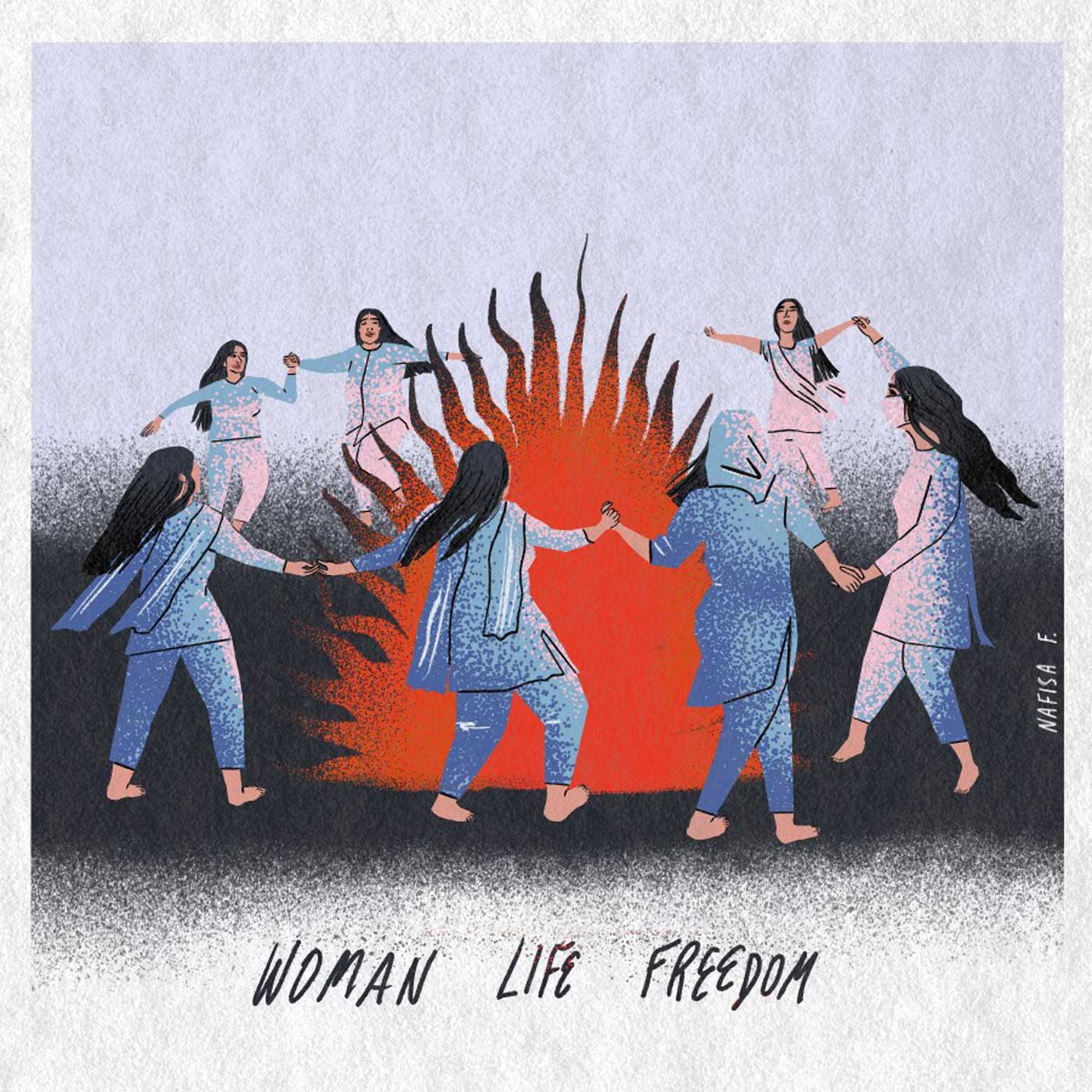

Our tenth Dispatch finds us in discussion with Nafisa Ferdous (IG:__petni, website:nafisaferdous.com), an illustrator, political artist, and activist who lives in New York City.

You can find all of our previous Signal:Dispatches here.

Will you tell us a little about yourself? Who are you? Where do you live?

My name is Nafisa Ferdous (She/Her), I was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh and grew up in Queens, NYC. I am in my 30s and started making art publicly pretty recently. Up until 2020 I was working in a lot of feminist movement organizations and doing research in Asia and East Africa. So, I spent most of my 20s running around, learning, getting really overstimulated and sucked into this world of ‘transnational feminism’. To put it in a nutshell, it’s a small, but diverse, circle that includes on one hand elite advocacy groups and corporate “NGOs”; and on the other more ‘progressive’ philanthropies and legitimately grounded national and regional people’s movement organizations, collectives, and unions. This coalition of folks work across borders on things like decriminalizing homosexuality, access to safe abortion, sex workers rights, gender affirmative and universal healthcare, disability justice, climate justice – all of this again on a spectrum from being very explicitly anti-capitalist and solidarity-based to more technical human rights and policy-ey. Unfortunately, I let that define me for a long time and got really burned out. It took me forever to find art again (which I’ve been doing all my life but for myself) and see it as a way to continue participating in movements, to find and build community, and also to express myself creatively/politically. Not just as this work-horse ‘professional’, like before. I’m also self-taught and figuring things out as I go.

You have a distinctive sense of form, your subjects’ bodies have weight and agency and your pictures of groups are really fun to look at, as each person in the picture has something different going on. With that in mind I wanted to ask you about one of your illustrations specifically–the Lodhi Garden piece. I love how you encompass narrative, humor, sexuality, into a larger idea about public space and privatization. It’s a very fun and funny drawing, almost like a kid lit illustration, with a lot of details that reveal themselves with repeated viewings. So… what is the Lodhi Garden drawing? What stories were you trying to tell with it? How did you construct the drawing in your head? And you mentioned it was one of your favorite drawings of all time-why?

Yesss! This is one of my favorites!! I worked in India for 4 years and I was in Delhi where Lodhi Garden is during a time when Section 377 ( a colonial-era law criminalizing sexual “acts against nature” and homosexuality) was being overturned. The organization that I worked for was involved in this struggle, and I lived in a queer house, and the whole country was/continues to be in the middle of these contestations. I think in a lot of Southern countries too, privacy can be a luxury, because you’re probably living with your family… Queer people, young people, all kinds of people have to carve out their own liberatory spaces. Public parks can be part of that constellation of spaces because it’s where lovers hang out, queer people cruise, where folks have a level of sexual autonomy more than at home or other highly surveilled / morally policed places. Campuses for example are highly policed. Pinjra tod is a movement led by young feminists on college campuses against gendered curfews and sexual violence. There are organized movements against moral policing (377, Pinjra Tod etc.) and there are more autonomous examples of resistance at say… parks! This is the spirit I was trying to draw. But also I like art that is accessible and fun, which is why I think a lot of my work is cartoony (I love cartoons and comics!). This piece was an ode to queerness, agency, pleasure, and all the folks who practice it despite state violence and fundamentalisms, but fun.

Your Tipu’s Tiger piece is really gorgeous and powerful. Will you tell us about the background of this drawing?

There are some things you learn about as a young person that stick and this object, a crank operated tiger mauling a British East India Company soldier from the 1780s, was one of them. The tiger has a pipe-organ that when turned, simulates the noise of the soldier screaming! I studied post-colonial theory and history in undergrad and sure, it was helpful for me to grow, but it was also deeply alienating from real people and humor-less. If we think of the actual tiger/toy as art from a time where the British hadn’t yet formally colonized the subcontinent and all kinds of resistance movements were bubbling, then we see it as a popular object of resistance. British art usually chose a lion as the personification of imperial might and Britishness, sometimes the lion was protecting a hyper-femme semi-nude lady–symbolizing an aspect of purity or white supremacy. And sometimes the lion was protecting the woman from a wild tiger which, yep, was the “Eastern” other needing to be civilized and all that. Tipu Sultan was a regional ruler from Mysore, in Southern India who was one of the early resisters of British East India Company’s encroachment. He had this toy commissioned during his three major military campaigns against them. I mean Tipu Sultan shouldn’t be pedestalized as a singular hero, he was after all a landlord and a king, but I love how Tipu’s Tiger was a cheeky “fuck you” to the British. It’s on match boxes, trucks, I think there’s a postage stamp, and is part of the Indian imagination now. The actual machine is also in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, unironically.

Your color work is radiant . What are some color inspirations for you? How do you go about deciding color?

I think color can be an invitation! I think color is “vernacular” and what I associate with big, organic, public life. Since I grew up between Bangladesh and the US, I was really influenced by the stark contrast of this boisterous communal life (most of my family in Dhaka live in apartments or houses with multiple generations and open doors–as a kid I could run from one apartment into the other because the doors were rarely closed) and my very nuclear childhood in NYC. In NYC, architecturally you have grids, concrete, regulated, color coded apartment blocks. In Dhaka you have turquoise gates, green mosques, pink skies, yellow houses, greenery everywhere. I think that bombastic sense of color is because of the emotional attachment I have to the subcontinental community and climate.

It seems like you’ve come to making art (at least publicly) a little more recently? Perhaps following a career in NGOs and non-profits (loaded terms–I know!). If this is the case, what made you make the jump? What were you hoping for? How’s it going?

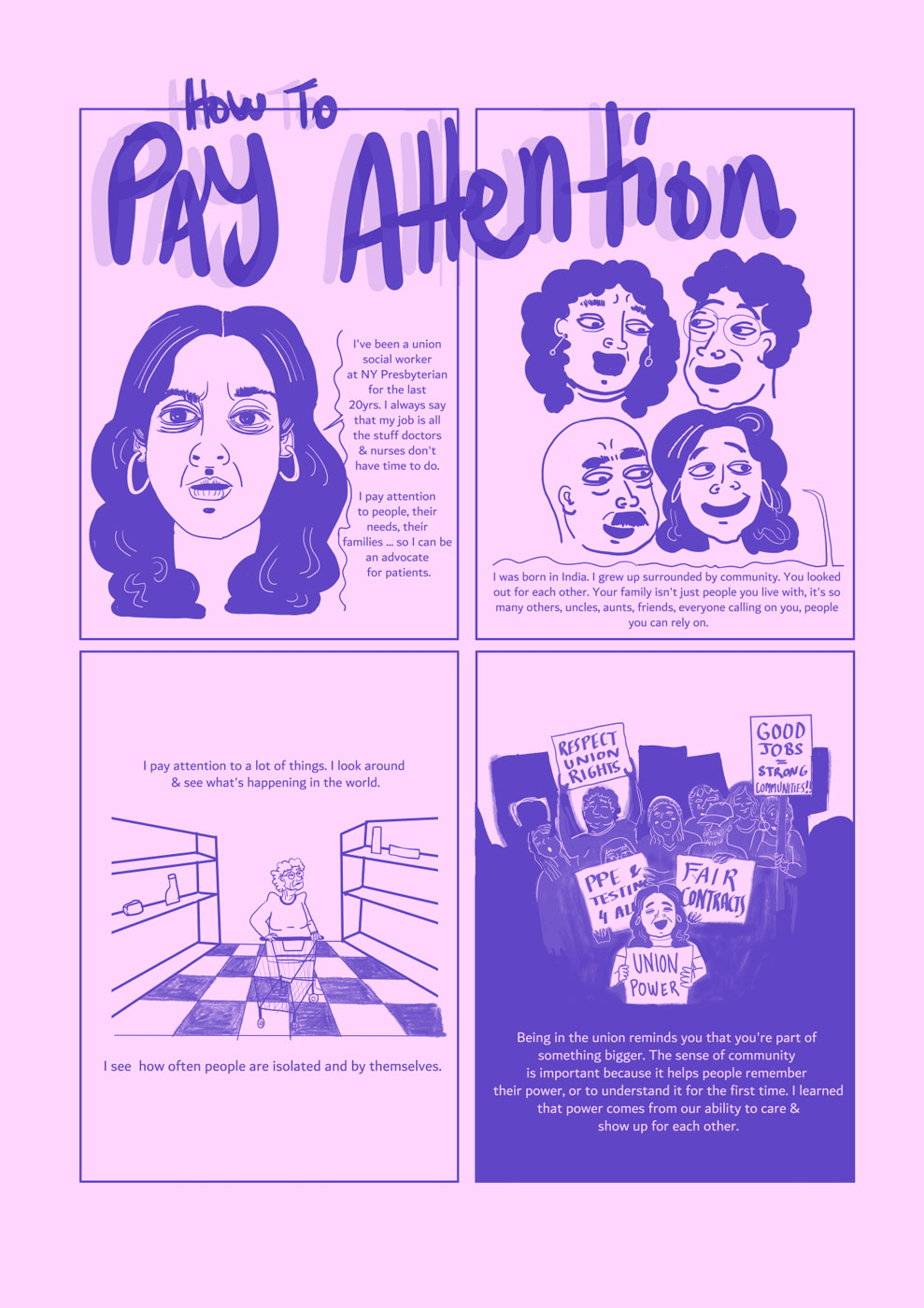

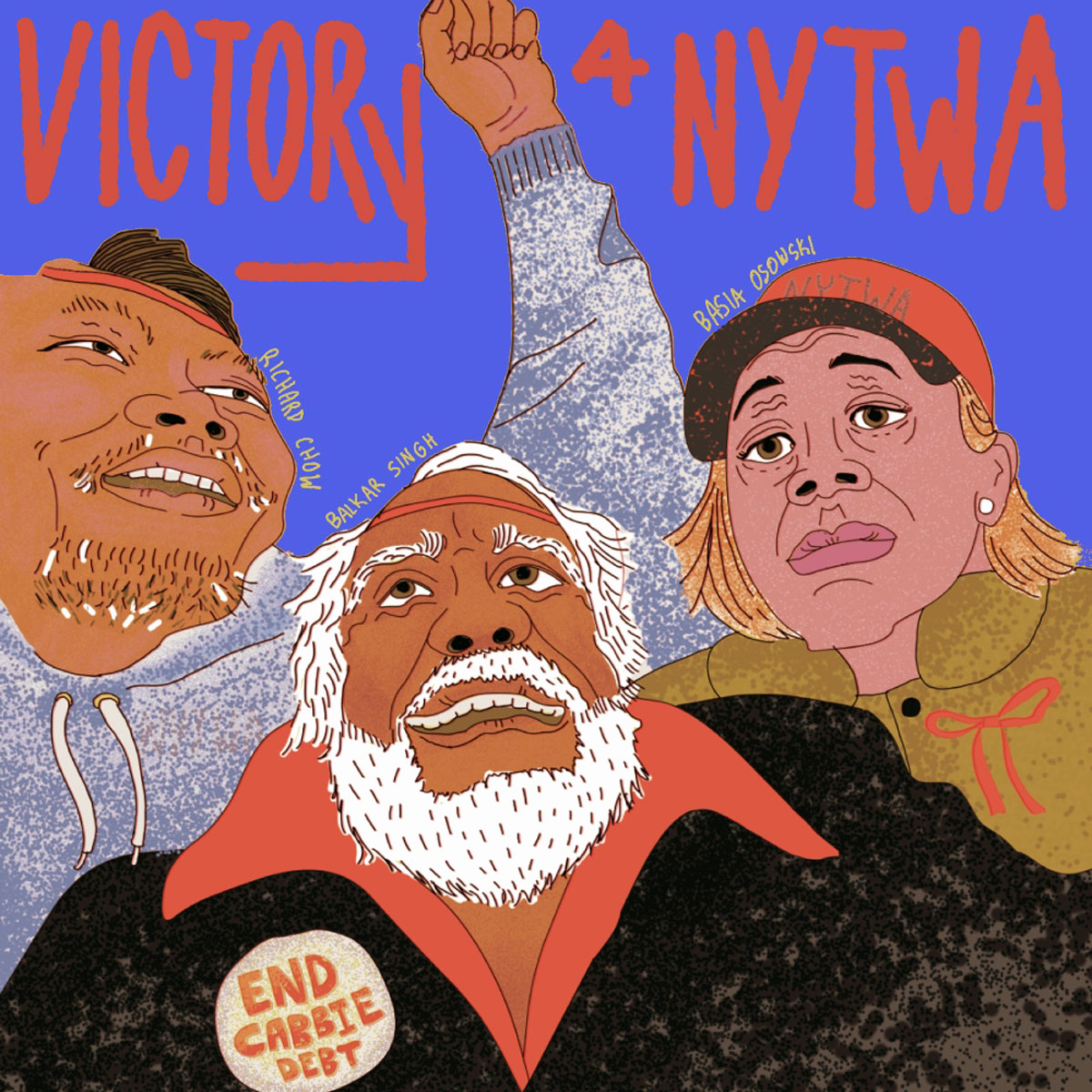

It’s going well. Also I had really low expectations to begin with. I didn’t want my art to become a hustle so I took a more exploratory approach. The first year I made connections with mutual aid and artist-run coops and storefronts in Queens. This year I decided to stop selling prints and doing too many “events”. I’d rather build relationships with community organizations and projects that I care about and spend more time on developing narratives and political comics. What helped me become more public was actually a political comics class I took at Mayday Space, a community center and organizing hub, taught by Seth Tobocman. We started right before the pandemic and I ended up getting covid and dropping out, but despite that, it was the first space I ever workshopped art that also tried to tell meaningful stories. For example, we interviewed folks from 1199-SEIU health care workers unions and turned them into interview comics. Similarly with folks from Picture the Homeless, a membership based organization advocating for justice for houseless people in NYC. That class kind of lit a match for me, to be like, ‘Oh this is a really great way of bringing my politics and art together.’

You mention a couple of times about trying to make low ego art. What does this mean? How do you do it? Any lessons learned in the process?

I think some parts of the internet are dominated by neoliberal influencer culture and it makes people have a scarcity-mentality and be unnecessarily competitive. When I started out, it felt like there was this race to commodify your identity and sell stuff. The louder, prettier, or more unique you are the more “successful” you present. Who wants to present as “successful” in neoliberal racial capitalism, though? I think cultural change work and community-based art is different, and I call it “low-ego” because I hope it’s more about interconnections rather than the self. It took me a second to find my people. I still am finding and building with people, and that’s what’s motivating me these days in general.

On the flipside, I feel like illustration and commission work is (for me) a sometimes perilous process in having my ego battered into the ground, with revisions and micromanaging from ‘clients’. I’ve had to, at times, learn how to assert more ego than I am comfortable with, to push back a little. Is there a tension between voice and ego? How do you navigate that?

Hehe. I have only had 2 commissions in the traditional sense. Everything else I’ve made for myself, with friends, or through grants and projects. I can talk more from the client side in that sense. In 2021 I was managing this big website project on young feminist movements and leading a 5 person team. I really wanted to hire a queer feminist illustrator so we could set the values and visual language together. Most of my colleagues hadn’t engaged in this type of feminist collaboration (like they always saw consultants as people they had power over and created this unnecessary hierarchy) so I noticed how they were micromanaging this awesome artist. I asked my colleague to sit in on a feedback session with me and the artist as an observer/note-taker. We were super lucky to have that artist on our side, and I think this view of them as a contracted worker is so antithetical to the value and perspective they bring to projects. After that feedback session with the artist, I asked my colleague to stay on the line and debrief what they observed. Instead of just explaining that you have to respect, trust, and give political-artists space to interpret briefs, I wanted to model it and show my colleague what a more peer-relationship can look like. Unless there are big substantive changes (early on in a process, not later!!!!), it’s not the end of the world if there are 5 leaves instead of 10 on a header. People in general take their work too seriously and lose sight of their values and goals. At least in the nonprofit and human rights world–why would you run your projects like a corporation? We are literally not-that. When I’m the artist, I appreciate trust and being values-aligned with the folks commissioning me.

What do you want your drawings to do? Educate people? Inspire them? Mobilize them? How?

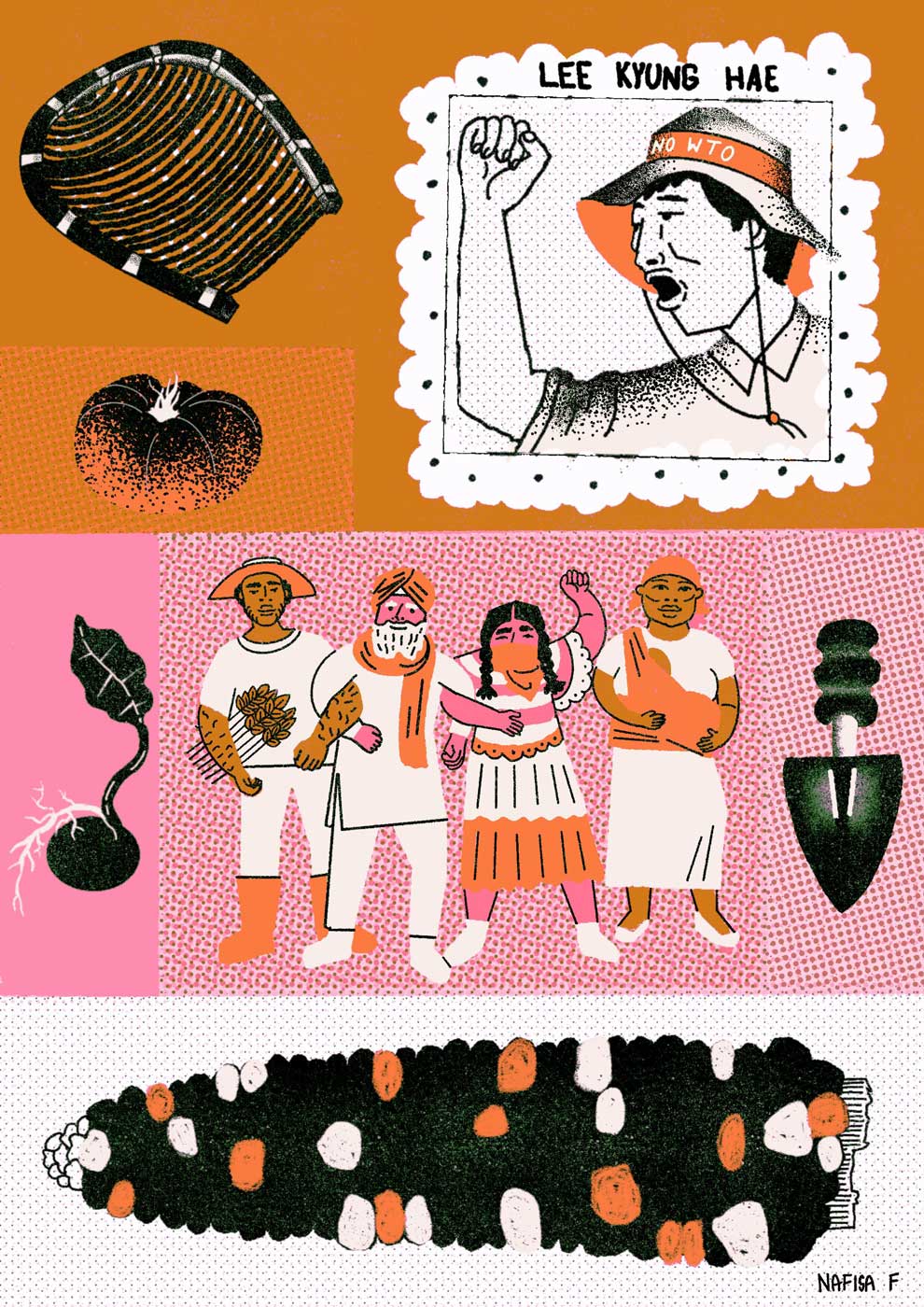

I draw now, but I think I want to become better at creating comics as a tool for political education. Just like Tipu’s Tiger, there are so many ways of learning about stuff that isn’t boring. If you’re in the US, our education and political systems are built in a way where we aren’t encouraged to address or learn about oppression or systemic violence. The US continues to enact violence on our own people, but also outside our borders through war, occupation, policies, and economics disguised as “development aid” or support. I spent a good chunk of my life learning in school and in social movement spaces about alternative ways of living and about people-powered systems of care and liberation. I would love to eventually be able to draw some of these political stories as comics or more narrative things.

What living artists inspire you? What dead artists?

I love artists who have a sense of humor but also have searing political critiques about the world. The performance artist, Patty Chang for example can distill such complex ideas and feelings into such tight projects. Like her 2001 video “In Love” is a looped video played in reverse of her eating an onion with her mother, then father. In reverse it looks like parent and child are kissing and crying, and slowly regurgitating an onion. Like, what?? This video is about intergenerational trauma as a woman of color and the inability to communicate across generations—but with an onion. Then there’s Michael Soi, who is a Kenyan painter known for his boldly colored acrylics depicting hyper contemporary politics on questions around extractive economics, race, gender, and exploitation in East Africa. His paintings might make people uncomfortable but their directness isn’t didactic—they just make the viewers think and ask a lot of questions.

As for dead artists, I never studied art so I don’t know that many. I have a crush on the queer, Hungarian-Indian, modernist, painter Amrita Sher-Gil, though. She has a great painting called “Self Portrait as a Tahitian” which is a response to the French painter Paul Gauguin – who drew objectified, sexualized, paintings of young “exotic” / “primitive” French-Polynesian women. In Amrita’s version she’s also nude, her eyes are not passive but glaring, and there is this giant shadow of a European man looming behind her. Her complex and defiant stance is an assertion of personhood that resists sexualization and objectification, and a direct response to a white male colonizer’s gaze (the shadow). Pretty punk.

Interview conducted via email in May, 2023.

Signal: A Journal of International Political Graphics & Culture is the collective project of Josh MacPhee and Alec Dunn. All copies of Signal are available for sale here on Justseeds. You can find all of our previous Dispatches here.