This is the seventh edition of Signal: Dispatches, an ongoing short interview series with political artists working around the world. One issue of Signal: An International Journal of Political Graphics & Culture takes about a year to get from seed to printed book, so we are taking the opportunity here to throw a quick spotlight on people making great things and organizing, right now. This month finds us in discussion with Hollie Moly, a brilliant and hard working political artist, designer, and printmaker who lives in Melbourne, Australia.

You can find all of the previous Dispatches here.

Will you tell us a little about yourself? Who are you? Where do you live?

I just want to start off by saying how thrilled I am to be included among the artists featured on this blog series already. I’ve been following the project for a little while already, because I think it’s important to get an insight into the process and motivations of artists working in social movements around the world. Too often art making is treated as a competitive pursuit, celebrating the individual genius of some great artist — but none of us are creating work in isolation. I think making art is an inherently collaborative process, and the best art is born out of the inspiration and ideas we draw on from the people, the movements, and the work that we’re immersed in. I’ve found it really useful to hear from the artists already featured, and I’m glad I can throw some of my own ideas and process into the mix — hopefully other people may get something out of that too.

So I’m Hollie, I’m in my late twenties, and I live and work on unceded Wurundjeri land in Melbourne, Australia. I’m a nursing student, and have worked in hospitality for the last 10 or so years, mainly in cafés and bars. I reckon I can trace my path into illustration back to one of my first café jobs, when I was working in hospo in Germany. I was asked to draw the specials board for the day, figured I’d do a good job of it, and somehow ended up getting into the University of Arts in Berlin with what was mostly a portfolio of chalkboards. I studied there for a couple of years and did some freelance illustration work while bartending, but in the process I completely fell out of love with drawing (and fell asleep in class a lot). People say you should find a job doing something you love, but the whole process just left me feeling alienated and insecure about my work. I didn’t pick up a pencil again for years until I moved to Melbourne and started studying my other lifelong interest — history. I wasn’t really a consciously political person up until this point, but I think we can all see that there is a lot of injustice around us. I was determined to understand why the world is the way it is (i.e. pretty fucked up). For me personally, it was probably my experience of working in an industry rife with wage theft and sexual harassment and the political inertia around the existential threat of climate change that were radicalising. Then you start reflecting on your own experience of exploitation and oppression — as a worker, as a woman — and it really opens your eyes to the blatant racism that is inherent in Australian society, the oppression of the LGBTQ community, the plight of refugees. Then you have a lot of thoughtful discussions with political people around you and you decide it’s not enough to describe the oppression and injustice that you’re looking at, you need to do something to change it. Then you’re like oh shit, I think I’m a socialist.

I got involved in my union, and pretty early on we decided to march in as a little contingent to one of the climate rallies called by Greta Thunberg. Everyone brings a homemade sign to the climate rallies, so I thought, right — I can knock one of those up too. I sat down, sketched a little design based on an old lino cut by Franz Seiwert, then got really shy and ended up making a little cardboard sign that would have been smaller than A4. I had this tiny sign clutched half hidden in my hand most of the day, until a comrade from one of the socialist groups took one look at it, told me it was brilliant and that they would have loved to get it printed on a t shirt.

The next sign I made was slightly larger, we’re talking at least A4 now. I’d been taking a really keen interest in protest movements internationally, and International Women’s Day seemed like the right moment to take the wonderful May ’68 slogan “Beauty is in the Street” and celebrate the women on the frontlines of struggle. I drew a simple sign featuring some of the women I’d seen in images coming out of Sudan, Chile, India and Lebanon. I brought it along and a contingent of Sudanese women at the protest called me over to take some photos, thrilled to have spotted the iconic Alaa Salah on it. Little moments like that, you just feel how interconnected our struggles are, and how even a scrap of cardboard that I made can express something to other people that I couldn’t otherwise put into words. I’m incredibly grateful to the many comrades around me that have made invaluable interventions into my political education, and hopefully making art for the movement is my way of paying that generosity forwards. Having something important to express has been the key to building my own confidence and skills. There’s no better feeling than having someone look at your art and say, “Exactly, that’s what I’ve been trying to say this whole time!”

The most important thing I can stress is that artistic talent is totally overrated. I think it undermines the work and effort that the gifted artists around me put into their practice — and scares the shit out of those of us who doubt our own abilities. If you’re curious about making art, just give it a go. It can be exhausting, but mostly it’s a lot of fun, and really satisfying. The working class is the most creative, productive force in society after all.

You have a great design sense- allowing in many elements and lots of feeling of motion/action without feeling cluttered. How do you do it?

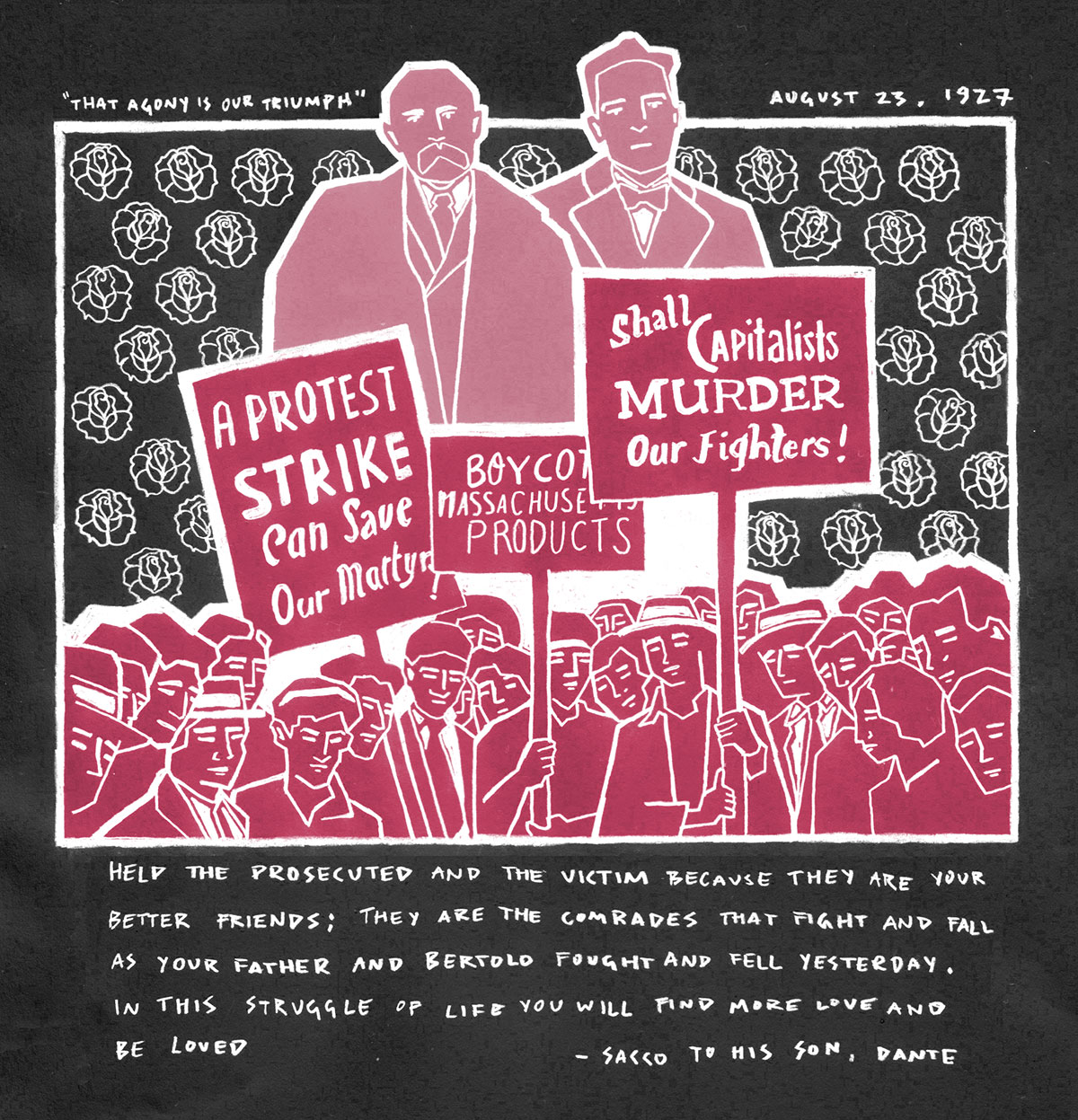

The most time consuming part of my process is definitely research — a habit I picked up while I was studying history. I’m always on the look out for great graphics — mostly in archives, books and journals, but also on the walls of the labour institutions in our city, in the streets, on social media… basically wherever I can find them. I consciously draw on this work to create my own, because I consider the liberation movements of the past to be integral to the ones I am participating in today. In particular, I think that a lot of key lessons have already been learnt in the process of struggle — we’re certainly not the first people to try and form unions in our workplaces, to try and organise mass movements against war, to build a boycott against an unjust regime — but we need to make sure that the hard-earned lessons of the past aren’t forgotten, or we’ll just end up making the same mistakes again. So I look not only to the ideas forged in struggle, but to the imagery — to try and draw out those continuous threads that link us all together. I like to find photographs, archival images of protests and strikes — and of contemporary struggles of course. I usually get a bit emotional looking through them, the bravery and humanity that shines through in those images… I think that’s where the movement in my own work comes from, because I’m trying to capture that moment of action, where ordinary people rise up in defiance against the injustice that grinds us all down. And finding the right emphasis for a piece is really important to make that point clearly. I also like to read a lot, and when I’m responding to something unfolding in front of us, I always try to discuss it with my comrades, and to find out what the people involved are saying about it, until I’ve narrowed down the message of a piece. It’s that process of research, and of refinement, that I think is probably the strength of my work rather than any kind of technical ability. I think I’m most successful when the piece is easily understood at one glance, but I also always try to incorporate broader ideas about our movement’s history, about solidarity, and about internationalism into the details. I want to tell a story about the way forward with each piece.

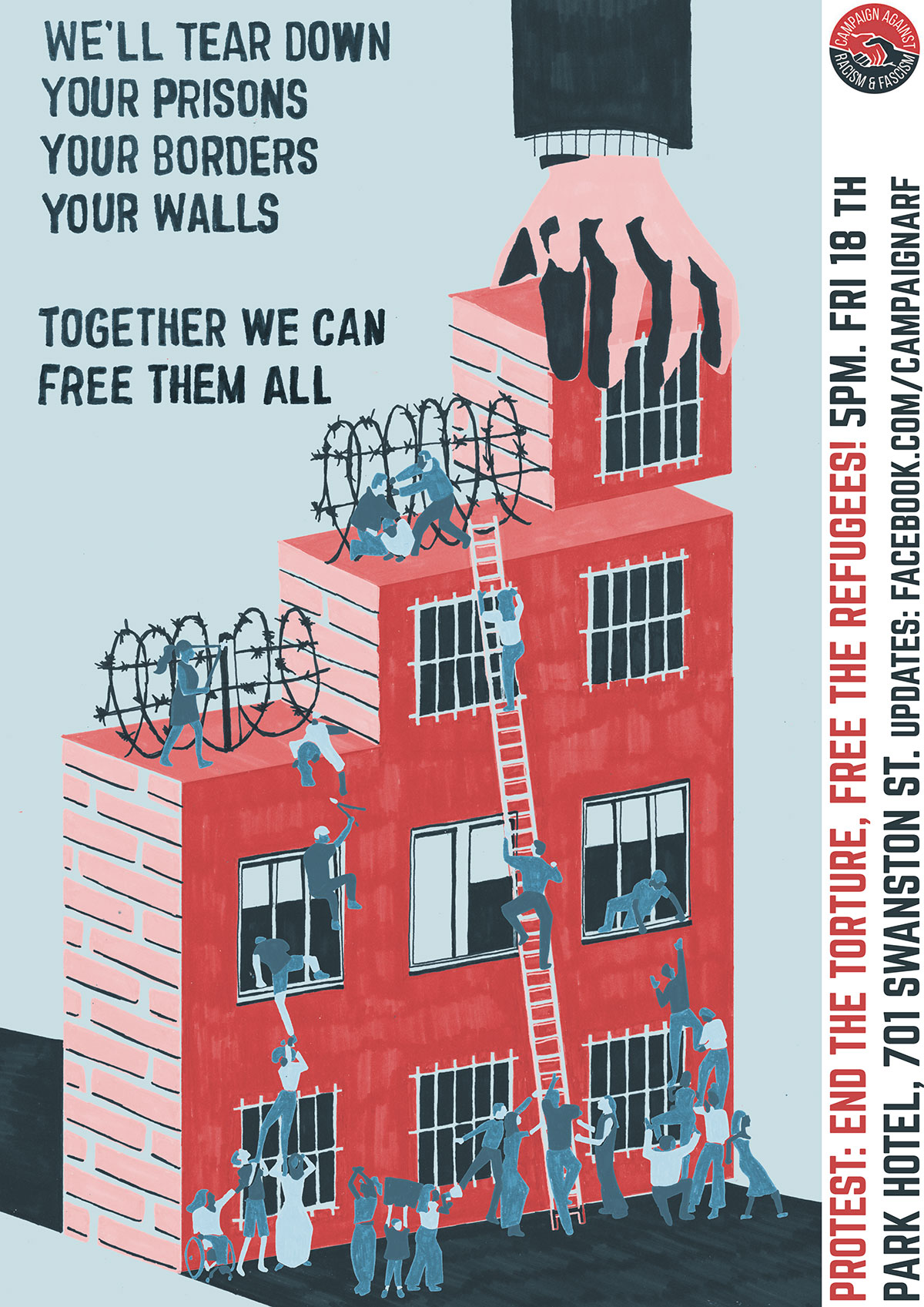

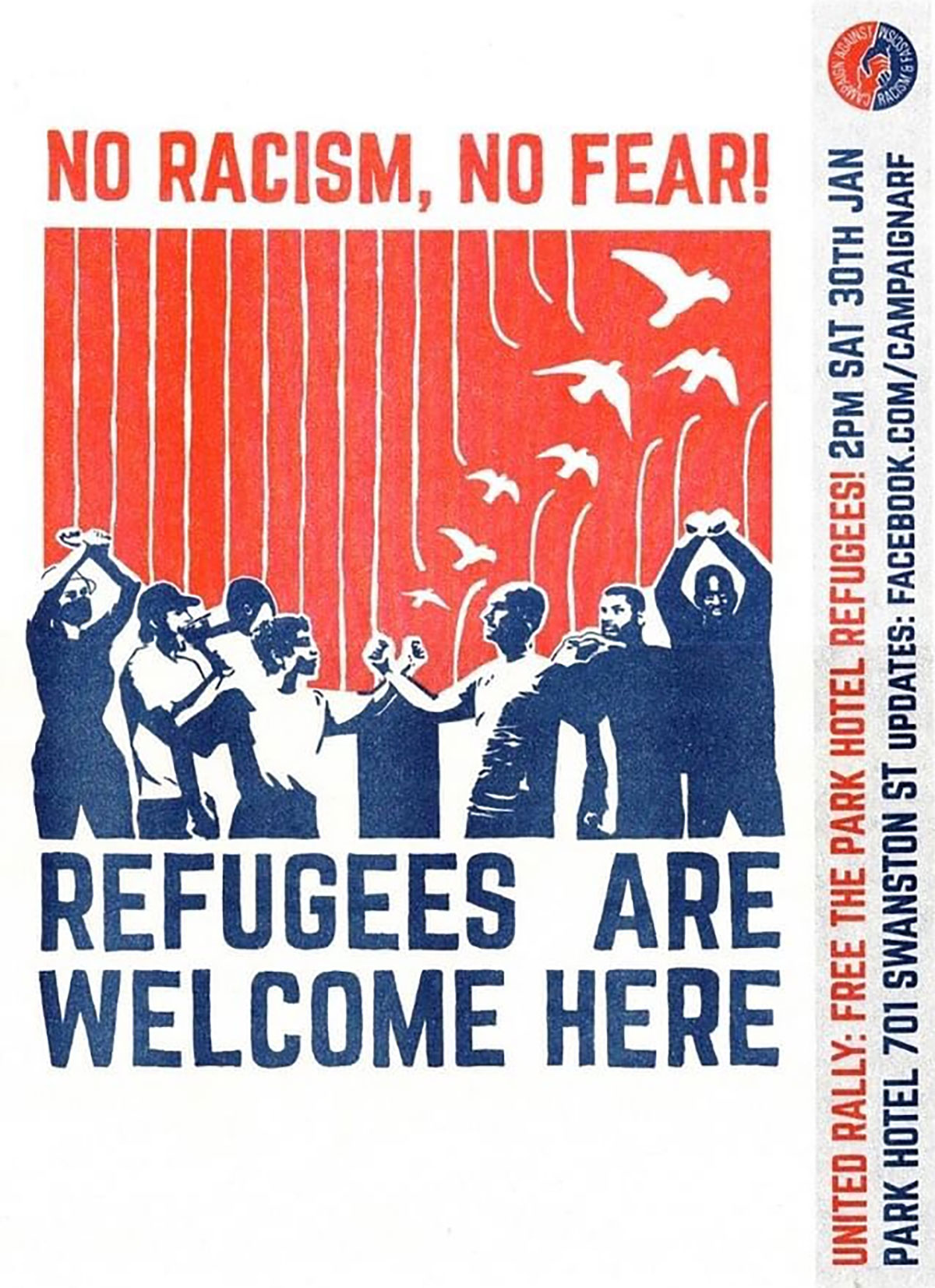

Can we walk through one of your pieces, ‘Together We Can Free Them All’? What was this made for? How did you choose the images/subjects? What is your process like?

The “Together We Can Free Them All” poster came out of my involvement with refugee campaigns in my city, along with another poster, “Refugees are Welcome Here”. The Australian government is pretty infamous for the cruelty and inhumanity of its refugee policy. Basically, our government has enacted countless cruel policies to “deter” would-be asylum seekers, including torturing people fleeing danger and violence and keeping them in offshore camps. I think it was in late 2019 that they introduced some short-lived laws that brought about 60 refugees over from the camps for medical treatment, then immediately scrapped them, leaving these men in limbo. Some of them had been locked up for seven years already, and now they were locked in a small hotel room.

We’d go to protests at these big hotels, and stare up at the windows, and you could literally see the men waving back at you (until they added a dark tint to the windows so they couldn’t be seen by the protestors outside). I can’t really express what it was like to be looking into the eyes of these men, and to only be able to wave back. Seeing refugees quietly locked up in hotels in the middle of Melbourne, it can make you feel totally powerless. But it’s not like these policies are actually enacted in the interest of — nor with the active support of — the great majority of ordinary people here. We know governments go after the most vulnerable people as scapegoats and as political footballs because they think they can get away with it. It’s the very meaning of solidarity that we recognise our own interests lie with those people, and that we must stand together with them not only because it is the right thing to do, but because we are all agents of our own liberation.

I made these pieces because I just needed to do something — anything — in the face of such injustice. But we also used them as the basis for posters promoting protests outside the hotel, and meetings discussing the way forward for the campaign. I was really grateful for the contribution of Bailey and Glom Press, a worker-run printing co-op based here in Melbourne, who kindly donated a bunch of riso prints of the posters for the campaign. They came out great, and some of them ended up on walls in the city before the protests, while some them ended up being used to fundraise for the campaign. Pretty cool to have them come out looking so polished considering my process. I drew all of my early work on A4 printer paper, in black permanent marker, scanned them with a slightly scratched scanner bed of a $30 printer, and then just digitally coloured them in a free browser version of photoshop. Sometimes a lack of materials is a constraint, but I reckon sometimes it’s helpful in developing your own aesthetic. I’m experimenting more now with different mediums – I particularly like making lino prints – but I still pull out the Sharpies pretty often when I want to respond to something unfolding quickly in front of me.

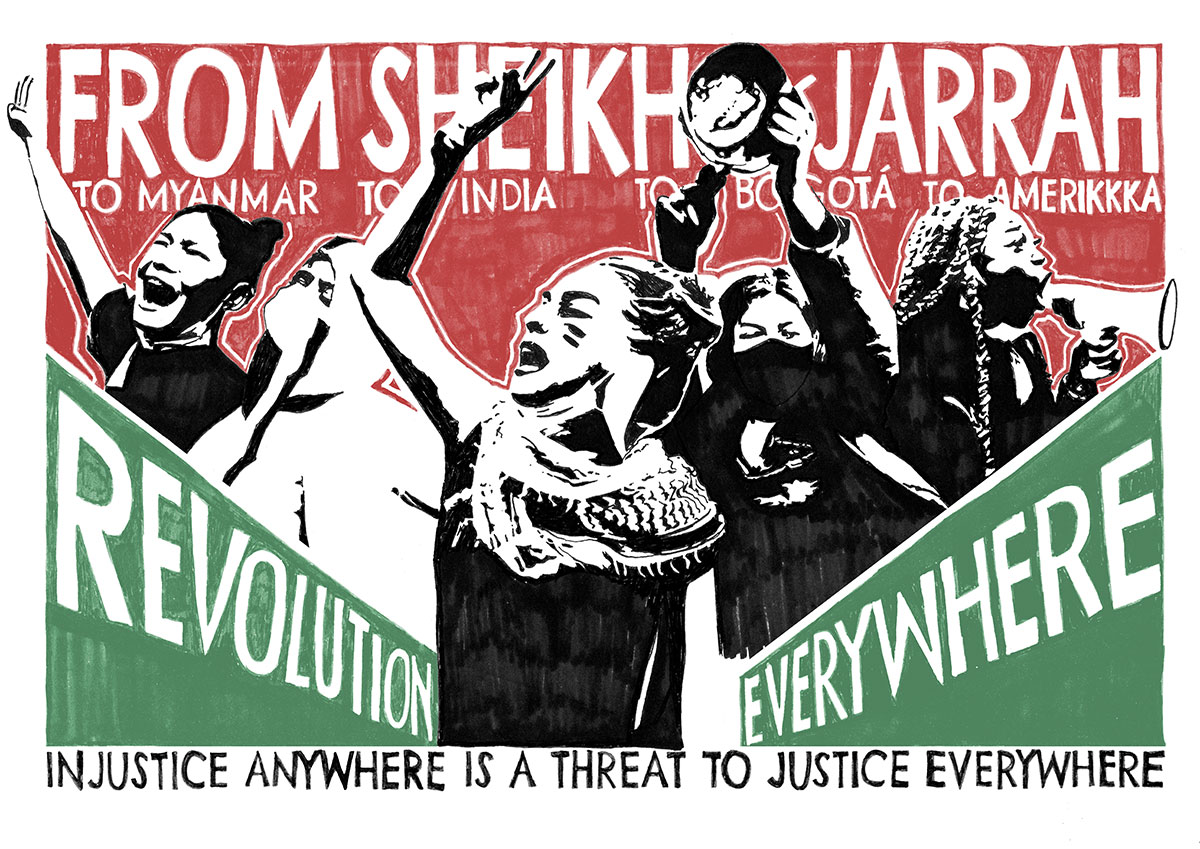

I love the concept behind the year-end 2020 zine and poster project, both showing specific locations of actions and also drawing on larger ideas of interconnectedness and global solidarity. How did this project come about? What did you do with this?

I loved making this zine! It was such a big year of struggle internationally, there were public socialist meetings every other week discussing the newest developments in different parts of the world. In particular, I can remember thinking that the spread of the Black Lives Matter movement across the world really encapsulated the potential of struggle to burst across borders. We live in such a shitty world, that I think it’s important to take a moment to record and celebrate struggle. So I decided I wanted to express my solidarity with those that dare to struggle, whether in Thailand or Lebanon, the USA or Poland, Iran or Nigeria, Belarus or France. I set about drawing something that would express that kind of internationalism. The concept just popped into my head, and then after a bit of trial and error I started putting it together. Each panel can stand alone as a testament to the movement in a particular country, but unfolded as a poster each movement stands together, alongside the others — because while every struggle exists in its own context, when we look to the bigger picture, those struggles are linked together across borders as a part of the fight for a better world. And then I used my comrade’s guide on how to actually make a zine, because I couldn’t work out how to fold it.

It was just a project I did under my own steam, but I posted a little video of the zine to my personal facebook page and I must have got something right, because people really got where I was coming from and wanted to have a copy. A comrade helped me set up a little google form to organise distribution of the print and another friend who volunteers in a left-wing bookstore in the city put a few copies on sale there. I think I also ended up donating some copies to the organisers of the refugee protests I mentioned earlier, Campaign Against Racism and Fascism, to sell at a stall at a socialist conference. I think the coolest thing about making it is that I still get sent photos occasionally, where friends have seen the work pop up in someone’s home, or in a bar. I’m really grateful for that, and the feedback people have given me, it’s really cool when people can identify the influences in your work. I ended up deciding to get onto Instagram because of that zine, which I’d avoided previously cos that shit is stressful.

You have many graphics specific to issues around labor and unions, do you or have you done work with unions in an official capacity and are those relationships ongoing?

Unionism is pretty integral to my politics, both in my own life and in my broader orientation to revolutionary politics, and there is a long tradition of unions supporting the cultural development of working people. I try to be an active union member wherever I work, and I really think that if you have an orientation to mass politics, then you have to meet people where they’re at and build from there— and over here I reckon that is still in our unions, even if the union movement is pretty hobbled and weak at the moment. I usually do the work unofficially — I guess I like to think of it as a rank and file unionist making art for other rank and file unionists. I have done some work officially too though, and it’s really something to see your work hung on a union noticeboard, or put up in a tea room on a union site.

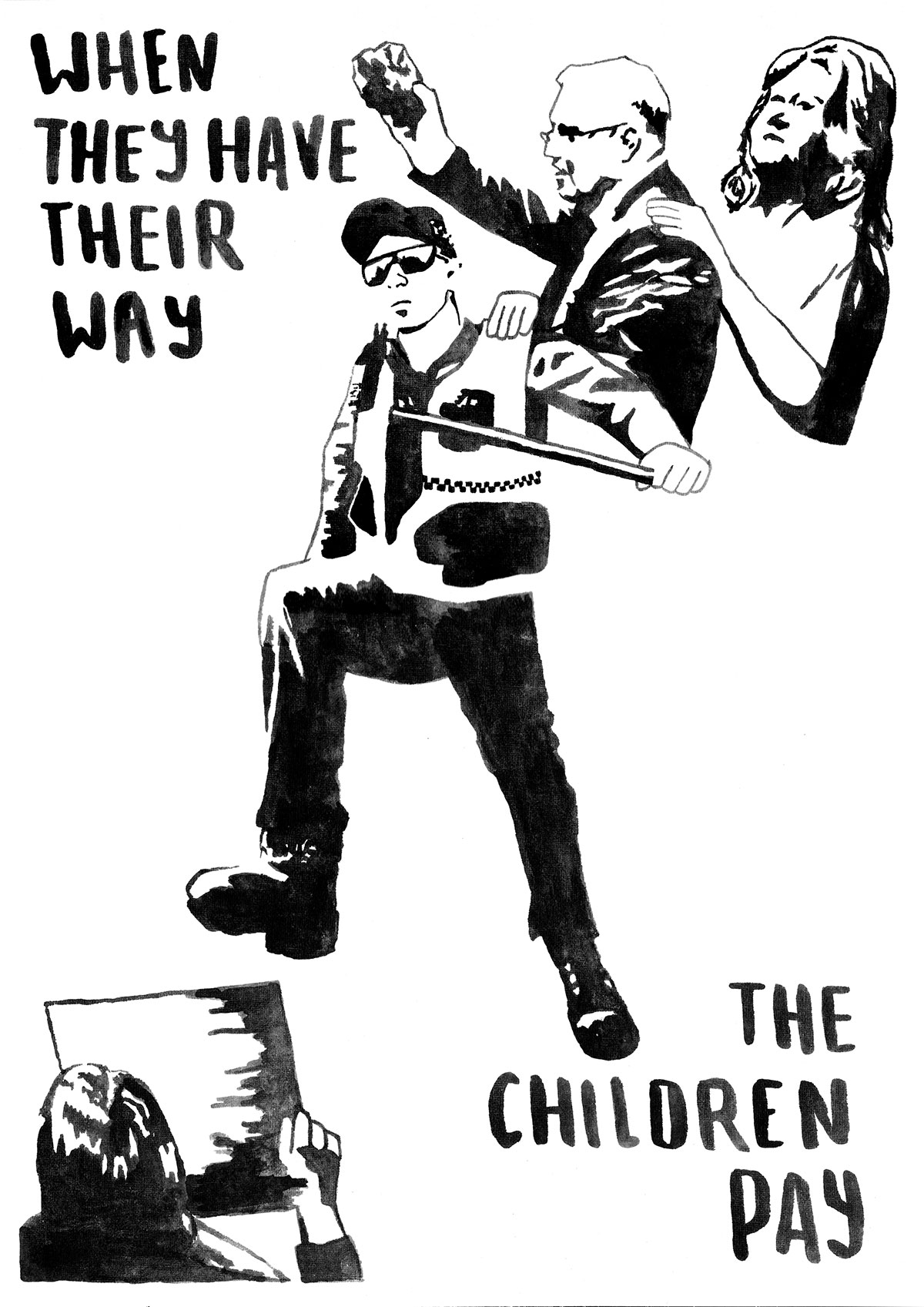

The informal work I’ve done is usually inspired by political cartoons, in particular I love looking through old IWW cartoons. I think the strength of those drawings is that they are (usually) easily understood and the format is versatile enough to respond to the political questions in any given context. It’s really important for me to be able to develop a visual language that means I can respond quickly to unfolding situations, and answer questions that arise without needing people to necessarily have the same political vocabulary that I do — it is the ideas that are the important part after all.

An example of the more official work was that a comrade of mine was involved in this incredible rank and file organising effort in the libraries out in Geelong, an hour or so out of Melbourne. These staunch librarians went out on strike over pay and conditions, and they won. My comrade put me in touch with the union pretty early on to design the t-shirts for their campaign, featuring a slogan voted on by the librarians. The pictures of the librarians out on strike in those t shirts.. just amazing. Talking to the librarians about the design, and their experience of industrial action? Even better.

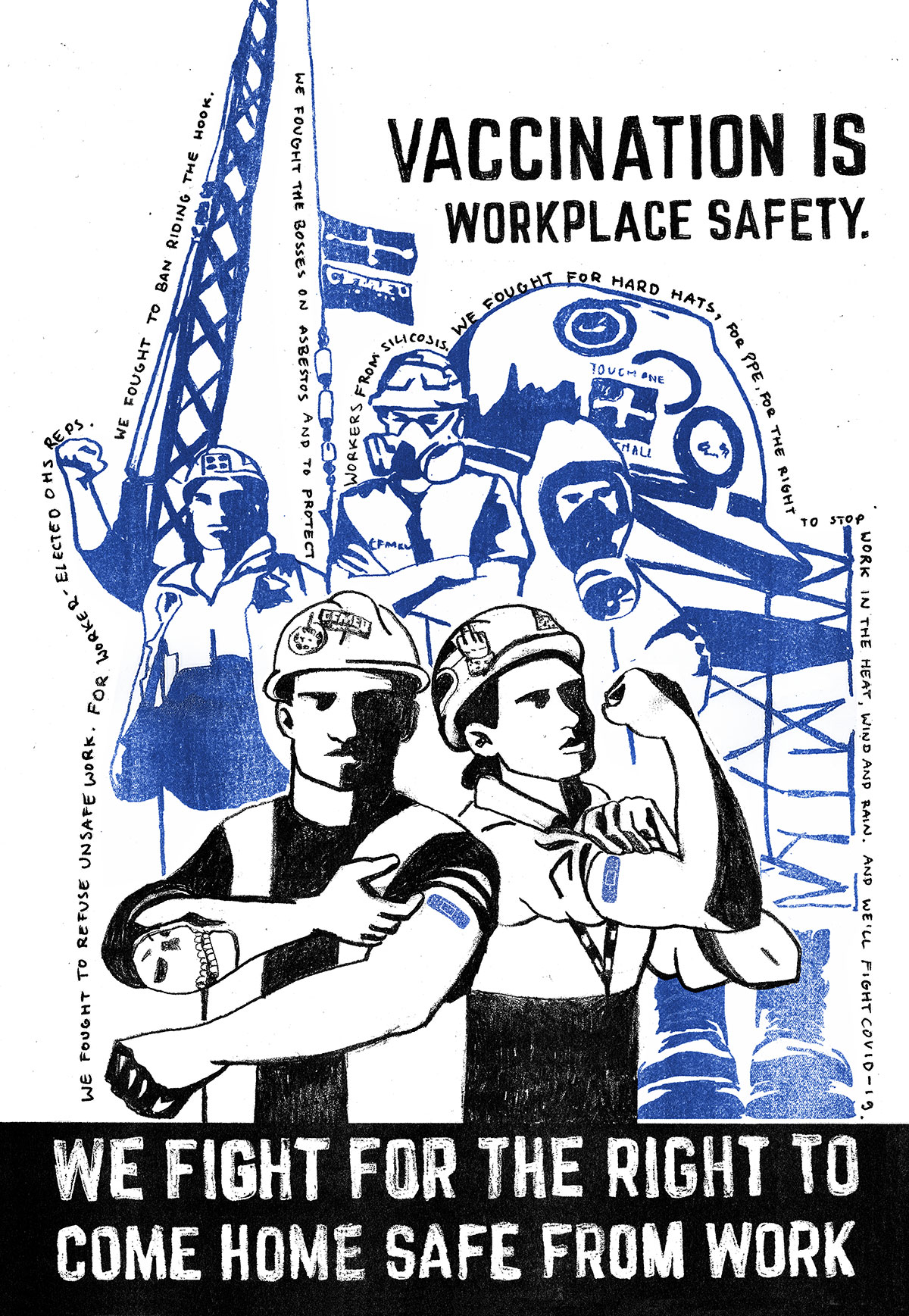

Then there was another time I made a pro-vaccination poster in response to the anti-vax protests that smashed the windows of the construction union’s office at the height of the pandemic over here. I had unions in Germany and in Canada writing to me to get copies of the poster, and a branch of the construction union reached out to me to get the posters printed for their sites. I was really glad to make a useful contribution to the conversation about vaccination, particularly given the influence of the far-right on the antivax movement.

I focus a lot on labour issues because I’m a proud unionist, and so it’s important to me to be able to not only support the union movement, but to criticise it too. But I always want to be on the side of working people, and that means making art that celebrates working people acting in their own interest, and in the interest of society as a whole. Unions are all about people coming together to take that kind of action — even if parts of the movement seem to have forgotten it. But I think that working people remember even when officials forget — or at least we need to remember if we’re going to get shit done.

Your banners are rad, what’s your banner making process?

Thanks! Banner making is always a special process, because it’s impossible to do alone. Even if you sit up all night painting a banner (and getting paint all over the floor of your rental oops) it’s not like you can carry it by yourself. So the more you work with your comrades, the better. I usually feel a bit shy about proposing a design — a part of me is still thinking about making A4 pieces of cardboard — but with the input from the people who will be carrying the banner, and their effort in realising it, you can feel really confident about doing the artistic equivalent of yelling a slogan through a really loud megaphone.

The anarchist communist tendency that I belong to is pretty small and disparate, but we’re working on building it. Organisation is really key to our politics, and one small part of the process of building that organisation is having a more visible presence at demonstrations. Having a banner to rally around is one small way to make an intervention into the politics of the demo (and also makes finding each other in the crowd easier too lol). I’ve also been lucky enough to work with comrades from other political tendencies to make banners with groups like the Uni Students for Climate Justice, although I am not sure they have forgiven me yet for a slightly too elaborate design for the timeframe we had to paint it (I have learned from that one I promise!).

There’s a wonderful tradition of banner making in the labour movement, so it’s important for me to be a part of keeping that tradition alive. Ultimately, I want to be able to express to the people around me what it is that I think we should be fighting for. Rallies are a great space to get a glimpse of the potential of the masses of people to transform society, to feel less isolated in the face of the alienation we are all experiencing, to take a stand against injustice. But rallies alone will never be enough to build the strength we need to actually change things, so I think it’s important to be consciously political in these spaces.

But if you meant practically speaking, what is my process? Discussing, sketching then scanning the design, sending it round to a few comrades to get their feedback, and making any changes. Then projecting it onto a big piece of fabric I’ve taped to a wall, carefully tracing around the design, then laying out much more newspaper than you think you will need on the floor (or ideally, a big table), inviting your comrades to join you and painting it together. Another inevitable part of the process usually involves my dog walking over the wet paint and adding his own little contribution of paw prints and dog hair to the design. I usually just get calico from a fabric store, and reasonable quality acrylic paint. I have used fabric paint before too, but it’s quite expensive, and only really worth it if it rains a lot. And one more thing I will say — black fabric looks great flying above you in a crowd, but it always takes quite a few coats to make the colours pop. The wonderfully obnoxious pink on our International Working Women’s Day banner was the result of 3 coats of paint. Worth it when women from all parts of the rally were coming past to get a picture of the banner, but you have been warned!

What is important for you to convey in your artwork? What ideas or philosophies is your work built on?

I think I have probably explained this in WAY too much detail already answering the other questions? Can spell it out though, but it’s probably not necessary. Basically I’ve found my way to anarchist communist politics and I’m mostly just out here making art that celebrates building towards socialism from below. I’m probably most influenced theoretically by the work of Malatesta, Marx and Connolly, and by the CNT-FAI and the Mujeres Libres, the IWW, and closer to home, Jack Mundey and the BLF [Builders Labourers Federation]. If I had to pick a few artistic influences, I’d probably go with the work of Franz Seiwert, Käthe Kollwitz, Emory Douglas and the Atelier Populaire, but that is by no means an exhaustive list!

What is Workers’ Art Collective? How is it organized? Will you tell us about the relationship between your work and the work of the collective?

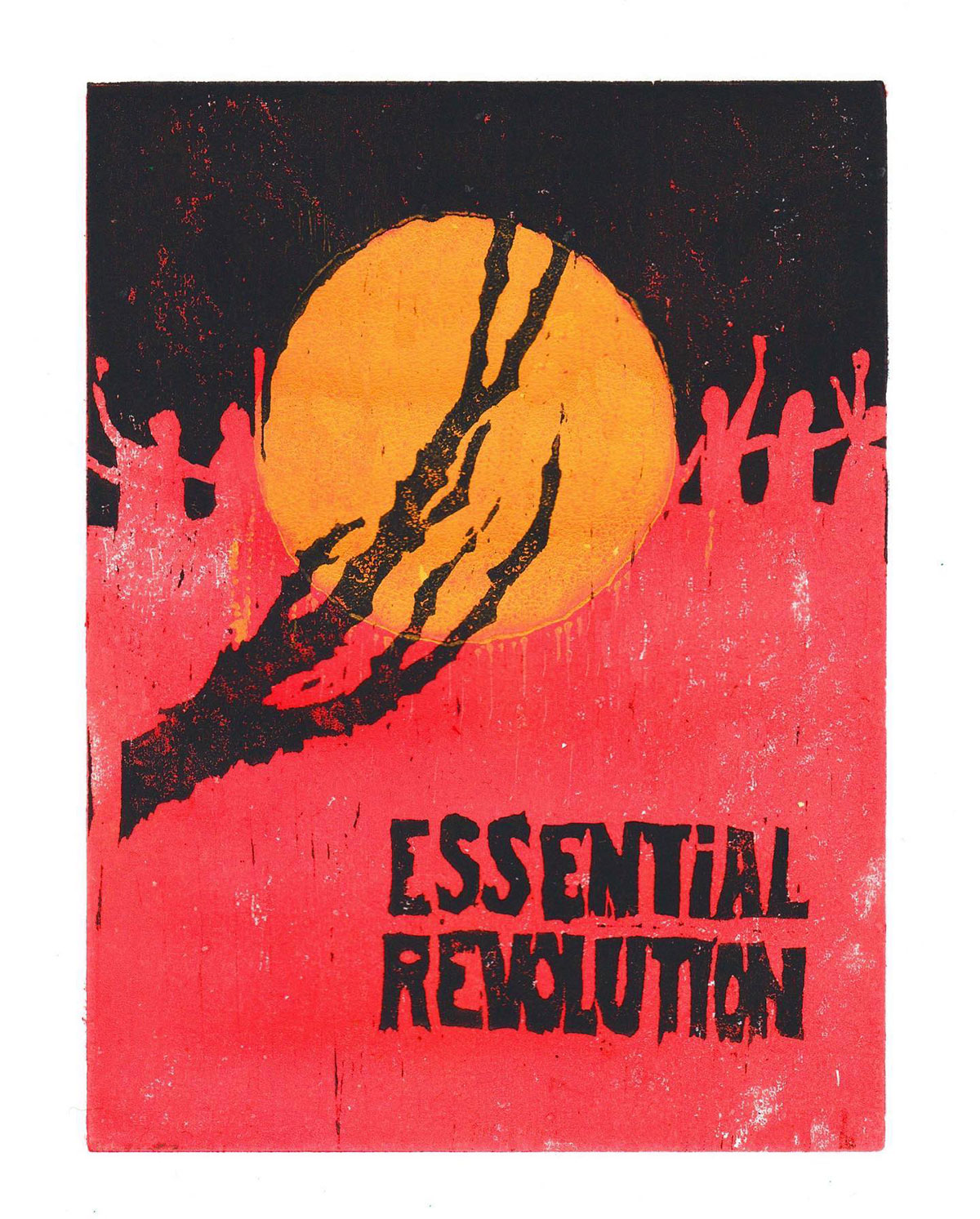

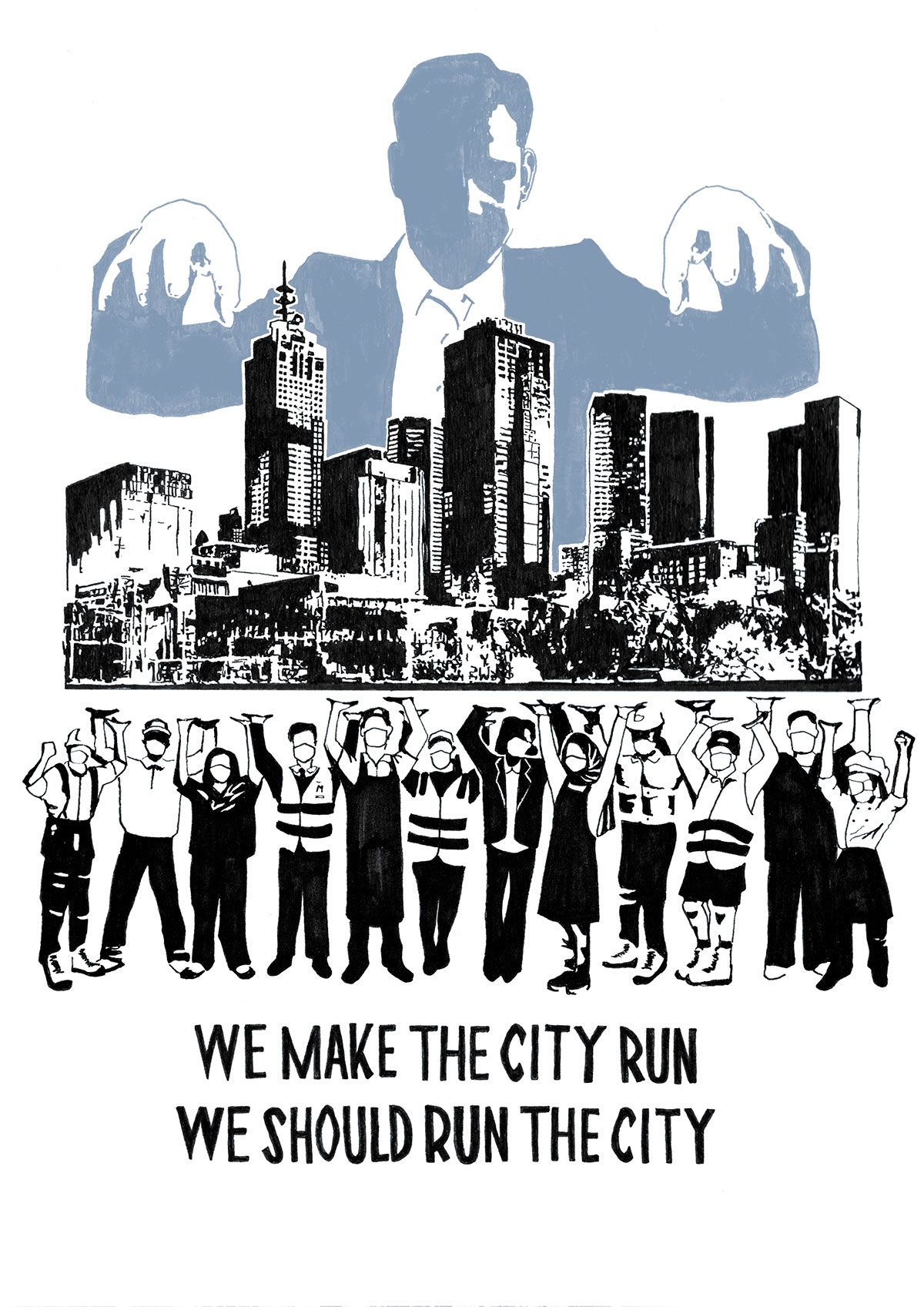

WAC is a collective of artists (illustrators, muralists, street artists, cartoonists, painters, graphic designers, writers) based in Australia that create art and writing for the workers’ movement. We are workers from various industries, including warehousing, call centres, construction, disability support work, hospitality and general labouring — and we all understand the importance of working class organisation. We’re from a few different political tendencies, but we all believe that a globally united working class is the most powerful force in society, and is the primary agent that can bring capitalism to its knees. We carry on a long tradition of art that not only fights for social justice, but immerses itself within the organs of working class power – the mighty trade unions. We’re a pretty small group, based primarily on long-term organising relationships, and I’m not a founding member of the collective, but was invited to join after hanging around the other artists as an activist. Most of us work out of a shared art studio, and we collaborate on projects, share knowledge, resources and feedback, and get involved in social movements together — whether that means running banner and sign painting workshops, turning up at a picket line, or writing about the campaigns we’re involved in.

We want to develop the collective to open things up a bit more in the future, probably do some more community oriented projects, and I think it’s got great potential. Personally I’ve already gotten so much out of working with the other artists. It’s been great for developing my skills, but even more so for developing my confidence, and interrupting this weird competitive and comparative thing that seems inevitable in the arts. If I had to try and describe what it’s like to be in the collective, I’d say it’s the feeling you get when you spend all day working on something, you’ve completely lost perspective and have got no idea if you’re talking out your arse, or if anyone cares, and then you get a little notification on your phone and it turns out that four other people in the collective have been doing the same thing and have all made these beautiful, distinct pieces of work that are going to speak to different audiences, from different perspectives. You don’t feel like you have to compare yourself to them, you just feel proud that we’re out there together yelling into what can sometimes feel like a void. I get so proud when I see the work of my comrades being used by the unions, or in the media, or out on the streets of Melbourne. You think wow I’m part of something bigger than me, and isn’t the essence of our politics after all? That shit brings a tear to your eye!

How do you get your work out there?

I guess I started with signs at protests, and I’m still doing that in a way by working on protest banners. I also share my work through the union movement, including my own union, and through posters and flyers for grassroots movements. I’ve also recently gotten really interested in paste ups and street art— I did this uni course on art and education and somehow ended up actually pasting up my final project in the street (thanks in part to some advice from a couple of comrades in the collective). I love the idea of putting your work out there into the streets, whether through posters or street art. Advertising invades public space everywhere, but the streets really belong to us. A friend of mine has also started a little distro press, so I’m looking forward to making a few stickers and badges as well. I love seeing agit prop around (especially when it’s covering up fascist propaganda) so I’m glad to have the chance to add to that library.

And of course I share my work through social media. There are probably a few disadvantages to this — mostly the crippling anxiety lol — but I do appreciate getting instant feedback on the work, and the potential to share it easily internationally.

Are you working on any projects right now that you are excited about and want to share?

Oh yes actually! I’ve entered this competition organised by the Maritime Union of Australia to celebrate their 150th anniversary. I enjoyed the whole process, getting into the history of a union that has a proud history of putting solidarity in action to fight for a better world. The deadline was extended and entries don’t close until the 31st March 2022, so it’s the perfect opportunity for anyone reading this to give it a crack as well. You could be an experienced illustrator and an expert on labour history and enter, but you really don’t have to be. You just have to know which side you’re on. The more entries, the better, plus the whole process is pretty fun if my experience is anything to go by.

Are there any artists from Australia that have inspired you, that everyone should know about?

You know when somebody asks you what kind of music you’re into, and suddenly you can’t think of a single band? Well I am certain that the minute I send this email I will have a list of artists as long as my arm that I wish I had included.

I love the work of Wiradjuri, Ngiyampaa woman Charlotte Allingham (@coffinbirth). There’s a proud tradition of both Indigenous resistance and Indigenous art over here, and I think the work she is doing brings those traditions together in a really powerful way. (And as an aside, her work looks so effortlessly cool, which is pretty unfathomable for someone as cringely awkward and earnest as me). A by no means exhaustive list of some other cool, active lefty women based in Australia with Instagram accounts includes Sage Jupe (@jupe.ey), Judy Kuo (@judyk__), Carla Scotto (@carladrawz), and Maddie (@maddiehah).

And obviously I can’t go past the work of my comrades in the Workers Art Collective (@workersartcollective). Before I was a member, I used to obsessively follow their work… and then I got to meet my heroes (and turns out that can actually go really well after all). I think there is a lot of diversity in our work, but a common purpose, and that’s what makes it so successful. In particular I want to thank Sam Wallman (@ourmembersbeunlimited), for his many important contributions to the workers’ movement, but also for the time and effort he puts into fostering the growth and success of other artists around him. You can get a sense for the work of my other comrades on our website or on their social media. You really need to click through all of their beautiful work because you will not regret it for a moment (@nobailey, @benjuers, @NoLuckLopez, @nickyminus, @nic_robertson_neo, Sam Davis, @tia_kass, @van.nishing, Viktoria Ivanova).

Interview conducted via email in March, 2022.

Signal: A Journal of International Political Graphics & Culture is the collective project of Josh MacPhee and Alec Dunn. All copies of Signal are available for sale here on Justseeds.