Under the Idaho desert heat the gravel and lava rocks sang a somber beat beneath our feet.

“What kind of ancestors do we want to be?” was the question posed throughout the Minidoka Pilgrimage. The Japanese American community had been surveilled by the U.S. government for at least ten years prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the issuing of Executive Order 9066 by President Franklin Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. This executive order authorized the forced removal of Japanese and Japanese Americans on the West Coast of the United States to “relocation centers”. More recently they have been renamed “American concentration camps.”

Take only what you can carry.

Bainbridge Island, in Washington state, was the first area where Japanese families were forcibly removed from their homes, businesses and farmland. (Learn more about the Bainbridge Island Japanese Exclusion Memorial.) Areas such as Camp Harmony (on current Washington State Fair grounds) were some of the first places families were taken. They were forced to live in horse stalls until their next train ride of uncertainty to far off “relocation centers.” Under Executive Order 9066 over 75,000 people of Japanese ancestry with American citizenship were detained.

Minidoka Relocation Center was one of the ten main camps on the west coast, though there are at least records of 75 all over the United States during WWII. Every year there are pilgrimages to these main sites of incarceration as a way to remember, honor survivors, heal and strive for a future where this never happens again. Due to the pandemic, the Minidoka Pilgrimage had not been in person since 2019. I attended that year as a fellowship scholar recipient. As someone whose family has been directly impacted by immigrant detention within the last ten plus years I was really interested in understanding more of this history that has impacted the Japanese American population so greatly.

We are living ancestors.

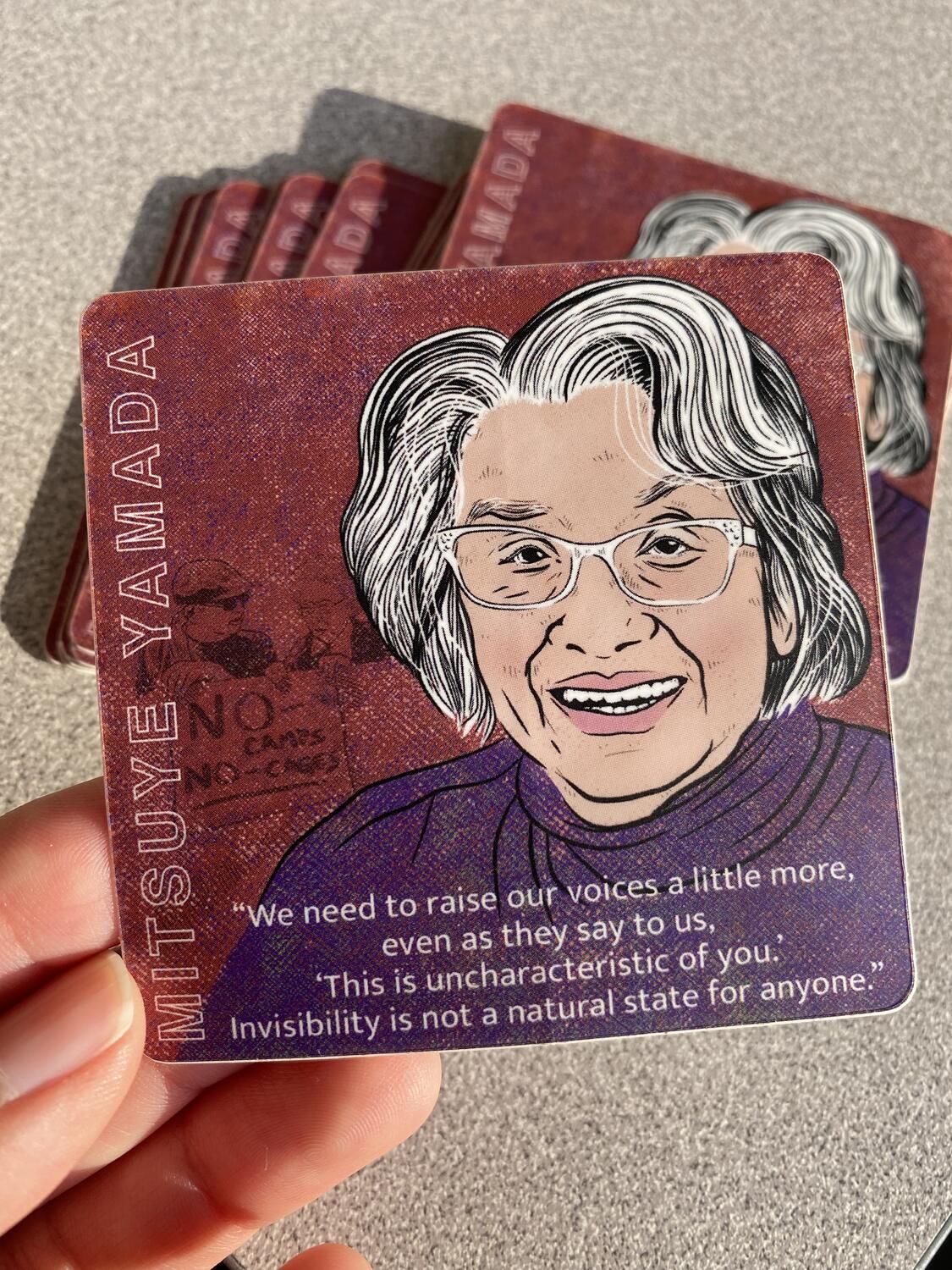

The Minidoka Pilgrimage offers a day-long educational program followed by a day on site at Minidoka. This year speakers included a keynote by poet Brandon Shimoda, a special message from author Mitsuye Yamada (who is a Minidoka survivor who recently celebrated her 100th birthday), and more filmmakers, artists, community organizers, archaeologists and historians.

This forced relocation and incarceration happened just 80 years ago. The most impactful moments for me during the Pilgrimage were the opportunities to listen to survivors who grew up in Minidoka. What they remembered from their childhood: only bring what you could carry; many belongings left behind, burned in the yard, sold for cheap or never returned; playing in front of the guard towers where soldiers had rifles pointed at them; the demeanor of their parents changing under such abrupt and inhumane conditions.

A mattress was lured up to the top of a vacant watchtower. After lovemaking and a cigarette the tower was illuminated.

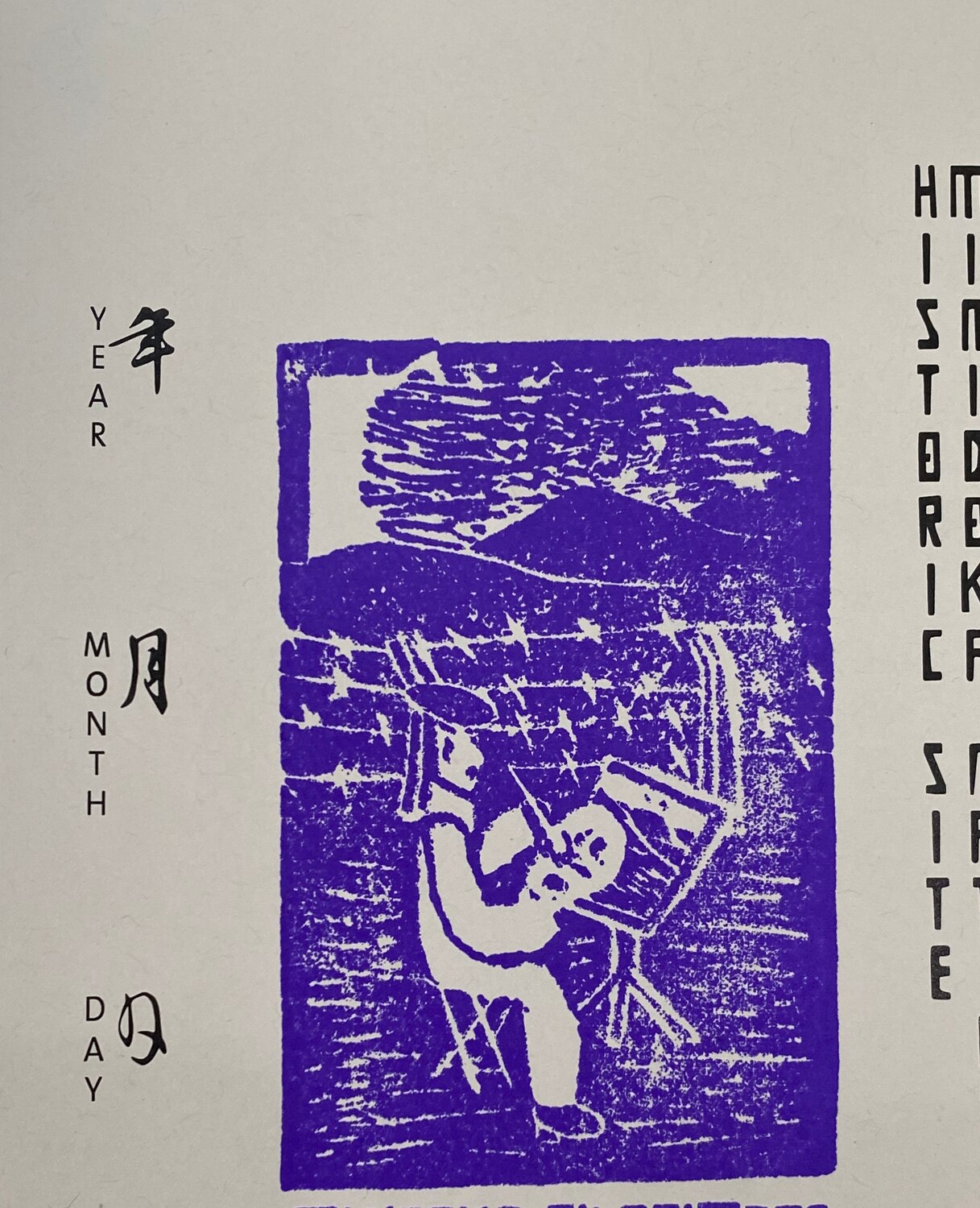

Minidoka was created and managed by the “War Relocation Authority” (WRA). They constructed military style barracks with surrounding community members where families were housed together, only separated by bed sheets for minimal privacy. Over 13,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans were taken from Washington, Oregon and Alaska to ‘Hunt Camp’ at the Minidoka Relocation Center between August 1942 and October 1945.

Workers in the mess hall dusted the plates of desert sand before serving the food.

Minidoka translates to “place of water,” however, this camp was right in the middle of the Idaho desert. Dust and sand would blow through the cracks of the barracks and mess halls. When the rains came, the grounds turned to mud. Before barbed wire fences enclosed the families even more, makeshift paths from volcanic rock were brought to the camp from the surrounding desert by incarcerees. (Barracks had other purposes after the war. Some such as the one that was returned to the historic site were used for migrant worker housing.)

Gardens were also constructed to distinguish between the cloned barracks and their own subtle protest of the conditions. While incarcerated at Minidoka, Mr. Fujitaro Kubota designed what is known as the Victory Garden that still stands at the historic site. He is also known for designing the Kubota Garden in Seattle.

Stop repeating history.

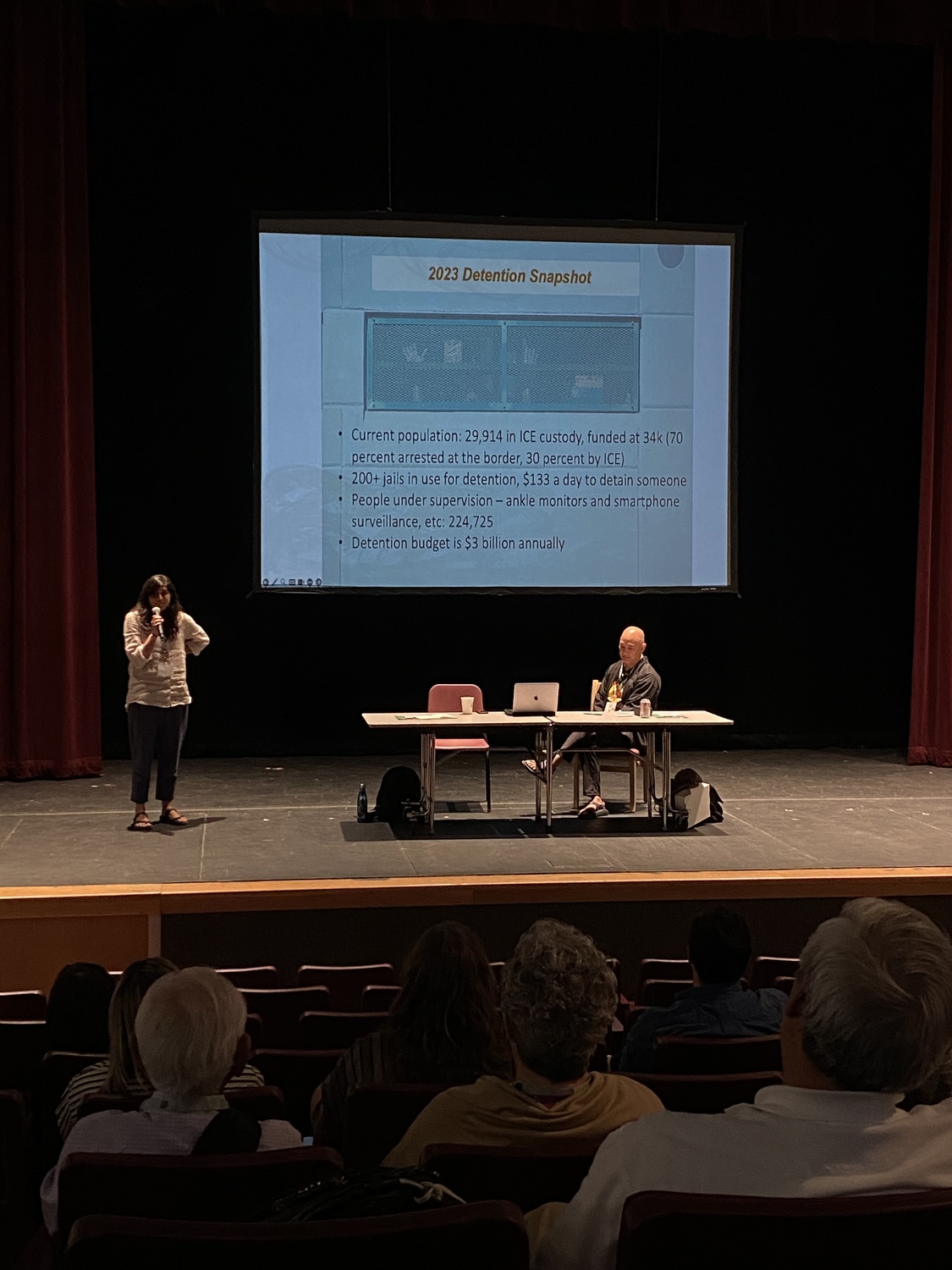

This year’s pilgrimage also had calls to action. Organizations like Detention Watch Network and Tsuru for Solidarity were present to share about the increase of immigrant detention and campaigns to stop further detention centers for children from opening. (In 2019, six camp survivors went to Fort Sill, Oklahoma to stop the reuse of a previous site of Japanese American incarceration from becoming a detention center to 1,400 asylum-seeking children.) Detention Watch Network Executive Director Silky Shah shared that 29,914 people are currently in Immigration & Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) custody with 70{4e6932a869a7dc6e53218b6c4700540ba226cfd2b19b5c8dbd46dbf9a28a9134} of them being arrested at the border and 30{4e6932a869a7dc6e53218b6c4700540ba226cfd2b19b5c8dbd46dbf9a28a9134} by ICE. “Detention Watch Network is a national coalition building power through collective advocacy, grassroots organizing, and strategic communications to abolish immigration detention in the United States”. (via Detention Watch Network) There are currently more than 200 jails in use of immigrant detention in the United States that receive $133 a day for detaining someone. The detention budget is $3 billion annually. There are currently 224,725 people in the United States under supervision via ankle monitors and smart phone surveillance systems. Tsuru for Solidarity’s Co-founder Mike Ishii about the more recent campaigns to stop detaining immigrant children and about a report issued demonstrating how children detained are being punished for showing signs of trauma (Read the Punishing Trauma report here.)

A couple of the campaigns they are both pushing include “Communities Not Cages,” a campaign to shut down existing detention centers and stop new ones from opening. Since this campaign launched in 2018, over 20 detention centers have won through local, state, and federal levels. Currently there is a big push to not renew contracts for the Elizabeth Detention Center in New Jersey and the Farmville Detention Center in Virginia. There is also the campaign to Shut Down the Greensboro Piedmont Academy that is an unlicensed facility that was a former boarding school. Greensboro has the capacity for 800 beds that would be monitored by private contractors that would be gilded prison. (Immigrant Legal Resource Center issued a report in May of 2023 that demonstrate the “Carceral Carousel” how sites of incarceration are being turned into detention centers.

Tsuru for Solidarity’s mission is to: “educate, advocate, and protest to close all U.S. concentration camps; build solidarity with other communities of color that have experienced forced removal, detention, deportation, separation of families, and other forms of racial and state violence; coordinate intergenerational, cross-community healing circles addressing the trauma of our shared histories.” (Via Tsuru for Solidarity and read about more current Tsuru Campaigns.) I have also benefited from a healing circle training offered by Tsuru to those of us organizing to shut down the detention center in Tacoma, Washington. Tsuru members continue to be consistent accomplices in that organizing effort.

#StopLavaRidge

In addition to wanting to support friends organizing the pilgrimage who are descendants of Minidoka survivors, I was especially interested in returning to Minidoka this year because there has been an ongoing fight to stop the Lava Ridge Energy Project that would be constructed two miles from the historic site. The proposal would create 400 wind energy generating turbines on a stretch of 73,000 acres of property owned by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). “If built, it will be one of the largest in the U.S. Several turbines are slated to be installed on the historic footprint of the camp, and almost all are completely visible from the WWII Japanese American incarceration site in Southern Idaho.” (Via Minidoka Pilgrimage and learn more about the Lava Ridge Wind Farm.)

The Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) made the grave mistake of labeling Japanese Americans and Native Americans visiting Minidoka as “Tourists and Recreationists” when this site is being protected as an area for reflection and healing for all of the survivors of forced incarceration, their descendants and all those who choose to visit this International Site of Conscience. Minidoka survivors and their descendants have been in an uproar and working to stop this project from happening. Not to mention that many neighbors and the local tribe are in opposition of this project. The DEIS also failed to articulate the integral importance to preserve the cultural and natural landscape. Minidoka National Historic Site educates all visitors on “righting a wrong”, civil rights and the multigenerational trauma inflicted by this forced incarceration. There is no mention of any potential trauma caused by this wrong mentioned in the DEIS. (Only civil rights violations are mentioned in the brief historical summary of the incarceration in the beginning of the document.) The DEIS also does not protect the viewshed from the Minidoka National Historic Site. The report draft states a “moderate” degree of visual change that will not protect the integrity of the Minidoka Historic Site.

Under the shade of rose bush a snake leaves behind old skin they can no longer carry.

The draft also did not entail further information on any migratory species including the bald eagle, greater sage-grouse, bats, mule deer and pronghorn that may be impacted by the installation of the 400 wind towers. The cumulative impact of the lifetime of the project is ultimately negatively impacting all of these populations in addition to all of the ground disturbances. We are amidst the Earth’s sixth mass extinction and anything we can do to mitigate further negative impacts to biological diversity.

The Minidoka Pilgrimage Planning Committee has a call to action posted on their website. You can sign a letter to oppose the Lava Ridge project that will be sent to Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland. Survivors, descendants and allies are encouraged to sign on by August 4, 2023. (Read the full Call to Action here.)

You can learn more about the Minidoka Pilgrimage or find an annual pilgrimage at a site near you.

Amidst witnessing tear of descendants of those incarcerated seeing the names of their relatives on the Honor Roll board, the solace of walking along human made gravel paths near the barbed wire fence, standing under the shade of the black locust trees that once shaded families on the hottest of days in the camp, the Minidoka Pilgrimage ensured a sense of joy in the celebration of culture. Social hours and meals together offered more space for storytelling, and community connection through karaoke and traditional dance. That too is an act of resistance as many people continued to dance and host celebrations while incarcerated. Parents tried to make the best situation possible for their children in such uncertain and fearful times.

What kind of ancestors do we want to be?

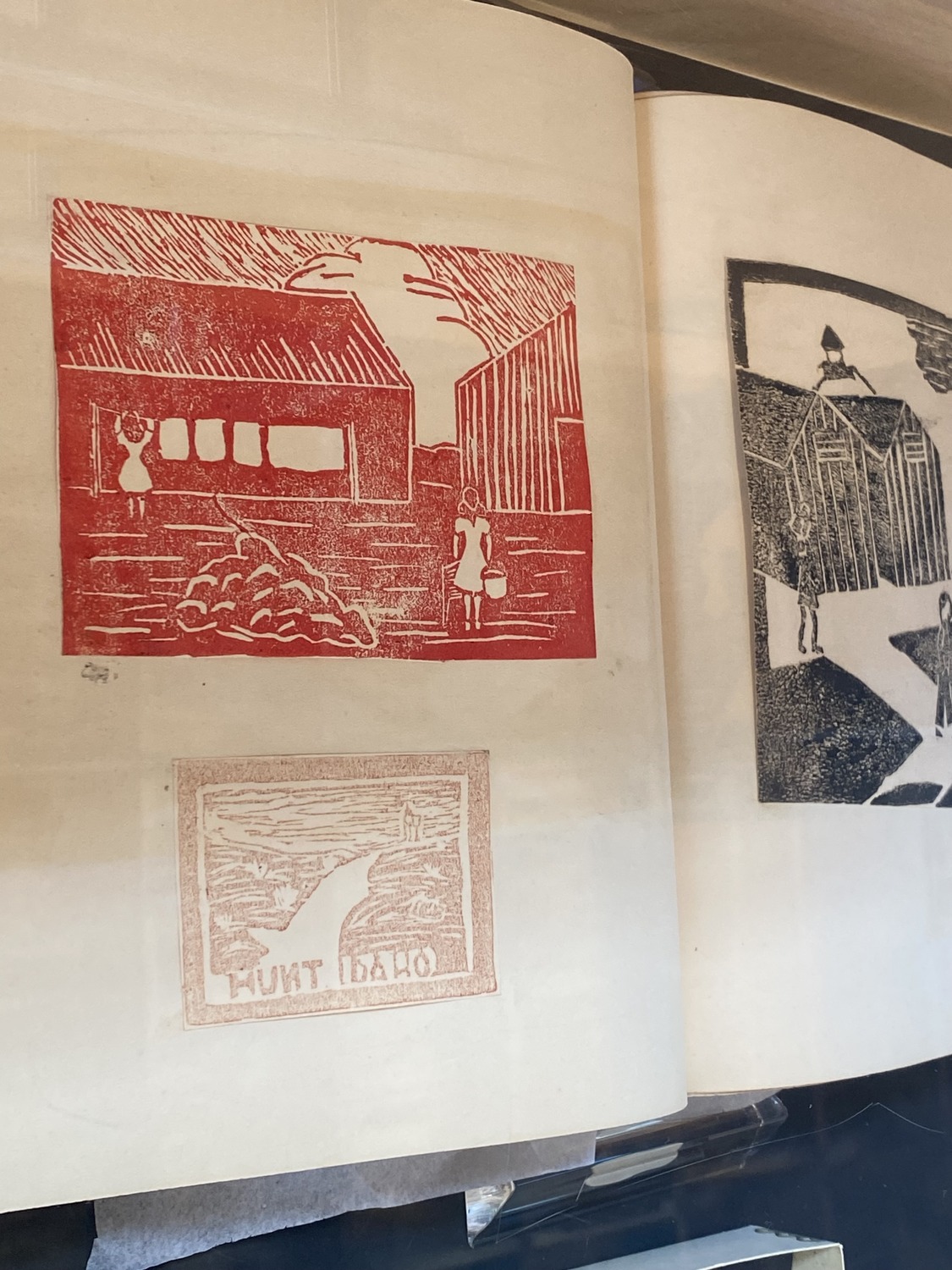

(The main featured photo is of block prints made during the incarceration at Minidoka that are on display at the Minidoka Visitor Center. Photo by Saiyare Refaei, July 2023)