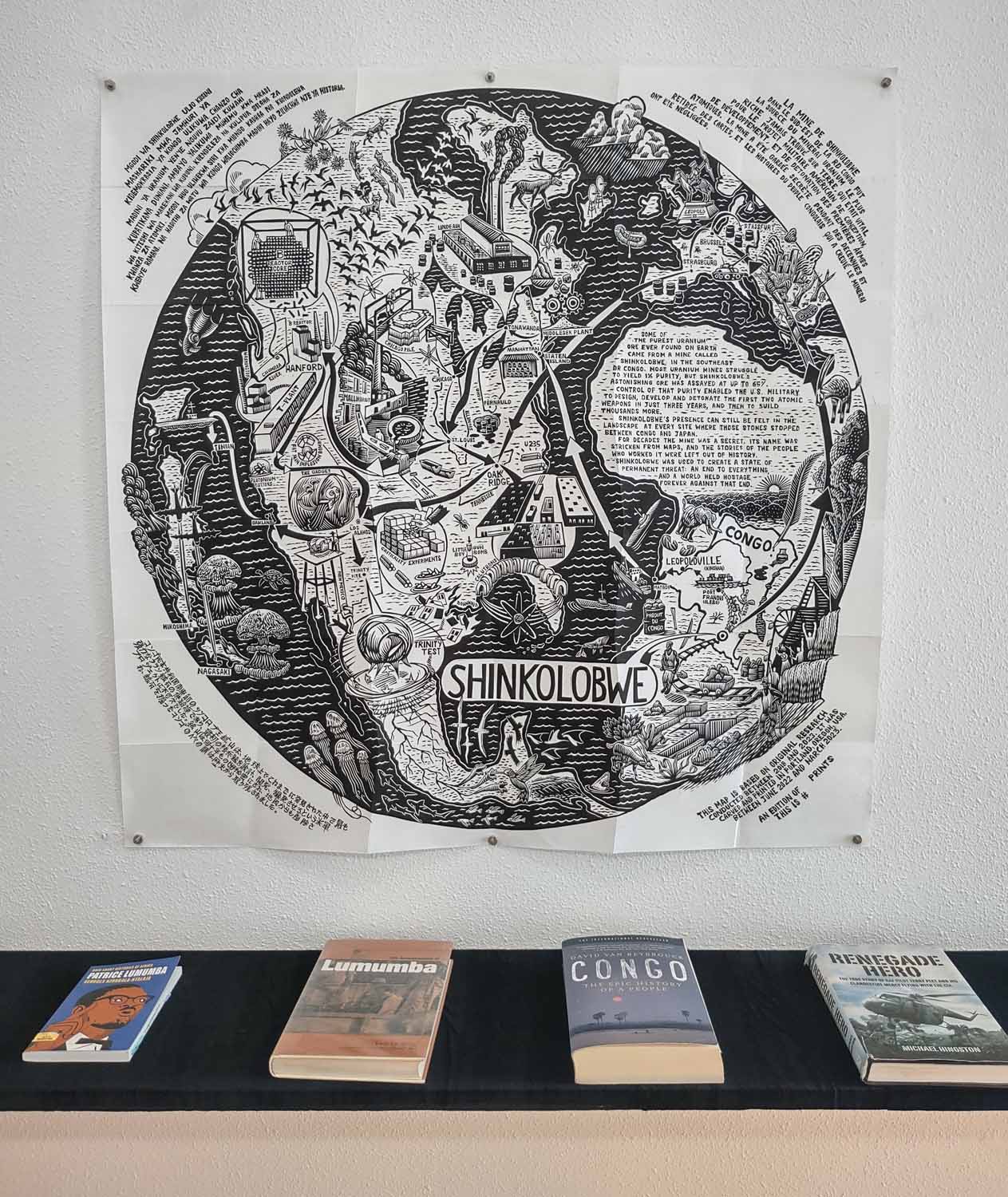

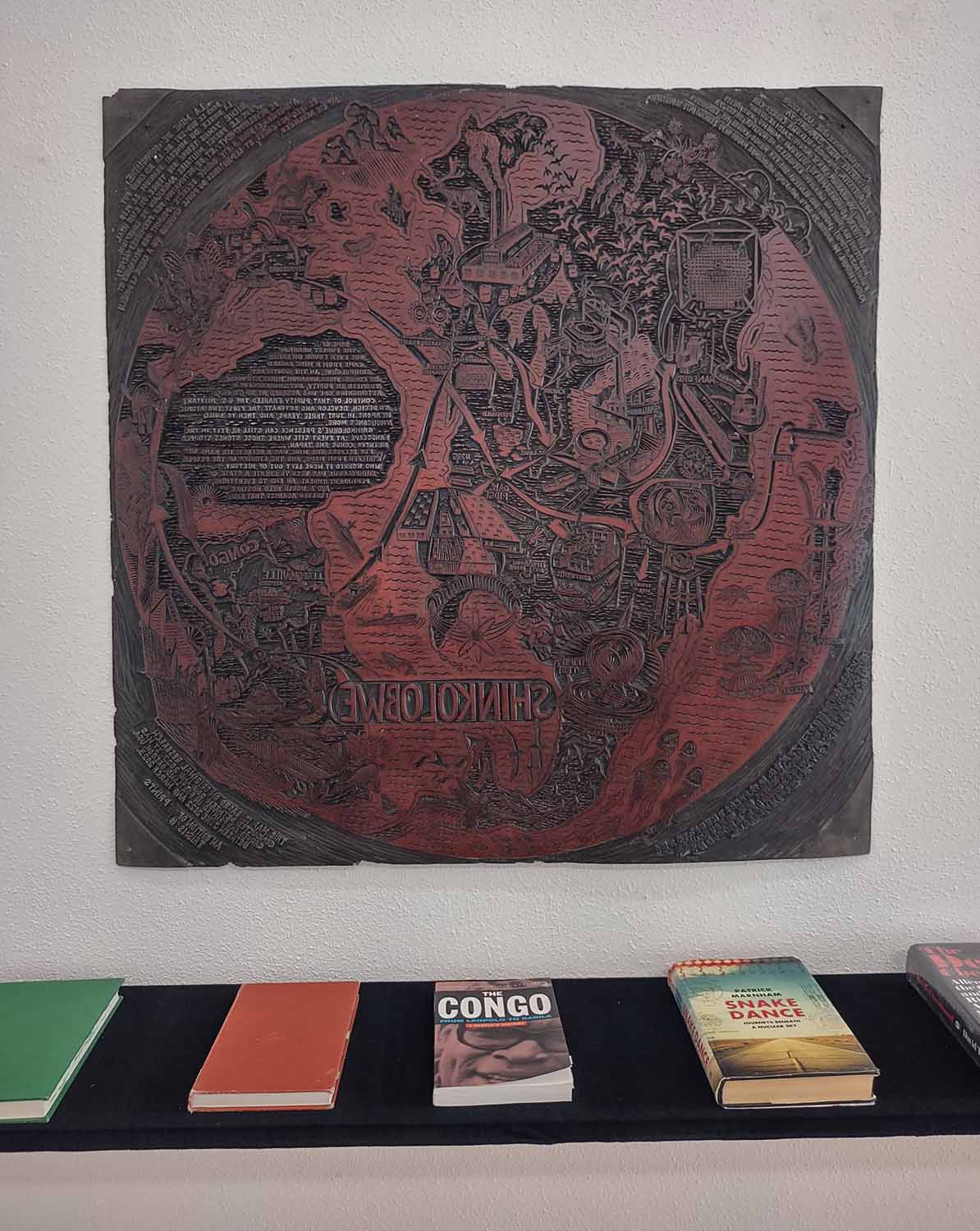

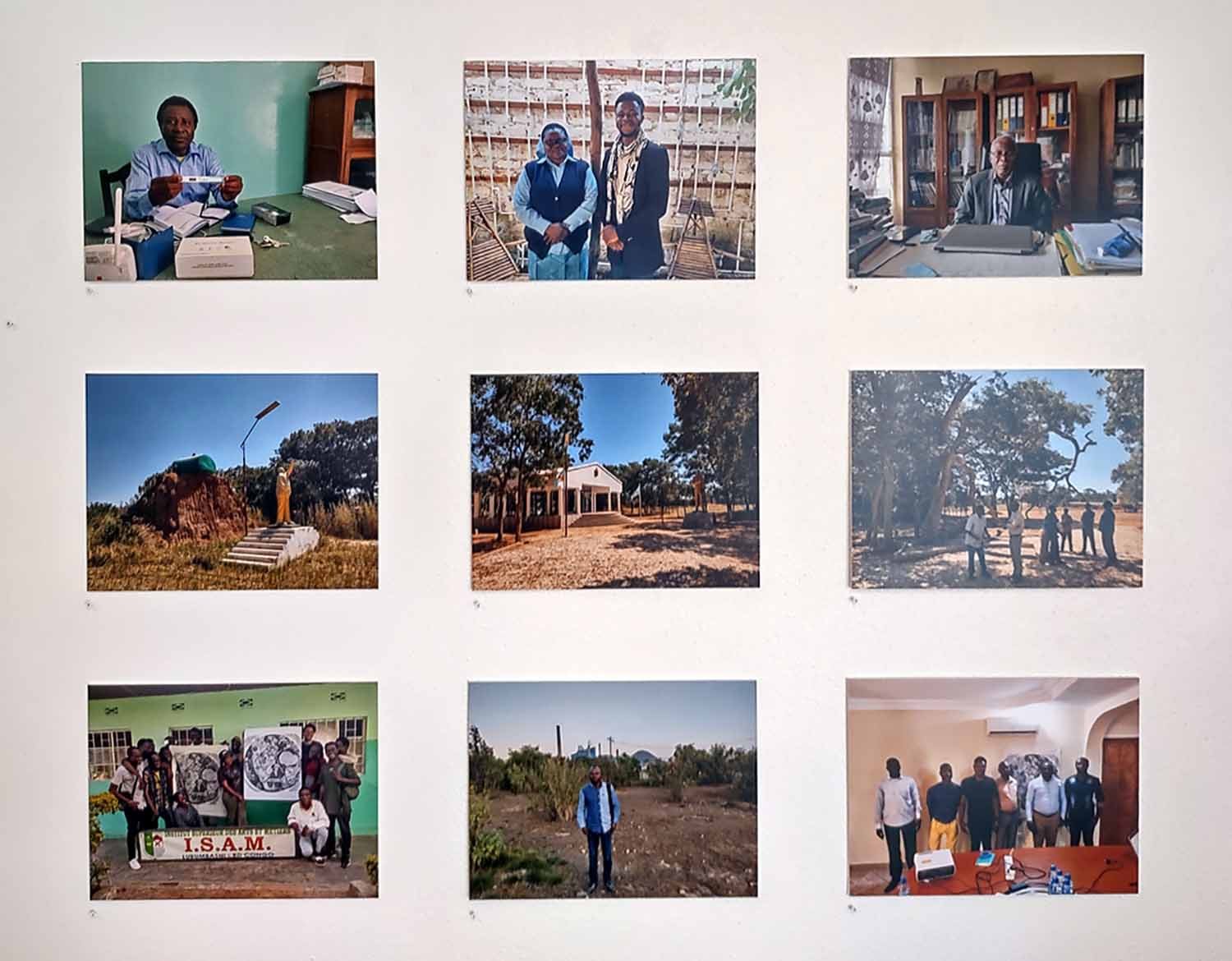

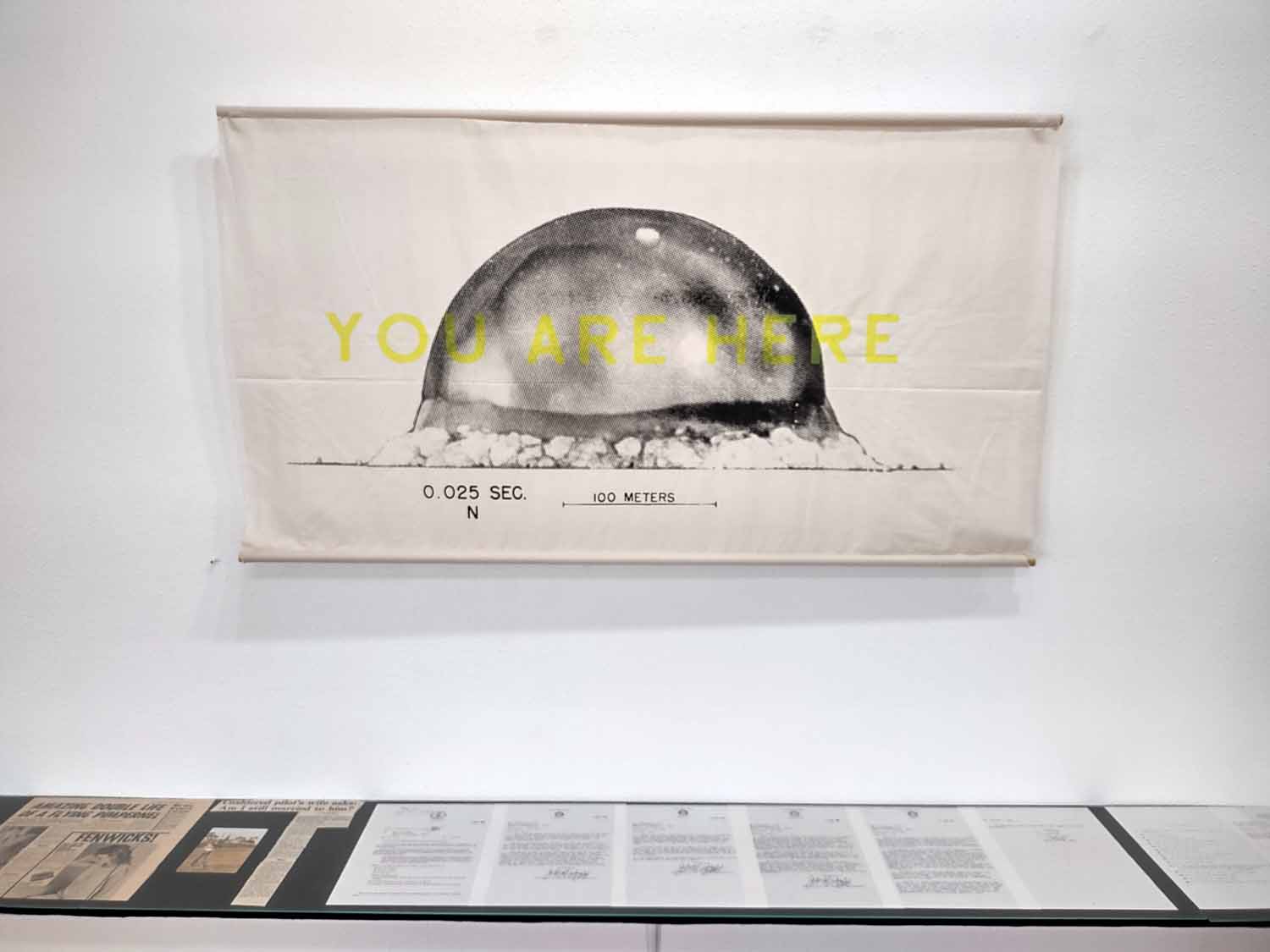

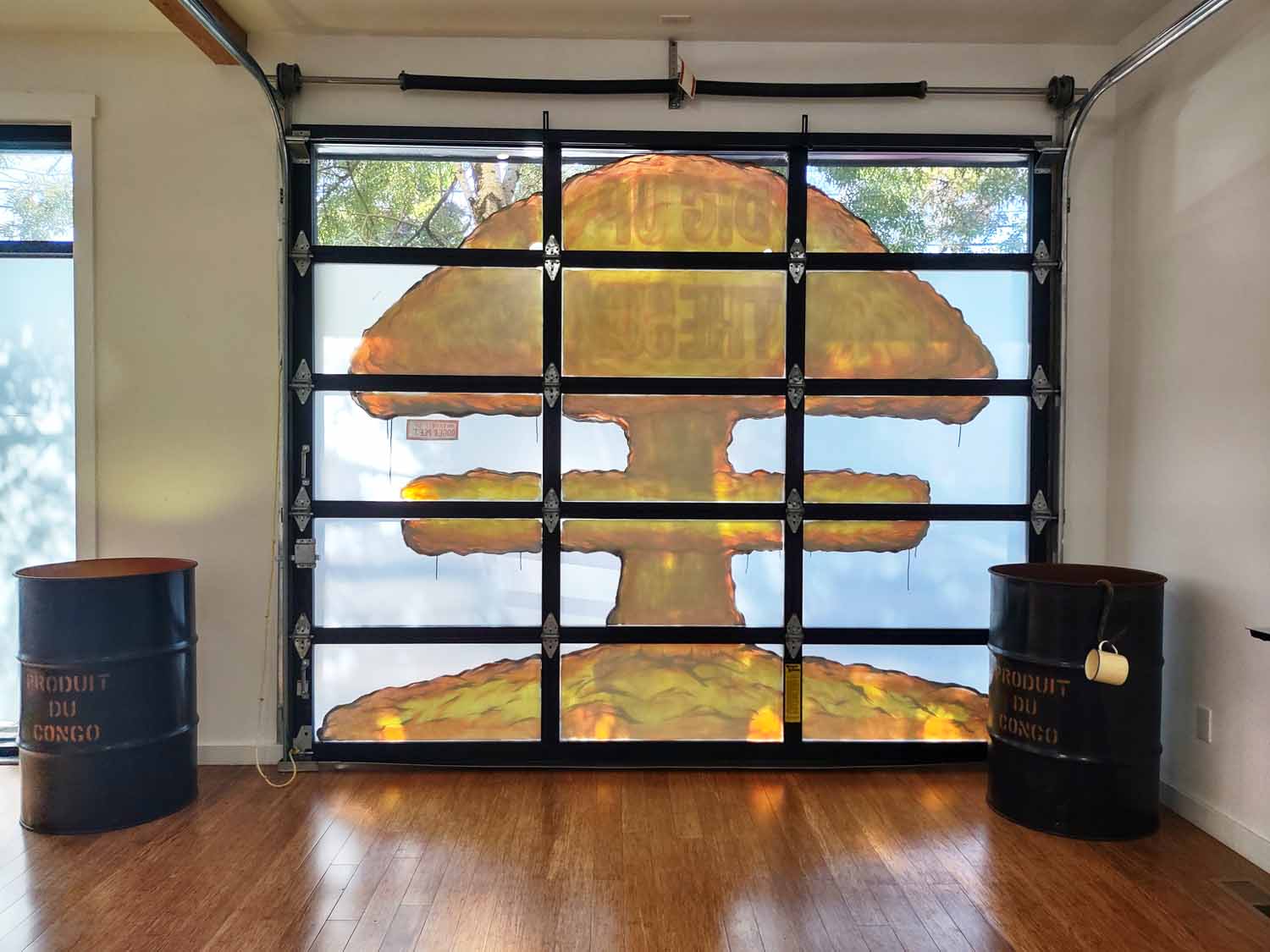

In October of 2023 I opened a show at Souvenir Gallery in Portland, OR, which pulls together a skein of projects from the past five years into one exhibit. The exhibit includes several distinct bodies of material. First is the big linocut map that traces the route taken by Congolese uranium through the Manhattan Project, along with the block from which it was printed, and a selection of the books that I used in the research for the image. Second is an installation of two steel barrels stenciled “Produit du Congo”, evocations of the barrels containing Congolese uranium that turn up over and over again in the history of atomic weapons and their aftermath. Third, a series of screenprints on fabric of images taken with rapatronic cameras that capture the first microseconds of nuclear explosions, accompanied with an array of photos, documents, newspapers and ephemera from the life of my father, Terence Peet. Fourth, a series of photographs taken during my visit to Lubumbashi, DRC in May of 2023.

The exhibit hours are Thursday-Saturday 12-5 pm, or by appointment via souvenirartspdx@gmail.com, with an artist talk October 14th at 2pm. Souvenir Gallery is at 1233 NE Alberta St in Portland OR. The exhibit is accompanied by an essay, reproduced here.

On the 29th of September 1965 my father, Terry Peet, awoke before dawn. He left his wife and two young daughters sleeping and drove to the Welsh coast, where he inflated a raft he’d checked out from the Royal Air Force base where he was a military helicopter instructor. He loaded scuba equipment into the raft, left a note in his car about going on one last dive even though it was getting dark, and then pushed the raft out into the cold dark swells of the Welsh channel. He watched it until the tide caught it and then walked up to the road and hitched into town.

He caught a train across the country to London where a connection in the Belgian Embassy gave him a ferry ticket and some money. He took another train to the ferry and boarded it. During the crossing he struck up a conversation with a young Canadian medical student and when the ferry arrived in Ostend they went to the same hotel. They spent the following week together, before he received orders to board a flight to the country known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

That woman was Joan Milner, and she would eventually become my mother. She had the same name as my father’s first wife; the one he left asleep in the dark before dawn.

My father went to Congo to fly helicopters for the CIA’s project to maintain control over the country during the chaotic post-independence period. America and Belgium had engineered the murder of the country’s first independent Prime Minister, Patrice Emery Lumumba, after he made it clear that he intended to use the country’s immense wealth for the benefit of its citizens, as opposed to the transnational conglomerates that had hitherto enjoyed its use. They killed him for wanting to claim rights of refusal over resources they had long considered their own, and for the next five years the country burned.

One of the most important resources that the Congo possessed was a mine called Shinkolobwe, which produced the most powerful uranium ore on the planet; the principal source of the highly concentrated radioactive material that had been used two decades previous to design, develop, and detonate the first atomic devices. The idea of Shinkolobwe passing out of American and Belgian control and into the hands of Africans was unacceptable to those august authorities, and they had closed it when Lumumba took power. Prior to Lumumba’s assassination the intelligence services of those two countries had engineered the secession of Katanga province, the mineral-rich region of Congo’s southeast where Shinkolobwe (among many other mines) was located. It was to Katanga that they sent Lumumba after they deposed him, and he was murdered, dismembered and dissolved in acid by Belgian agents less than 100 miles from the Shinkolobwe mine.

Five years later the country was in uproar as a nationwide guerrilla struggle to reclaim Lumumba’s legacy raged against the forces the Americans and Belgians were trying to install in its place. Into this maelstrom came a young British helicopter pilot, fresh from the incomprehensible act of abandoning his wife and two young daughters in their sleep, in search of a new self. He wanted to matter to the world and to history, and he imagined that he might achieve that by coming to the aid of Congo’s Belgian settlers. Those settlers were gibbering about the injustice of independence, telling dark lies about the brutality they experienced, screaming about being dispossessed of the territory they had claimed in Congo by the people they had enslaved to work it. My father thought he could fashion an identity for himself by rescuing them from the mythical fury of the people they had so long dispossessed.

Somehow he had been recruited; the details are unclear, but the CIA needed pilots, good ones, and helicopter pilots were much in demand. Presumably a wage had been offered, but also just the prospect of adventure and a way out of everyday life for a man who saw himself as too good at what he did to stay home and show other people how to do it.

The CIA managed to install a man named Joseph-Desiré Mobutu as Prime Minister in 1965, just after my father’s arrival, and Mobutu ruled the country for the next 30 years with their approval. For a brief period in the first few years of Mobutu’s rule my father was his personal helicopter pilot, installed at the behest of American intelligence to report on conversations had on board the President’s helicopter, during flights to and from his luxurious yacht moored outside the capital.

My father’s welcome ran out, eventually, and he left Congo and traveled to Canada to recapitulate his relationship with my mother. He was now outside of the CIA’s protection, and a deserter from the Royal Air Force, and he found it difficult to justify what he had done to people who learned about it. He was eventually captured by British military police at the Hong Kong airport, stood trial in England for desertion, and served six months in prison.

After his death I received a box of documents which showed his attempts to find some proof of the fact that he had worked for the CIA, mostly unsuccessful- except for one letter from his former superior in Congo that acknowledged that he had indeed been a contract pilot for the Agency’s Congo effort- in addition to flying T-28s over rebel-held territory as part of the campaign to remove the last traces of Lumumba’s movement from the country. He spent much of the rest of his life trying to affirm his identity; to articulate to himself, and to others, that he had done what was necessary and good in the service of an effort that history would show to be honorable. It wasn’t, though, and he knew it. But he never knew anything of Shinkolobwe.

The Shinkolobwe mine is the reason that my father and mother met, the wound at the heart of the world where the stones were dug to bring the sun to earth, to bring into this world the thing of power that would allow those who controlled it to deny the future to anyone who stood against them. That place is forbidden now, a lost wasteland of rock and scrub that has been dug through a thousand times by the successive generations of Congolese people who do the work of hauling forth from the Earth the things that Capital has demanded, digging up the sun.

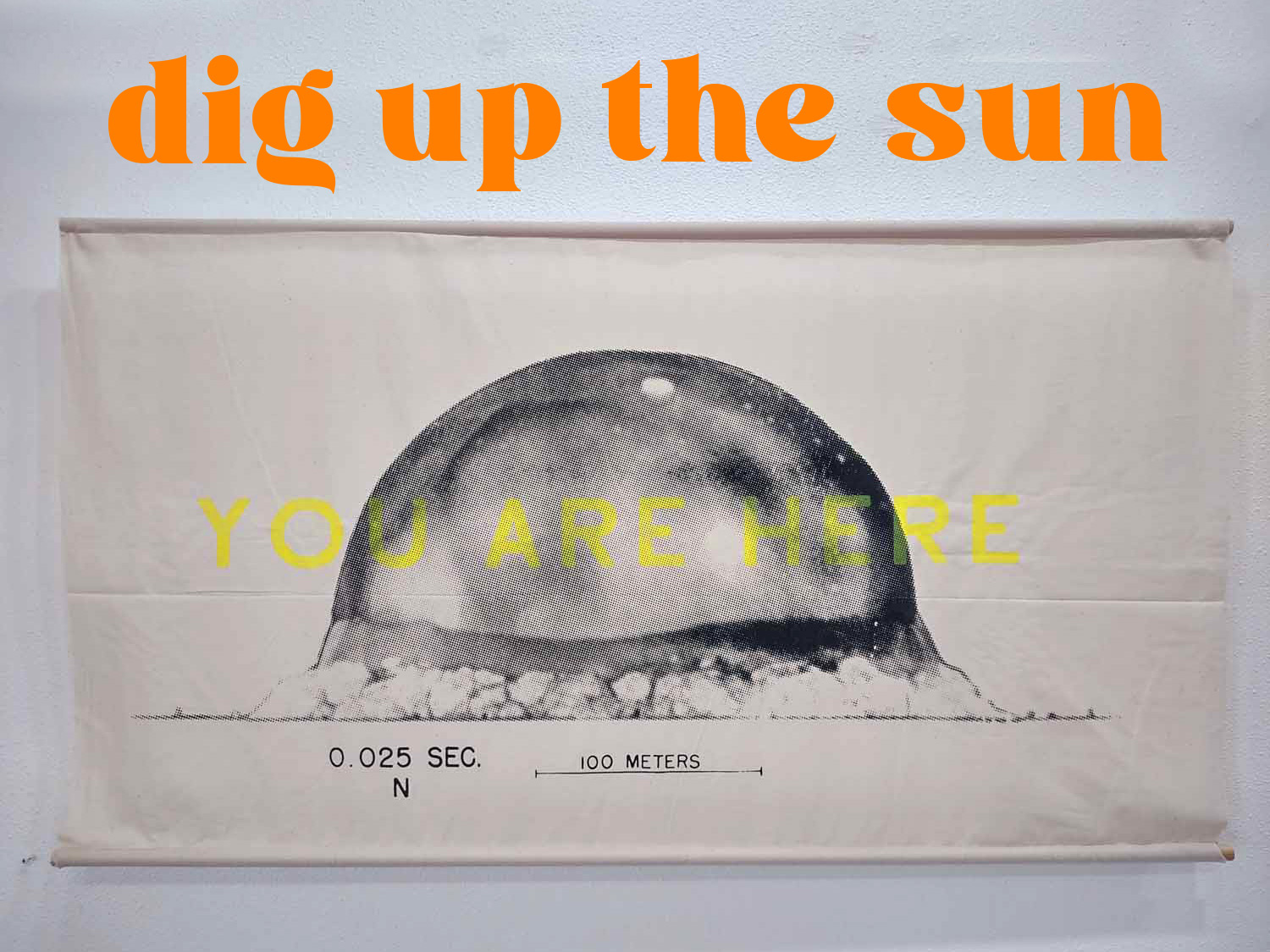

Those workers are not present in history. For a long time the mine was absent too; stricken from maps, kept wrapped in a formal secrecy whose gravity persists today in both Congo and the United States. But its grim magnetism has been uncloaked now, and we have to reckon with it. The lives we live are lost in its cold shadow, a black sphere inverted above us and reflected off the night itself. The stones of Shinkolobwe are in the plumes of radioactivity leaking from underground tanks at the Hanford reservation, they are in the water supply of the schools of East St. Louis and the cancer clusters of the Marshall Islands and the living memories of the hibakusha, the nuclear survivors of Japan. Those stones sat roadside for a decade at a Manhattan Project waste dump in Tonawanda, New York, in rusting metal barrels marked “Produit du Congo”, because the structures that had been built to contain them became too hot to manage, and so the barrels were removed and left out for the rain to wet. Images of the radioactive plume from the first nuclear test at the Trinity site in New Mexico show a cloud of radionuclides spreading across the entire continent. That is all Shinkolobwe.

This summer a film was shown in the cineplexes of the world about the man who shepherded the atomic bomb into the world, focusing with great sentiment on his profound feelings of unease about what he had unleashed. “When you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and do it ” said Oppenheimer, “and you argue about what to do about it only after you have had your technical success. That is the way it was with the atomic bomb.” That success was made possible by the stones of a Congolese mine, split and crushed until there was only the heart left to sunder. The work of science and war has taken the world so far apart, and ourselves so far apart from it, that we can no longer remember what it means to be inside it. We orbit it now, like electrons; weightless, barely even there. These are the first microseconds of the long nuclear future, and the only thing that remains of us is our desire to see everything end.

That’s what happened to my father, fleeing one world in search of another where he could be someone new- someone essential. But he was always essential. He betrayed everything in the service of empires that left him faceless in the dust, but his birthday is Congolese Independence Day. Like him, we will never find what we are looking for in the waste left behind by our investigations; we can only find it in the things we do as ensemble. Not taken apart, but taken together, forever. Into the future.

The mine is family. It’s my ancestor. It’s the reason I’m here.

It’s the reason you’re here.

Welcome.

This exhibit received support from the Regional Arts and Culture Council.