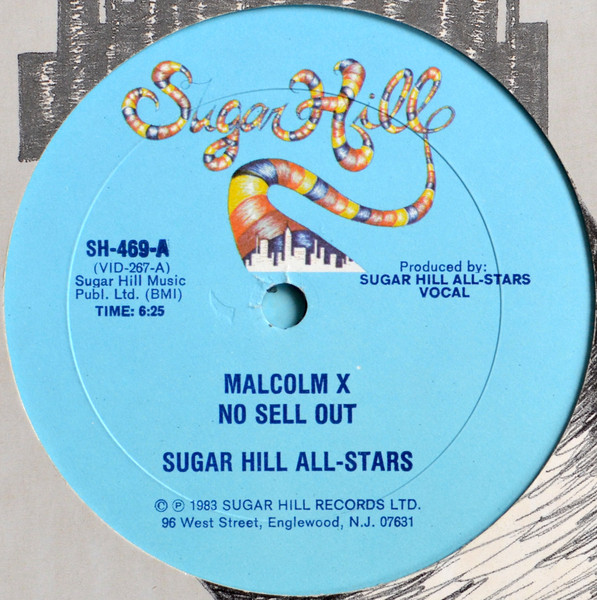

Keith LeBlanc died this week, leaving behind an extensive catalogue of music as a member of the Sugar Hill house band, Tackhead and Litle Axe. I interviewed Keith in 2015 for the Past The Margin book, so I thought I’d share this excerpt where he discused the making of his ‘No Sell Out’ single on Tommy Boy (and Sugar Hill, apparently!):

Keith LeBlanc: Someone was asking me how I came up with the Malcolm X thing [‘No Sell Out’] and I said, ‘I was in a place where there was nothing but groundbreaking things happening, so in order to even do anything it had to be groundbreaking for someone to take an interest in it.’ I was just trying to make a record and get paid! Where I really got the idea was I was heard Flash – he had some Dirty Harry speeches and he was running them over a groove he was playing on the turntables in a parking lot and I said, ‘Wow, I really like that effect – spoken word over a beat.’

Did you use tapes or records to source the Malcolm X speeches?

Sugar Hill had put out several records of his speeches and was supposed to pay Betty Shabazz, but they never did. I saw the speech records laying around the old studio, so I brought one home and checked it out and I thought, ‘This might be able to work.’ Drum machines had just come out, so I was struggling with that, because that was a whole beast threatening my livelihood at the time, so I ended up using the drum machine on it. To pull that record off I had to DJ with the tape machine, because there were no samplers. I had to use the reel-to-reel like a turntable and I’d have the engineer run the multitrack and I’d push the button at the exact right time to get the speech where I wanted it to record it in. We spent a couple of days doing that.

Joe Robinson owed Marshall [Chess] a lot of money, Marshall knew he wasn’t going to get it, so we took the money in [the form of] studio time. We used the studio time to cut ‘No Sell Out.’ It was hilarious ‘cos they weren’t even paying me no attention, and then we sold the record to Tommy Boy. I’d gotten Malcolm [X’s] wife involved, and she didn’t like the Robinsons. By the time they heard it on Tommy Boy, they were caught sleeping. Marshall played it for them and they didn’t know what to do. They finally realised that I’d made a record that could save their company and they didn’t have me signed to shit! [laughs] It’s one of those pristine moments that come along once in your life.

When the record came out, everybody was in shock. They had my name really big [on the label] and I told Betty I didn’t really like that, and she told me, ‘Let’s keep it, Keith.’ When I did that record, Malcolm was a taboo subject in the States. All these Black artists could’ve did things with her husband’s vocals and never did, and then this little white boy from Connecticut comes along. After they came out with the movie [Spike Lee’s Malcolm X] I was living in England and she had me do a show with her and took me to breakfast. She said, ‘Now imagine – I’m married to a prince!’ She was telling me I opened the door for all of that. That record made it okay to talk about Malcolm again.

When I did that record I had journalists from all over the world ripping me a new asshole, it was crazy. They were pissed off. ‘What are you doing with Malcolm’s speeches?’ I had to meet with Al Sharpton and all kinds of crazy stuff, and all people were sniffing around for money. I did a remake of the record later on and I managed to work it so Betty Shabazz, his widow, got all the money. She took that money and built a school in South Africa with Malcolm’s name on it. So some good did come from that record, ‘cos the first one didn’t really make any money, spent all the money on the lawyers, going to court. I remember thinking, ‘Sometimes information needs to come out and it doesn’t matter who makes money or who doesn’t.’

Why were you in court for the record?

Marshall had played it for Joe and Sylvia – they loved it and they just assumed they were gonna put it out. No one had talked to me. I talked to Marshall [Chess], I said, ‘I’ve got a meeting with Betty Shabazz, I’m gonna go play her the record. I don’t wanna have anything come out on Sugar Hill.’ And he agreed with me. Betty liked it and we signed a deal with Tommy Boy. They [Sugar Hill] just assumed it was their record, so they sued us! [laughs] They made a tape of it, slapped some stupid name on it and put it out, and then sued us. We ended up in New Jersey District Court.

We won, of course. The judge happened to be the D.A. that investigated Malcolm’s death, and he would ask our lawyer, ‘How are the gangsters doing this morning?’ Meaning the Robinsons! At the end of the day we had to give Joe Robinson a point on the record [publishing credit]. I didn’t even want to give them that, but Betty Shabazz said, ‘Give them a point, Keith. We won. Let it go.’ If it was good enough for her, it was good enough for me. Me winning opened the door. There was a whole line at the back of me that wanted to sue them. That was the last time I recorded anything at that place. I remixed it at Unique Studios in New York, ‘cos I had gunshots at the end of the record and Betty didn’t like that, for obvious reasons. I was young and pretty full of myself. Fletcher [Duke Bootee] said, ‘Keith’s probably the only one that coulda done that without starting a riot!’

The full version of this interview is also available in the limited-edition book, Past The Margin: A Decade of Unkut Interviews, available here.