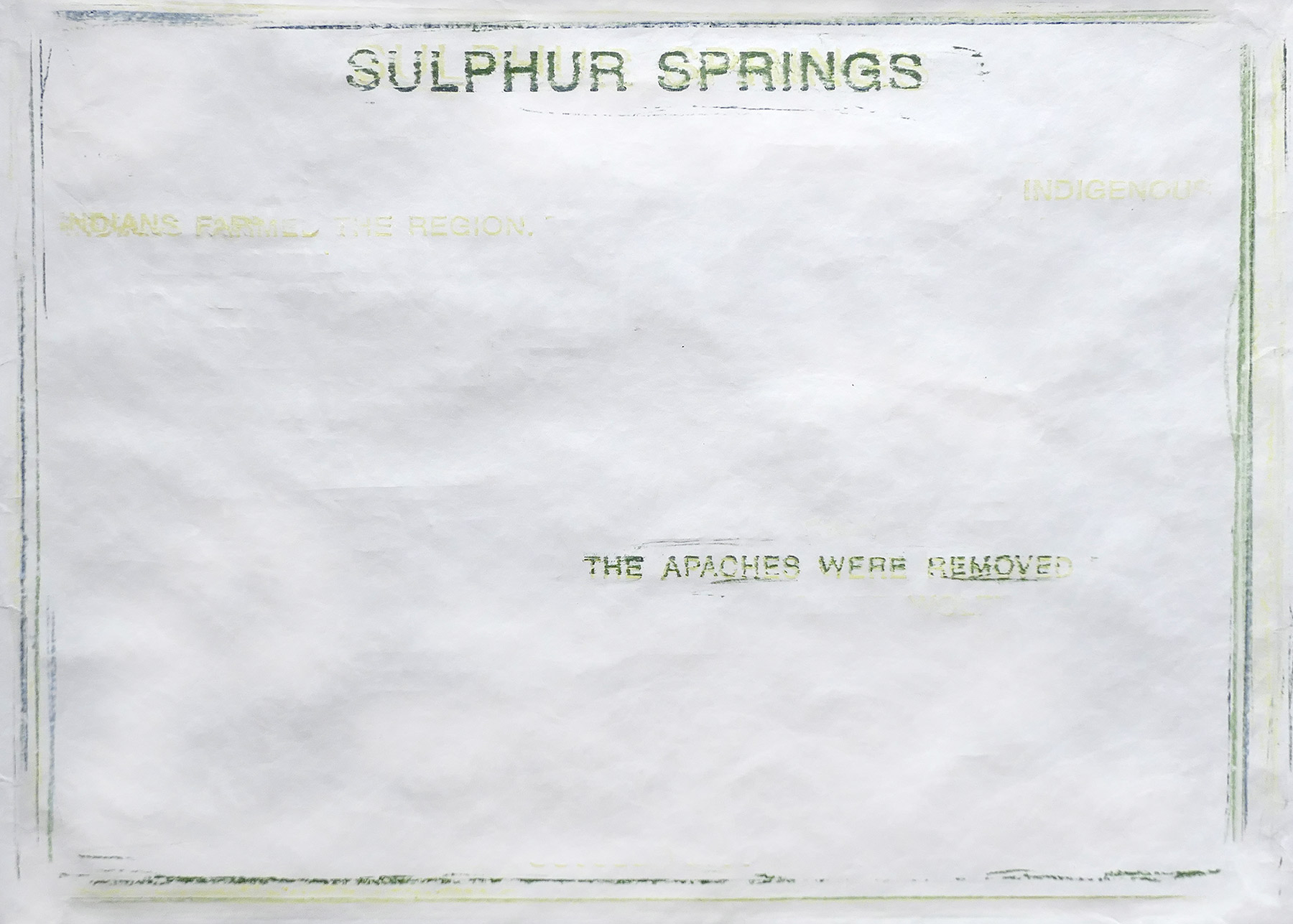

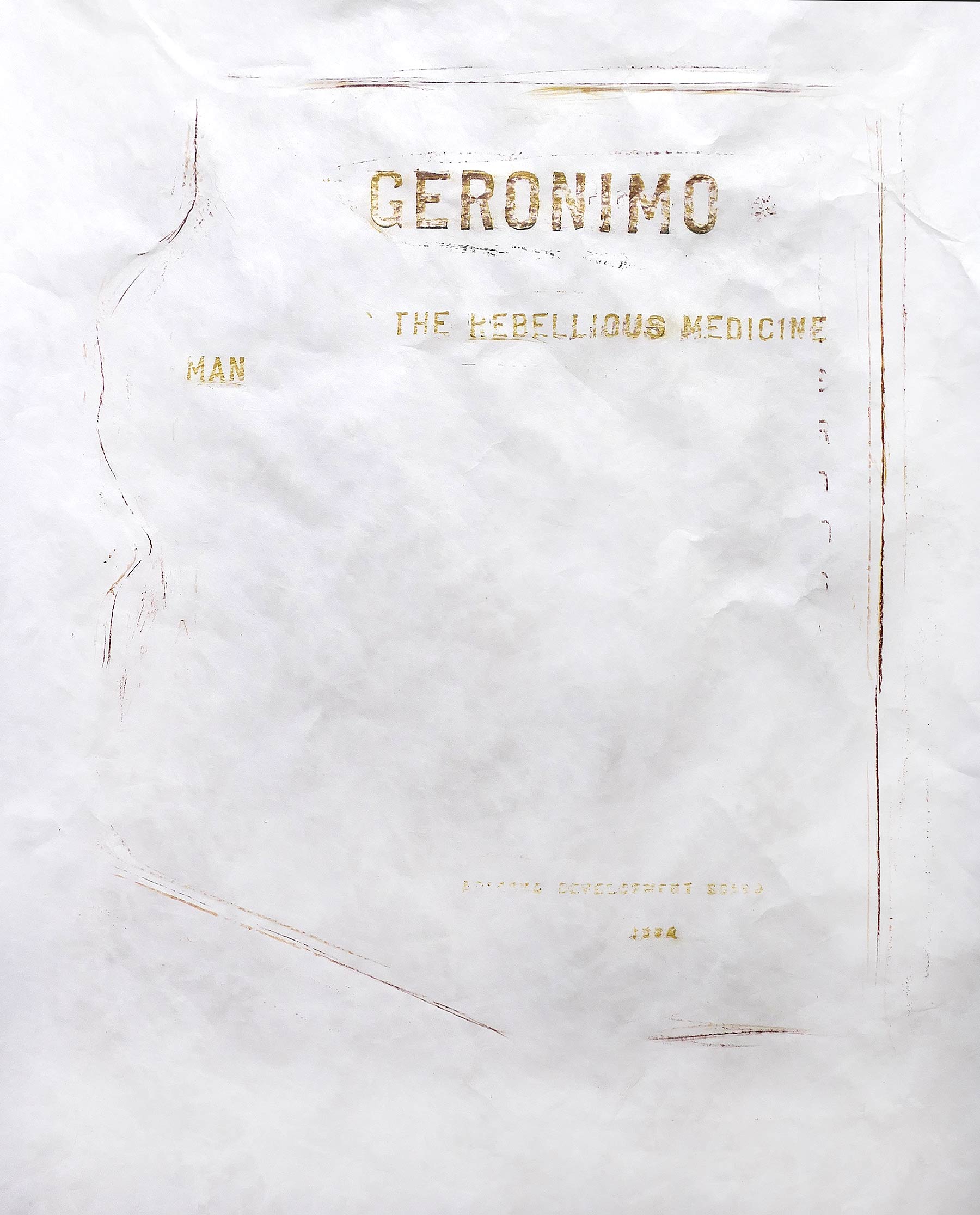

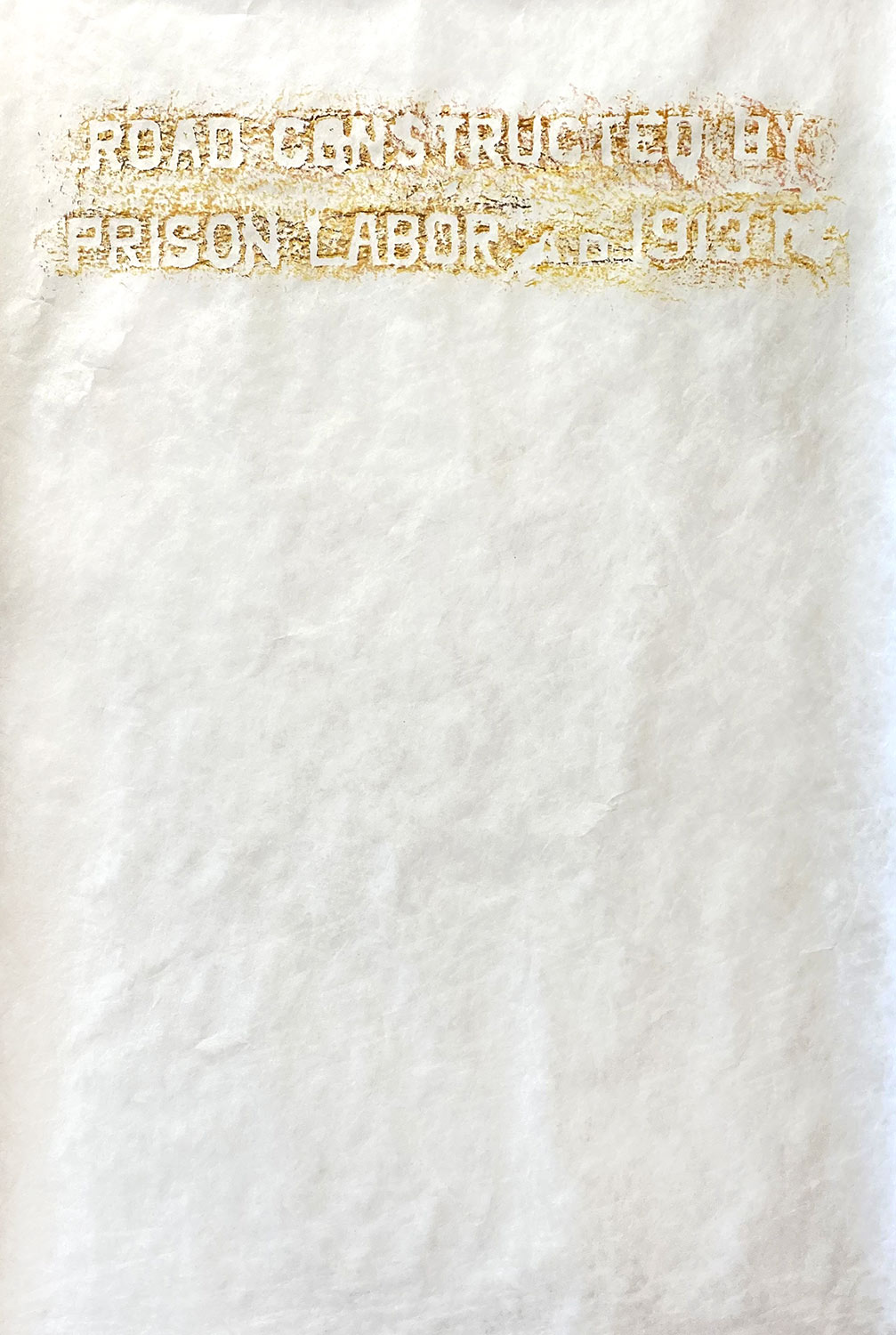

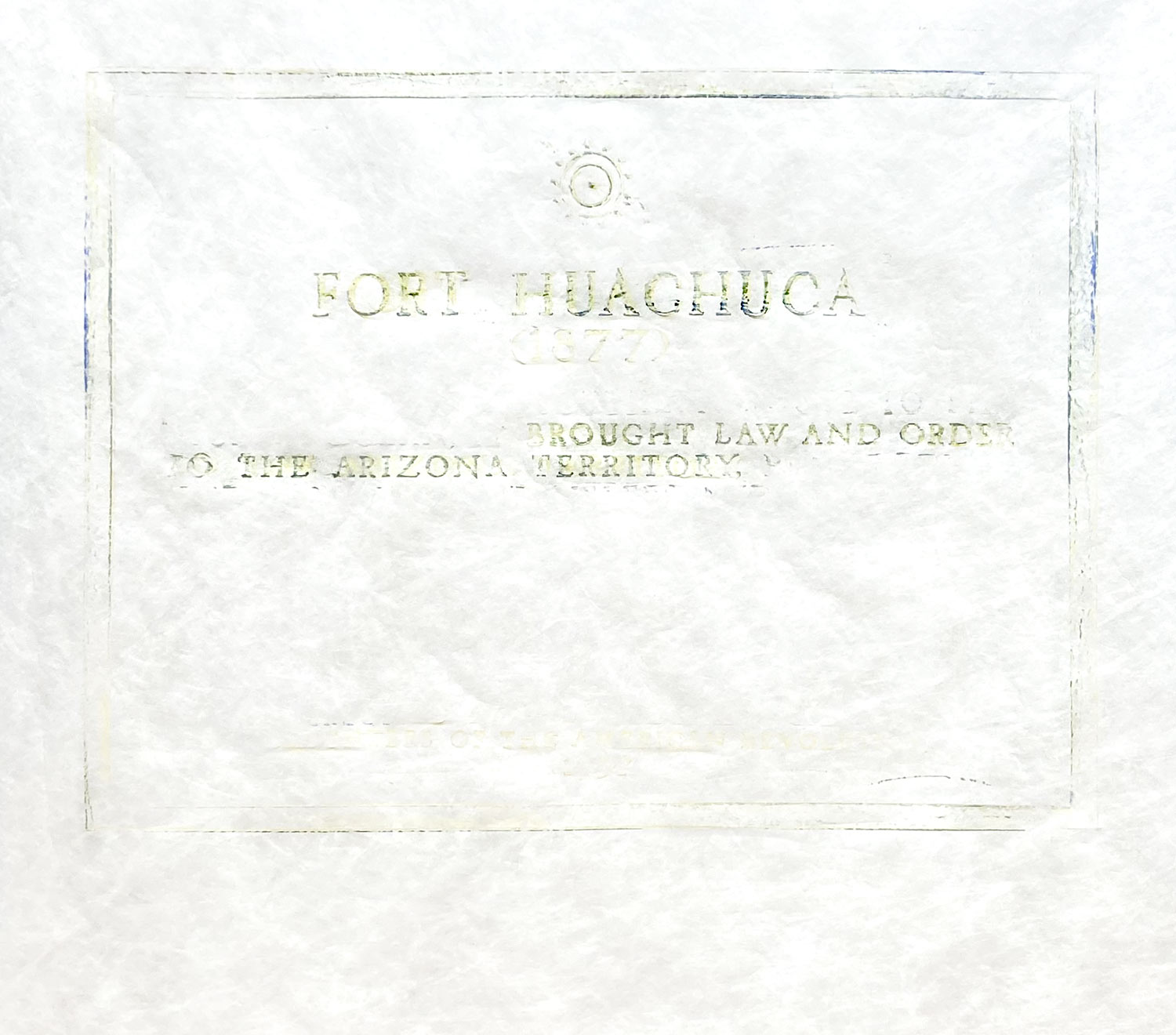

Back to the project: what I’ve been calling the Redacted Rubbings are selective wax rubbings on paper of historical markers and plaques. Begun in 2018, this is an ongoing project for understanding the language of state-sanctioned history through intentional erasure and omission, interrupting the provisional authority of the historical marker by disrupting static, languid interpretations of the plaque’s narrative.

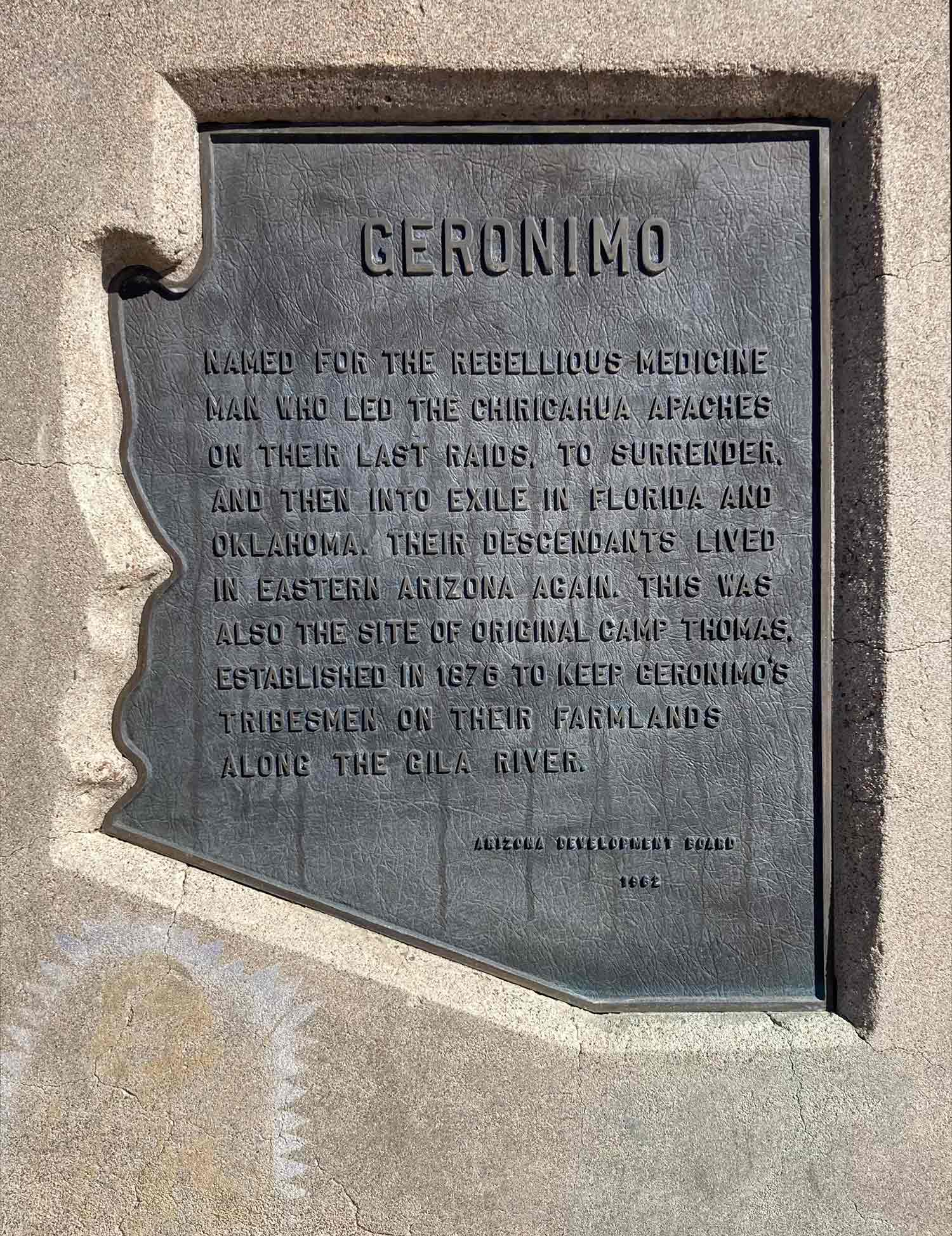

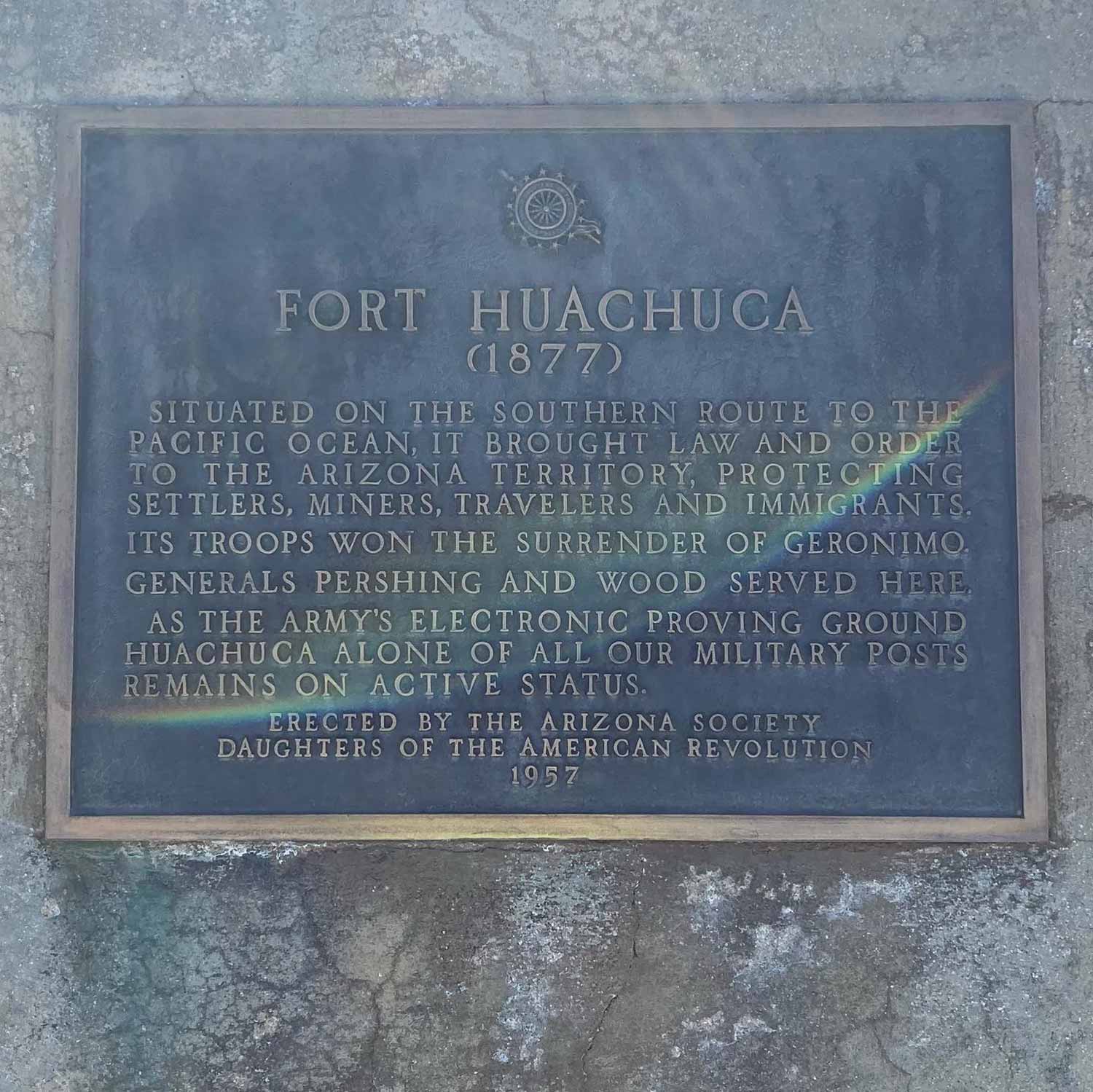

When I look for historical markers to make a rubbing of, I’m focused on finding plaques that feature language which glosses over or replaces colonialism, state oppression, and military violence with truncated accounts that marginalize the motivation and origin of popular revolts, disregard whole communities, neutralize the landscape, and other acts of erasure. The language on public historical markers and plaques is carefully crafted to guide our understanding of history, and their authority is often assumed. If we even bother to stop and read them (and let’s be honest, most of us do not), we can often take the existence of these markers and the narratives they proclaim as a given part of the contemporary landscape. Where did these words come from, who wrote them, and how did they come to be cast in metal, carved in stone?

These markers most often come from state-level historical organizations of some kind, but historical markers can also come from patriotically/ideologically-motivated organizations like the Daughters of the American Revolution, or from small localized citizen groups that want to memorialize something in a legible mode like a “this happened here” plaque. Whoever is behind any particular marker (and it usually says who, somewhere along the bottom), there’s a perception of authority to the voice cast in bronze, aluminum, or etched in stone. If you’re already critical of this kind of thing, you might arrive at every historical marker with an eyebrow already raised. But if not, then the language, the voice, has a ring of authority behind it that you might not immediately question.

This language has a real effect on our perception of the landscape of memory around us: if “the Apaches were removed”, for example, that doesn’t really tell us much about how or why, doesn’t put us in a position to begin to confront how settler colonialism shaped this continent, doesn’t even touch on the grief and violence hidden behind the word “removed”. If “the strike was broken” every time you read about a worker’s struggle that happened on the soil you’re standing on, you might begin to think that every strike has always been broken, and the horizon of collective action and potential for true solidarity might seem impossible to reach, an ideological fantasy. What I’m getting at is that, whether or not we all stop to read these plaques, their presence has an actual effect on our perception of memory and history. To some people I’ve spoken with, the very notion of a historical marker is already so fraught, they’re so certain of misrepresentation in any “official” public text, that they never even approach them.

In Arizona, I mapped out my work using the Historical Marker Database for research, pinning markers and monuments that I wanted to visit on a map, and planning drives that would incorporate at least two historical markers, if possible. Many of the spots in southeastern Arizona were incredibly remote, although when I arrived they were usually accompanied by a sign that pointed to the marker’s existence on the side of the highway, encouraging a contemplative stop. I’d often pull off the two-lane, park the car, and step out to the nearly complete silence of rural Arizona in February, broken only by the sound of wind, a bird I didn’t recognize, and occasional passing traffic.

As I work on a rubbing, I’m intentionally excluding, or redacting, most of the text on the historical marker to expose critical phrases (or, sometimes, just one or two words) that spotlight the heart of the plaque’s intentions. In this process, the guiding motives of the language can reveal themselves: Negative space dominates the large finished sheets of paper, and critical sections of directive language stand out nakedly for reconsideration. The Apache leader Geronimo, in one instance, has been labeled as “the rebellious medicine man”, and I extract only those words.

I do this work on-site in a deliberately visible, public performance. I bring palm-sized crayons I’ve made with wax and earth pigments, I wear a high-vis fluorescent vest, and I usually carry a ladder (although everything in Arizona ended up being within easy reach). The rubbings are done during daylight hours while wearing this basic costume that gives the suggestion of an anonymous municipal worker. Doing the work through the simple trespass of putting my hands on a historical marker brings up some of the tensions inherent in our conventions of private and public property: sometimes I think of this as part of the evolution of my practice from wheatpasting and stenciling on the streets when I was in my early 20s. I certainly learned, in those years, which creative activities were best done at night, and which could be done right in the middle of afternoon traffic when wearing the right costume (and being a white man).

Using Central School as a home base while traveling around southeastern Arizona, I realized that I hadn’t expected to be able to focus as much as I was actually able to. There was the focus of the research: often I see a historical marker while I’m traveling with my kit, or I’m on the road and look up nearby markers on the Historical Marker Database app (a real thing), and I go and find the ones that stick out to me. But its rare that I’ve been able to focus consistently on where I want to go, develop an understanding of how a whole series of markers plays a part in mapping a regional memory, and even begin to see similarities in the build and fabrication of state markers up close.

And there was also the focus in the moment, while making each rubbing on-site. Even though I knew this to be true, I hadn’t consciously realized that, once the crayon hits the paper, I’m usually working really fast. It’s not studio time: I’m making decisions quickly, making marks quickly, and sometimes battling uncooperative wind. In Arizona, for the most part, the rurality of several sites allowed me to take a breath and think clearly about how I was interacting with the plaque, how colors mixed, how the story was coming out on the paper. You know, studio shit, except on the side of the highway.

And I got to see so much of the landscape itself, beautiful mountain ranges that dominate the horizon in variance and stature so different from what I’m used to along the vast Appalachian range. I had to ask what most plants were, and I cruised constantly within range of the various grotesque mutations of “border wall” that run along the US/Mexico line and the attendant SUVs of Border Patrol.

Enormous gratitude to Laurie and all the folks at Central School Project, and in the town of Bisbee, for supporting me to take the time to do this work on your home turf.