I spent three weeks in May in Lubumbashi, the second largest city in DR Congo. The city was founded in 1910 as a commercial garrison for the nearby Etoile du Congo copper mine and the huge Union Minière copper smelter, whose smokestack still dominates the skyline. The surrounding region contains one of the most prolific mineral deposits on the planet, in an arc that stretches from the city of Kolwezi through Lubumbashi and south into Zambia. That deposit, known as the Copperbelt, continues to produce a significant percentage of the world’s copper, cobalt, manganese, and lithium, but I was in Congo to talk about another metal found in the copperbelt: uranium.

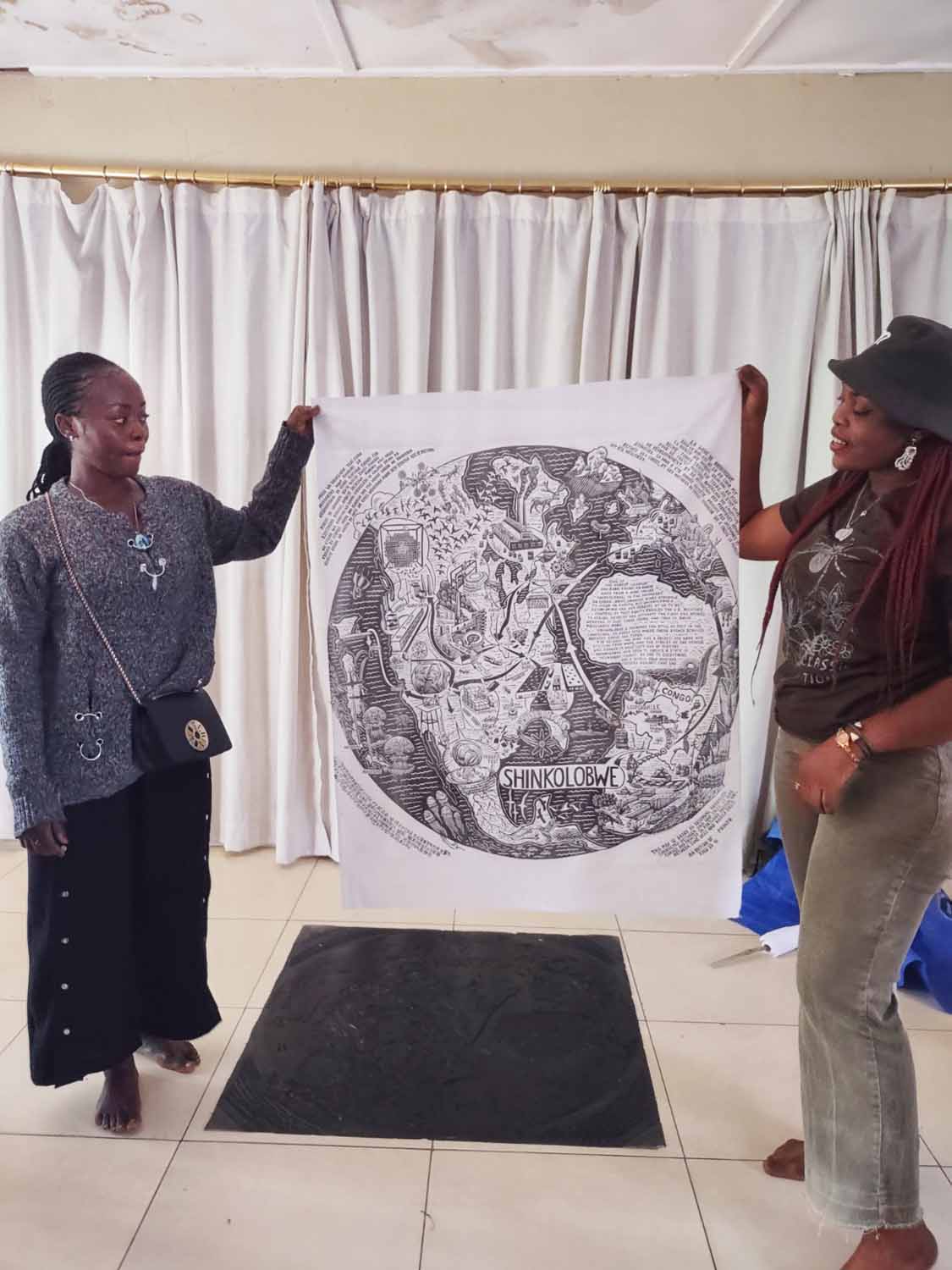

I’ve been working for several years on a large linoleum blockprint that traces the history of the use of Congolese uranium in the Manhattan project. A single mine located about 80km to the northeast of Lubumbashi produced the majority of the uranium ore used to develop the first atomic weapons, and then to build thousands more- in fact that mine was the major source of uranium for America’s weapons factories for nearly fifteen years. It is the most highly concentrated deposit of uranium ever found on the planet, and its name is Shinkolobwe.

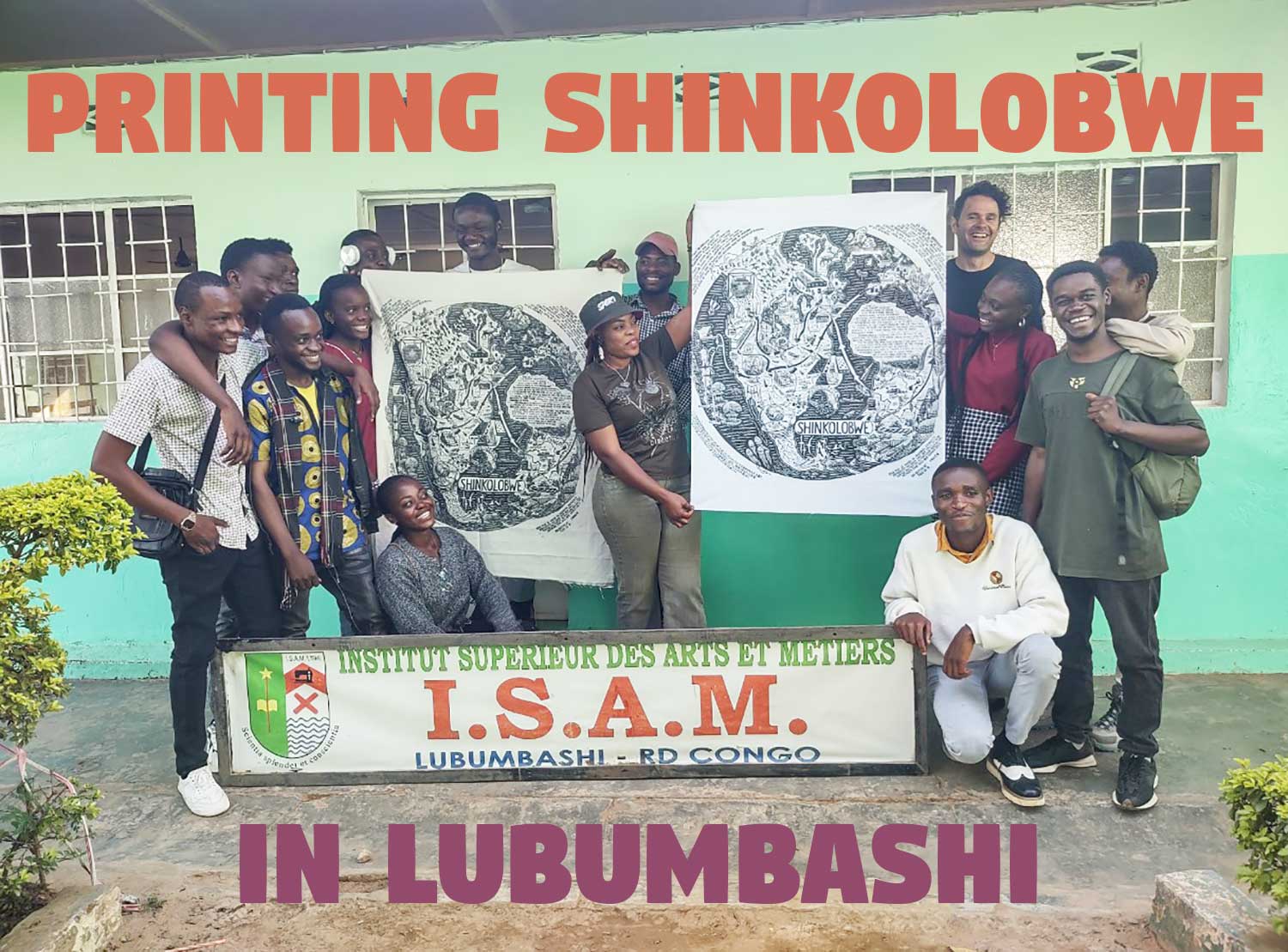

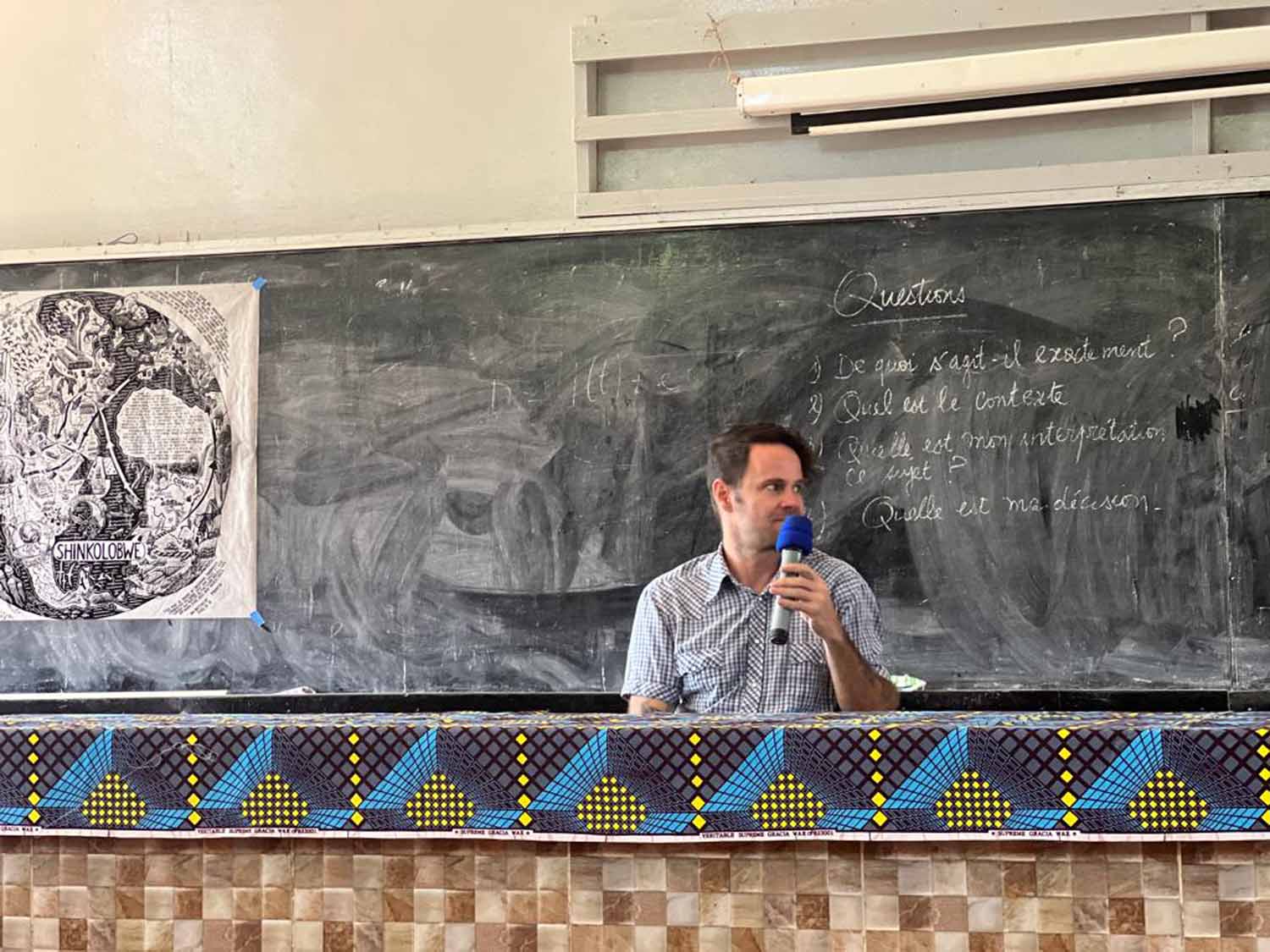

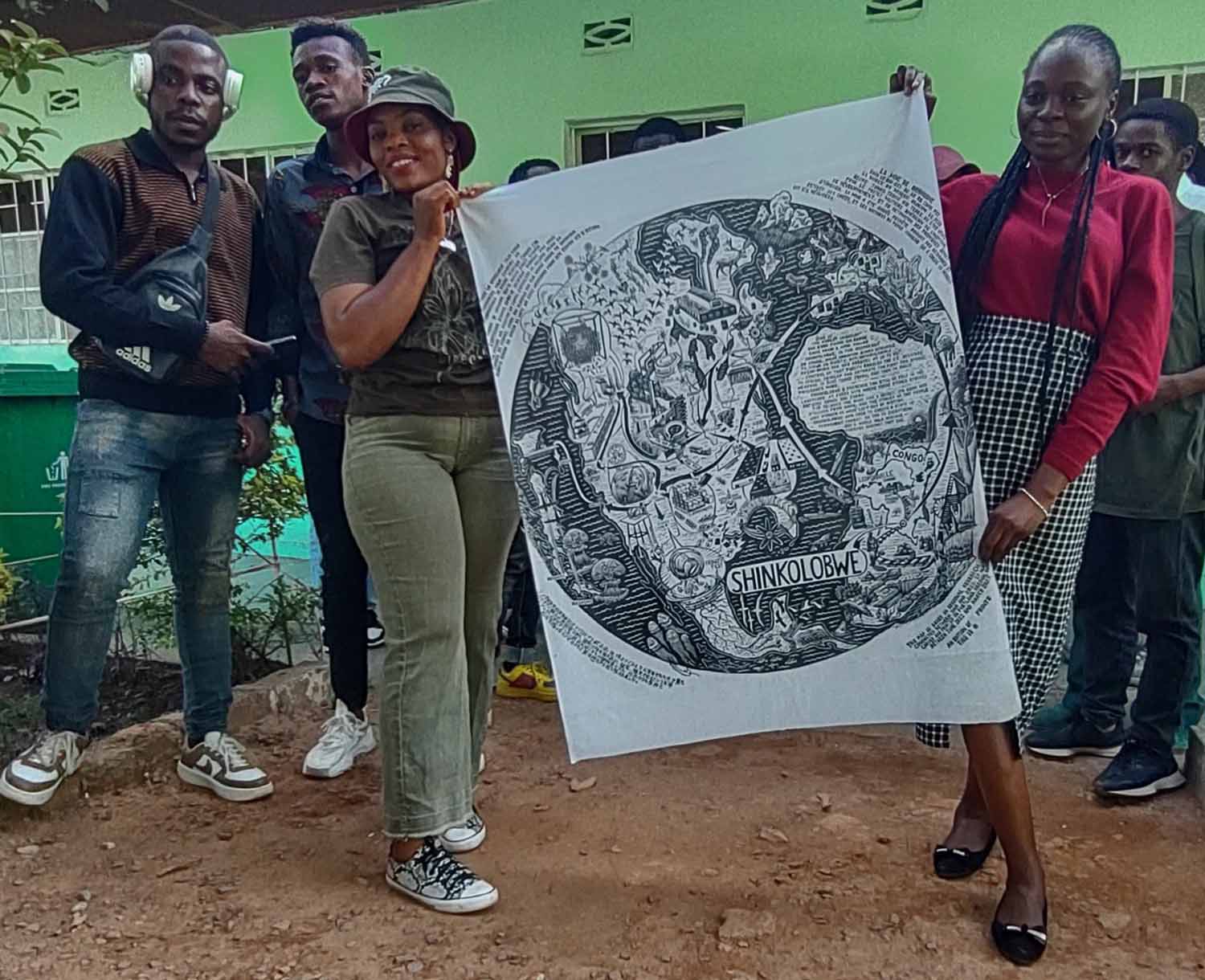

I brought the big linocut map that I made to Lubumbashi and used it, and the prints made from it, as the basis for six presentations to people around the city and beyond over the course of three weeks. I gave talks at Picha Art Center (my gracious hosts), Centre Arrupe, the University Of Lubumbashi and the National Atomic Energy Commission, and did workshops with the students of the Ecole Superieure des Arts et Metiers and with the women of Makwacha Village just outside of the city limits.

One striking thing to note about these presentations: in all cases, members of all audiences had heard of the mine, and were aware that its products had been used to develop the first atomic weapons. This is in striking contrast to audiences in the US, who have generally never heard the word Shinkolobwe and assume that all that uranium came from Canada or the Southwest. Some of it did- but Shinkolobwe produced more than 50{4e6932a869a7dc6e53218b6c4700540ba226cfd2b19b5c8dbd46dbf9a28a9134} of all the uranium used in weapons development in the USA between 1943 and 1958. Audiences in Congo were generally shocked to learn that the waste products of the industrial processing of Shinkolobwe ore are still causing public health problems and extreme environmental contamination at sites across the USA.

Something shared by audiences in Congo and the USA is the general lack of knowledge of what happened to the people who dug those ores. Working by hand with rough tools deep inside the most highly concentrated uranium ore-body on the planet certainly produced some health consequences for miners, and the health of those miners was part of very early studies on the effects of uranium ore exposure- but those studies had to fulfill themselves in other mining centers in Gabon and Niger after the war, because the strict regime of secrecy surrounding Shinkolobwe precluded too many questions being asked.

The health of Congo’s mineworkers has long been ignored by a world hungry for minerals, and in the current rush for battery metals for the so-called “Green Transition”, the rates of exposure to toxic metals by some of the poorest and most highly exploited people on the planet are off the charts. The first ever study of the health consequences of exposure to cobalt was released in 2020, based on research conducted in Congolese mineworker communities near Lubumbashi. The story of the miners at Shinkolobwe, however, remains lost, still trapped in the weird historical momentum of that regime of secrecy established by the Manhattan project in the 1940’s, when the mine’s name was stricken from maps and all mention of it in the press was forbidden.

This project is a work of historical memory, intended to create connections within the worldwide community of people affected by the mining and use of Shinkolobwe’s ore- which, at the end of the day, is all of us.