When MF DOOM (real name Daniel Dumile) rapped the words “refuse to get tickled by the fickle finger of fate” under the alias Viktor Vaughn on “Ode to Road Rage,” it doubled for how he was seen by fans. To them, he was an immortal prophet: a mysterious, masked supervillain who operated from the shadows and could drop mind-bending rap records almost at will. It always felt like MF DOOM was 33 steps ahead of everyone else — including the specter of death itself.

The mythology that Dumile cultivated and the intensely private way he lived his life, led to many of his fans asking how did MF DOOM die when news of his passing was revealed in December 2020. Dumile died while living in Leeds, England, after receiving treatment for angioedema (a sudden swelling often caused by an allergic reaction) at the Northern city’s St James’ Hospital. After being treated by National Health Service (NHS) workers with ACE inhibitors to control his high blood pressure, Dumile’s throat, tongue, and lips became dangerously swollen. By October 21, 2020, Dumile was struggling to breathe and had even forced himself off his own hospital trolley. This resulted in a collapse and being put on a ventilator, where he later suffered from a fatal respiratory arrest on Halloween night.

At an inquest, it was found there were “missed opportunities” to treat Dumile, while his wife Jasmine compared the rapper’s room at the hospital to “an old storage room.” She said there was a two-hour delay in giving Dumile (who had various other underlying health issues) treatment for throat swelling, and claimed his help buzzer had been intentionally placed out of reach. This resulted in distress calls from the 49-year-old rapper to both his wife (who couldn’t be at his side due to COVID-19 restrictions) and the hospital itself, where he hopelessly begged a phone operator sitting in the same building to send over some nurses.

Following the inquest, the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust issued a rare public apology. “I would like to offer our sincere condolences to Daniel’s family, friends and fans at this difficult time,” said the organization’s chief medical officer, Dr. Hamish McLure. “I apologize that the care he received was not to the standard we would expect.”

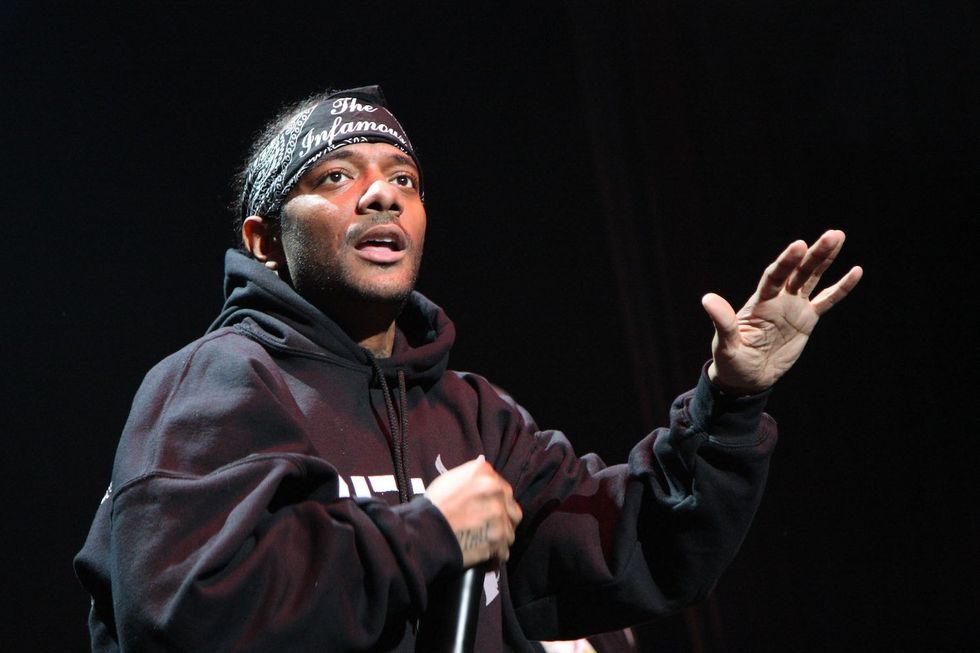

MF Doom performs live on stage during the first day of the ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror’ festival, curated By Portishead & ATP, at Alexandra Palace on July 23, 2011 in London, United Kingdom.Photo by Jim Dyson/Redferns.

An “alarming” trend

For Walasia “MJ” Shabazz, a friend, A&R, and former manager of MF DOOM’s, the way these details have been plastered across the internet has been particularly difficult to take in.

“He was a private person, so it is off kilter to see his likeness, name and image used for ‘headlines’ or in publications like TMZ,” she said. “For myself, as well as the friends and family I’ve talked this over with, we all feel a great sadness, and that we almost have to start the grieving process all over again.”

Rather than be treated in isolation, though, Shabazz said Dumile’s death should be seen as part of a wider trend. One where Black rappers keep on passing away in Western hospitals due to suspect levels of care.

“From Prodigy [of Mobb Deep] to Baba Zumbi [of Zion I], there have been a number of these situations, all with alarming similarities,” she said.

Prodigy died at just 42 after receiving treatment for sickle cell anemia (inflamed by dry conditions of performing live in the desert) at Spring Valley Medical Center in Las Vegas in June 2017. The coroner confirmed he died from “accidental choking” on an egg, which the legendary Queensbridge emcee was too weak to swallow. But it never stated why the rapper hadn’t been supervised while eating it, something you’d have expected given the way his condition impacted breathing.

Zumbi, meanwhile, died at the Alta Bates Hospital in Oakland, California, after staff restrained him during an altercation. On August 13, 2021, the Alta Bates’ staff claimed an incident occurred due to the artist having a “psychotic episode,” resulting in the rapper dead at 49. But for family, friends, and fans this seemed out of character, making it hard to comprehend how someone renowned for their peaceful personality could be killed in an alleged fight with the same staff supposed to be actively helping him. His sudden death has been steeped in mystery and remains an “unsolved homicide,” with his mother Garloyn Gaines pledging that she was “dedicated to seeking justice for his killing” in a statement.

“My most personal memory of Zumbi was when he wrote ‘Sorry,’ because the way he communicated his personal pain about his parents’ divorce was genius,” Amp Live, the late rapper’s Zion I partner, said. “There’s no question that Zumbi was underrated as an MC. It’s just more tragic now because he is gone and can’t fight for his spot.”

Prodigy of Mobb Deep performs at the 2007 J.A.M. Awards and Concert at Hammerstein Ballroom on November 29, 2007 in New York City.Photo by Jason Kempin/WireImage.

Prodigy of Mobb Deep performs at the 2007 J.A.M. Awards and Concert at Hammerstein Ballroom on November 29, 2007 in New York City.Photo by Jason Kempin/WireImage.

A gap in knowledge

The tragic passing of MF DOOM, Prodigy, and Zumbi has been difficult for the hip-hop community to process, with there still being so many unanswered questions around how these rap legends left us. While no one is suggesting that the U.S. or U.K. healthcare systems have a vendetta against rappers specifically, the one thing that seems to link these deaths together is hospital staff unequipped to treat illnesses specifically linked to the Black community.

DOOM, for example, was treated with ACE Inhibitors, which are known to have adverse effects on Black patients. His doctors refused to get “specialist input” about his condition from an immunology expert, seemingly confident enough in their own training. It’s also an established fact that awareness of sickle cell is “low” among medical professionals, with one recent report finding nearly half of its sufferers receive poor care in hospitals. Lastly, according to research by the National Academy of Medicine, Black people experience lower levels of healthcare quality across virtually every therapeutic mental health intervention available in America, while the deaths of Irvo Otieno and Olaseni Lewis have shown a pattern of Black men dying after being restrained with excessive force within U.S. and U.K. hospitals.

“The poor treatment these three men received is tragic and unnecessary,” said Linda Villarosa, the writer behind the bookUnder the Skin: Racism, Inequality, and the Health of a Nation. “Medical treatment and care has long been centered on the experience of white research subjects and white patients, and treatment is marred by the lack of Black researchers. DOOM’s providers should have known, from his records, that the medication he received was not right for him.”

One opinion that has consistently been expressed on social media around DOOM’s death has been the idea that the U.K.’s Conservative government is somehow responsible, with their decades of cuts to the country’s NHS resulting in pandemonium and stretched staff unable to cope with influxes of new inpatients.

“In America, we’re told that Europe has the best health care system and that all people receive treatment because insurance is nationalized, but with DOOM’s recent inquest and the information that’s coming to light, it seems that the lack of care for people of the Afro-diaspora and other persons of color is not in fact any better in the U.K.,” Shabazz said. “That was the most shocking revelation to me. A lot of fans really feel like the NHS killed DOOM.”

Baba Zumbi of the rap group Zion I passed away at age 49 in 2021.Photo by Brian Feinzimer.

Baba Zumbi of the rap group Zion I passed away at age 49 in 2021.Photo by Brian Feinzimer.

The impact of austerity

Joanna Sutton-Klein, an emergency medicine doctor based in Manchester, England, said that the NHS has been put under significant pressure. British austerity has made NHS hospitals a more desperate place: something compounded during the COVID-19 pandemic, where staff were stretched way beyond their pay grades.

“As well as a place of healing, the NHS can often be a place of neglect for patients and this is primarily due to austerity,” Sutton-Klein said. “There is just too much work and far too many targets for staff to process right now, which means patients are left in really undignified situations.”

She shared that when she goes to her day job in Accident and Emergency, there’s often patients slumped on the floor in corridors waiting for treatment, and even old ladies stuck in steel chairs for “significant” amounts of time. “I have treated patients in cupboards and corridors,” Sutton-Klein said. “At the moment, I feel scared about any of my family or friends going to U.K. A&E, as I have no confidence they would receive the medical care they need or would be treated with dignity.

“I definitely think that austerity affects the groups that are already oppressed even more,” she added. “While I cannot comment specifically on DOOM, to me it feels there is an opportunity here for doctors to take more active steps to learn more about treating different populations.”

It is a frank and honest admission from someone on the inside, which gives a unique window into the chaotic scenes DOOM might have found himself in after being admitted to A&E at an NHS hospital. Last year, a review by the NHS Race and Health Observatory published in the British Medical Journal found “overwhelming, stark, widespread, and longstanding inequalities” that people from ethnic minorities in the U.K. experience during their access to healthcare and outcomes. These problems occur at every stage of life — from birth to death — while they are “rooted in experiences of structural, institutional, and interpersonal racism.”

One particularly concerning passage from the report read: “For too many years, the health of ethnic minority people has been negatively impacted by: a lack of appropriate treatment for health problems by the NHS; poor quality or discriminatory treatment from healthcare staff…and delays in, or avoidance of, seeking help for health problems due to fear of racist treatment from NHS healthcare professionals.”

It’s a situation Amp Live believes is mirrored over in America, too, and something he has first-hand experience of.

“The health care system in the U.K. and U.S. needs a big overhaul for all. But I think, like many institutions, it’s always worse for minorities, specifically African Americans,” he said. “After college, I worked in a large county hospital for a few years and saw firsthand how things were going.”

“Health care has just become another means of big business,” he continued. “When you have quotas doctors have to reach or when doctors have to fight insurance companies to get paid for their services, that stress is eventually going to change the attitude of that doctor. In general, you are creating a hostile environment of disgruntled workers in a place where it should be the total opposite.”

A need for change

DOOM’s death has prompted the Leeds teaching hospitals NHS trust to create more training for white staff, so they are more educated on Black conditions or health outcomes (such as the risks of ACE inhibitors). “We have put in place a number of actions, and the wider learning from what happened is to be used as a teaching topic in a number of different clinical specialities,” it said. “We also support the coroner’s recommendation for clearer national guidance and awareness in this area.”

However, for Villarosa, the idea that changes will be implemented fast is unlikely. She advised that even rappers who might feel insulated by wealth and fame, shouldn’t assume they are isolated by racial inconsistencies when entering American and British hospitals.

“In America, the tennis superstar Serena Williams, who is rich, powerful, and famous, had a near-tragic birth outcome when she had her first baby several years ago,” she said. “That showed that wealth and education are not enough to protect Black Americans against poor treatment in our medical system and our society.”

Looking forward, Shabazz said it is now imperative for the hip-hop community to treat DOOM’s death as an opportunity to wake up and treat their health more seriously.

“I think you’d be hard pressed to find, in America at least, an artist who has full coverage to proper health insurance, vision coverage, dental insurance, wellness care, access to holistic treatments and alternative therapies, a flexible spending account, and a good doctor whom they trust if something goes awry with their health,” she said. “These are the core basics that any music executive working for a major label would have access to. Yet, 99.9% of the time the artists signed to those labels? Well, they have no health care to speak of. Until that changes, we’ll continue to see rap artists with GoFundMe pages whenever they fall ill. It’s shameful.”

Amid DOOM’s death, it’s hard not to think about the brilliance of this MC that passed on sooner than many expected. The way he rhymed “fire vocal” with “Eyjafjallajökull” on “Guv’nor” reflected a deep vocabulary and lyrical ability that at times made the artist feel almost superhuman, a testament to how larger than life DOOM was despite being so enigmatic.

If we’re to truly honor the genius of DOOM (as well as Prodigy and Zumbi), the people in the music industry must use the unfortunate circumstances around their deaths to implement serious systemic changes, where non-white patients can be confident that they’ll be properly cared for if they get sick. Agreeing with this sentiment, Shabazz said: “People who make music for a living, regardless of genre, should be provided with health insurance for them and their families. It’s the very least the music industry can do.”

Until then, it’s likely these tragic instances will unfortunately continue to happen, potentially robbing Black artists of a long and healthy life, and fans of an artistry that should’ve been around for much longer.

__

Thomas Hobbs is a freelance culture and music journalist from the UK. His work has appeared in the Guardian, VICE, Financial Times, Dazed, Pitchfork, New Statesman, Little White Lies, The i and Time Out.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web