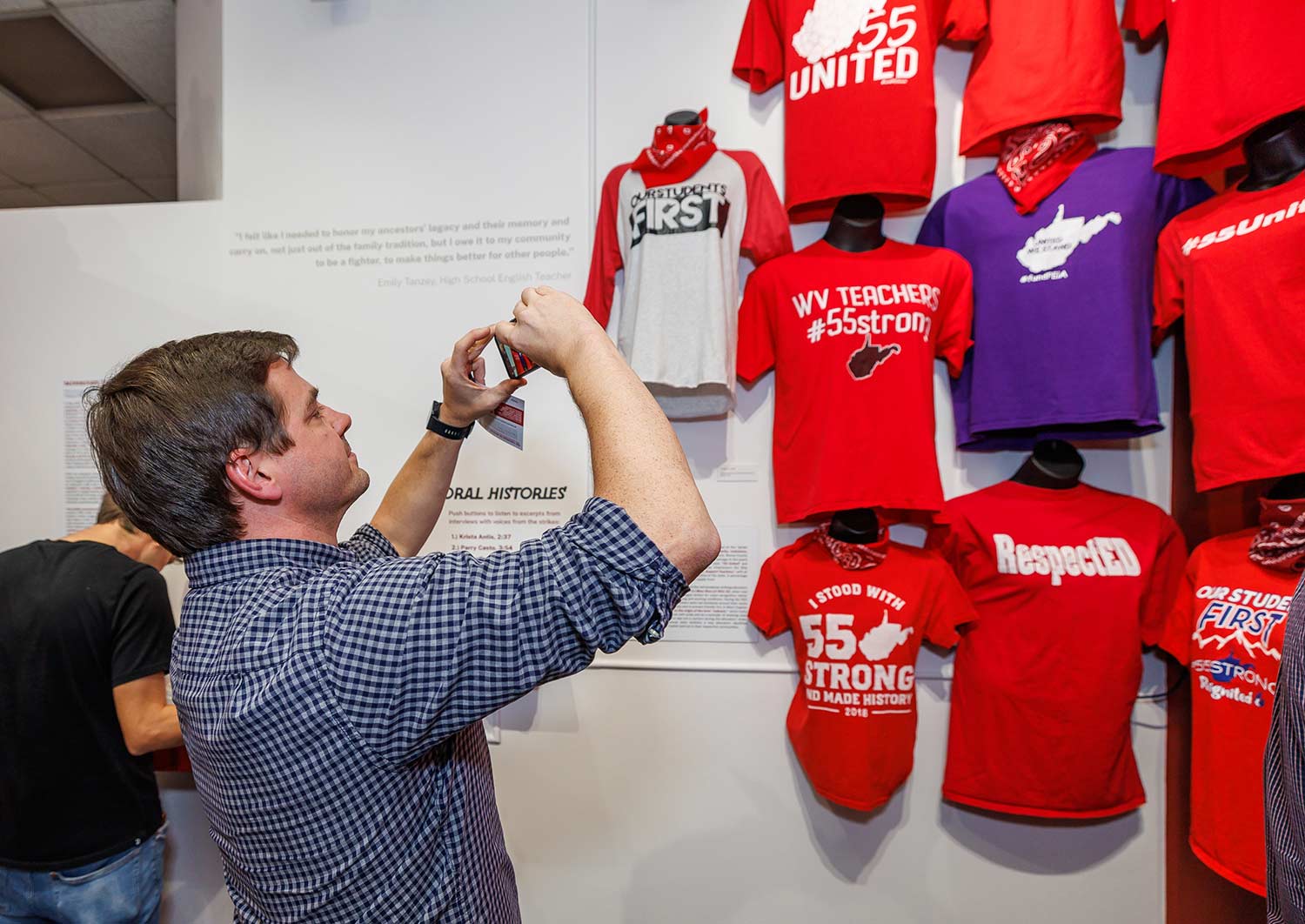

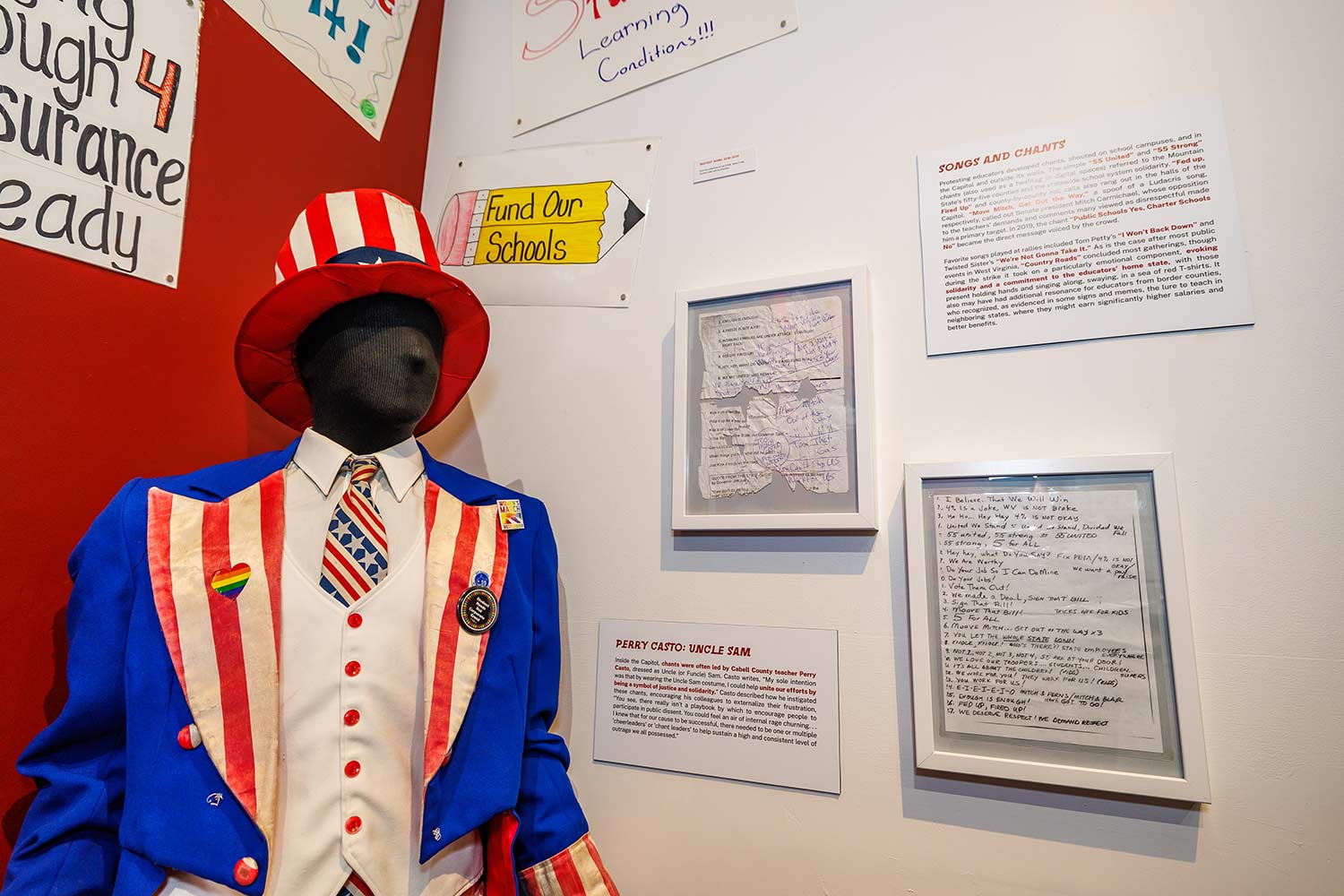

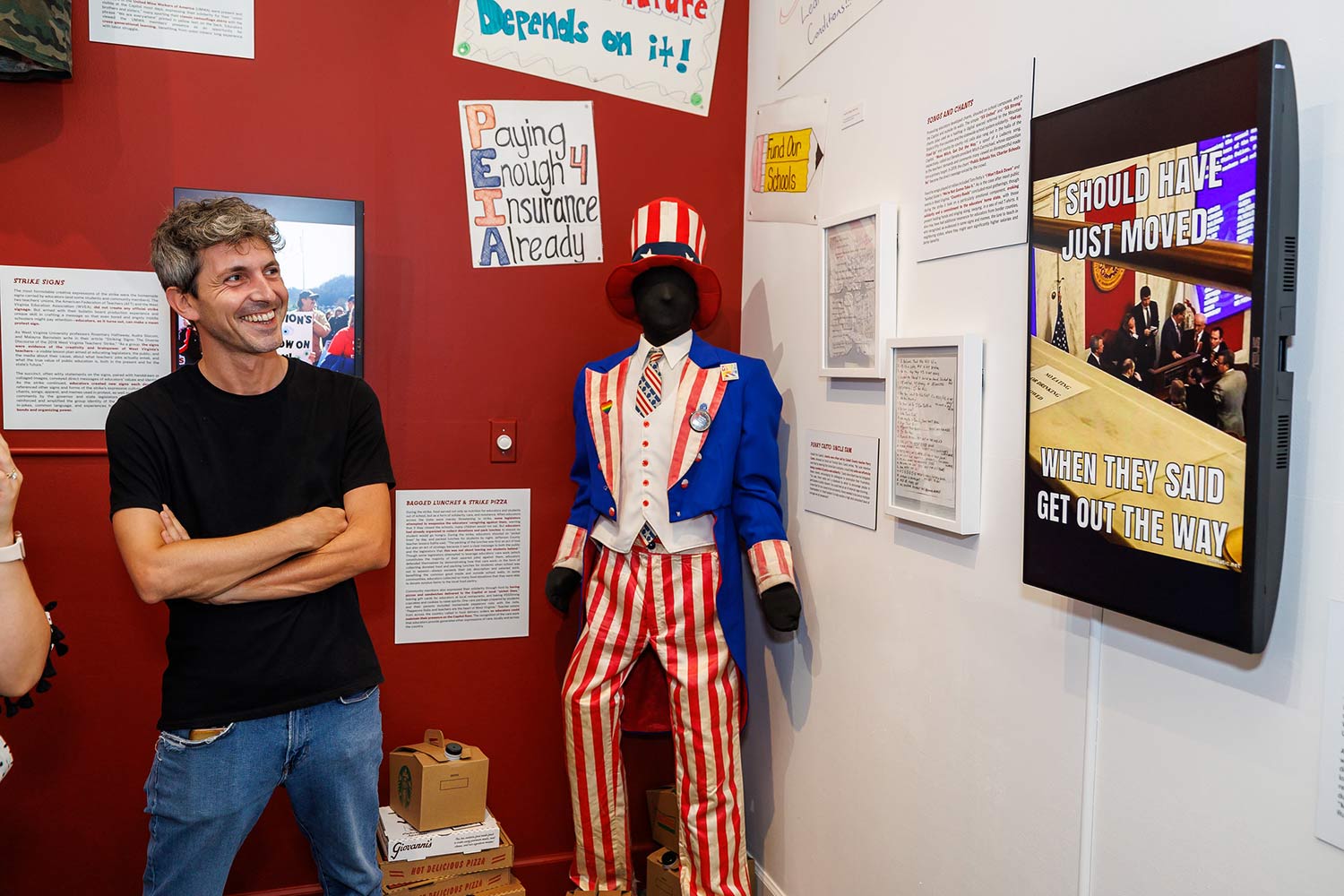

In August, the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum opened a new exhibit in our Solidarity Gallery. The Children of Mother Jones: West Virginia Educators’ Strikes as Care Work, presents the material culture of the historic 1990, 2018, and 2019 statewide strikes in which teachers and service staff struck for better wages, better health insurance, and in many ways for the basic recognition that their jobs position them as centerholders in their communities on a daily basis. This new exhibit is focused on the things people made during the strike, like t-shirts and buttons, protest signs and memes, to express solidarity amongst themselves and in their communities, and build power through reinforcing their own resistant culture. By positioning this work alongside the struggles for justice and unionization in the same region in the early 1900s (the museum’s primary focus), we begin to draw parallels through collective memory and the history of working class struggles in the US.

Children of Mother Jones is built from a central narrative written by museum board member Emily Hilliard, author of the fantastic Making Our Future: Visionary Folklore and Everyday Culture in Appalachia (University of North Carolina Press, 2022). Hilliard’s interest and writing is focused on the way in which people in Appalachia build and maintain folklore, which she defines as “the art of everyday life–creative practices we learn by living our lives, passed informally from person-to-person rather than through formal training.” People often don’t talk about this kind of “making” when we’re doing it, and, particularly in movement work, the things we create are often a means to an end, existing largely in the moment. After that hot moment, more often than not, protest signs and other creations often simply cease to seem relevant. If someone doesn’t save this work or otherwise uplift it, we tend to move on, either continuing the fight in new ways, or getting on with other aspects of our lives. Working with memory and history involves bringing these objects back into focus and asserting the power that they hold. And yes, even memes from a Facebook group can be understood as meaningful expressions of struggle: laughter itself is an incredibly powerful tool!

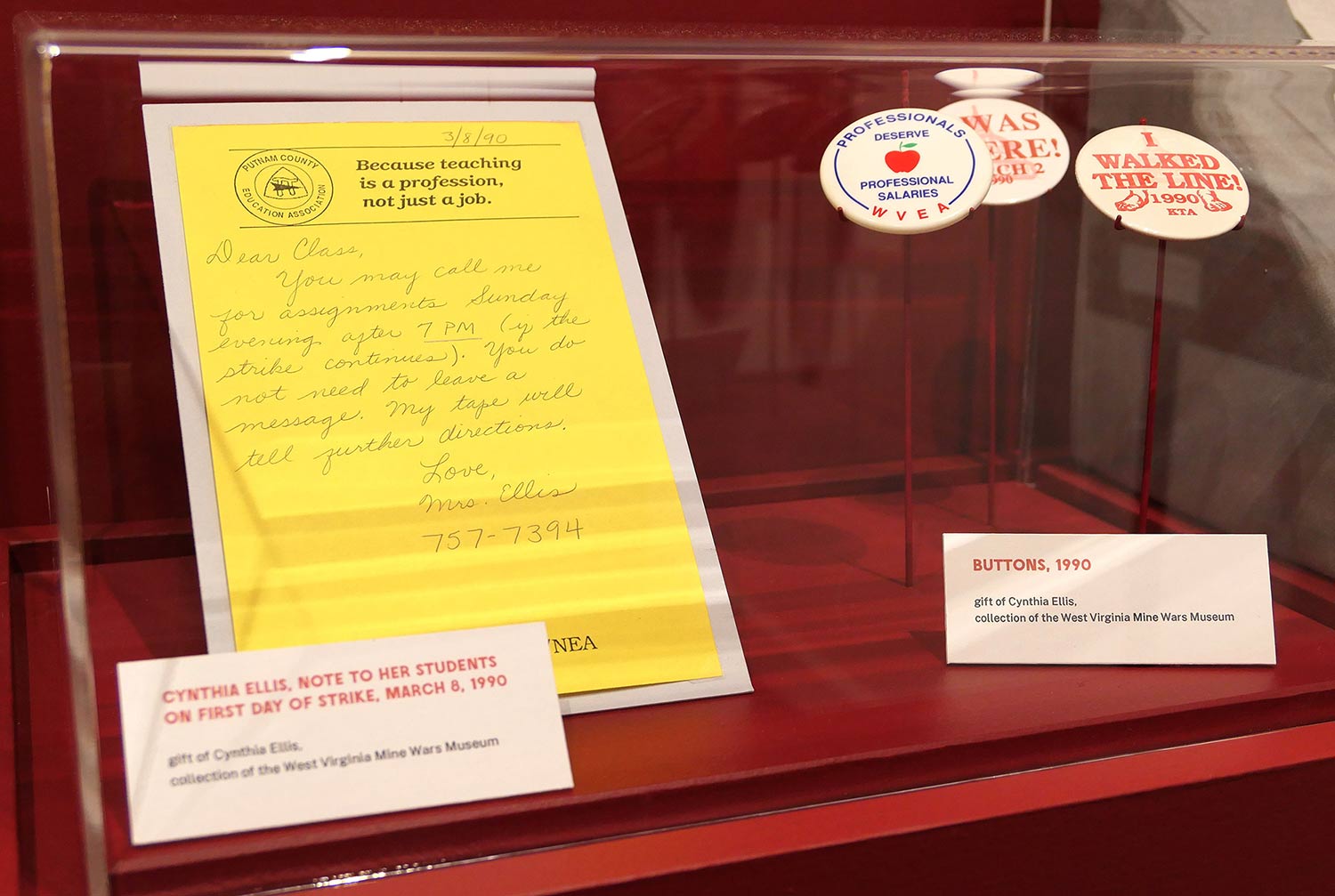

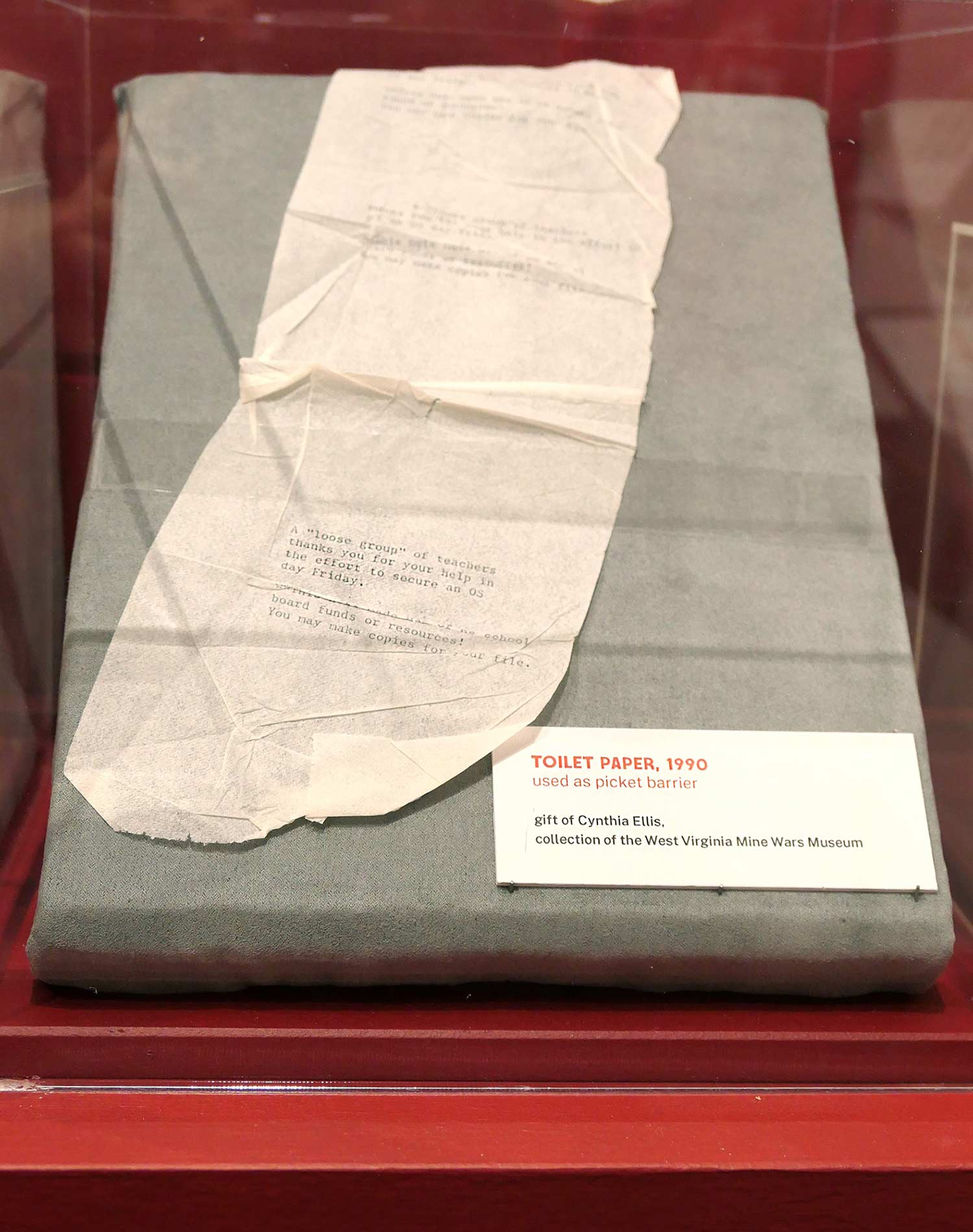

My work was to design and build this exhibit, and the materials that I pulled together were loaned by teachers through several call-outs over the beginning of the year. It’s slow work, gathering materials like these, and involves a lot of trust from the community and commitment from us at the museum. One surprise donation to the museum’s collection by Putnam County, West Virginia teacher Cynthia Ellis, included objects and papers from an earlier teachers’ strike in 1990, which allowed us to expand the scope of the exhibit to include historical tactics from a prior generation of union educators. The 2018 strike, for example, was organized largely outside of the boundaries of the unions through venting and sharing on a Facebook page, which grew rapidly into the locus of a state-wide, coordinated movement which went wildcat when it became necessary. In 1990, the communication landscape was entirely different, and endless late-night phone trees, television news, and full-page ads in local papers paid for by teachers were integral to the movement. People’s struggles for justice use the tools closely at hand, the ones we understand most intimately. Tying generations together – another integral part of memory work and the work we’re doing at the museum – allows us to better learn from the movement that was building before us.

Nicole McCormick recorded nearly a dozen oral history interviews with voices from the 2018 and 2019 strikes, recordings which really serve as the beating heart of the exhibit. Here, people talk most intimately about how it felt to be involved in the 2018 and 2019 strikes, how the events radicalized them, the impacts on their families and communities, the power and exhaustion they often felt. I listened to many of these recordings while I worked on the exhibit details, and I was consistently stopped in my work by the earnesty of the words of the people who found themselves in the maelstrom and fervor of the moment. In order to share this in short, easy to digest pieces in the exhibit, I installed a small media player in a classic tin lunchbox, with buttons that visitors can press to listen to short edited clips of three of the interviews. All of the recordings are available in their entirety online at the museum’s website, and I recommend them highly.

“Care work” is a recurring theme in the interviews, and in the threads Hilliard tugs at in her chapter on the teachers’ strike in Making Our Future. Teachers, particularly in rural areas, take on much more responsibility for their communities than just clocking in, teaching lessons, and clocking out. Lunches and other mutual aid structures were a prerequisite to the strike, preempting the typical alarmist cries in media that the students would be the first to suffer. The demographics of teaching in West Virginia skew heavily towards women’s labor, and in dealing with an all-male state legislature that seemed to have a “get back into the kitchen” attitude about the movement, sexism comes up in many of the interviews as a particular source of the rage of the teachers themselves. In Appalachia, “we see how labor intensive coal mining is and how harmful it is to their health, but we don’t see how labor intensive teaching is: care work is so hard” says English teacher Emily Tanzey. “It’s hard on our bodies, but also our hearts and souls and minds because of what we witness with all the secondary trauma” that teachers experience from being integral support providers within their communities.

Working on an exhibit in the context of a history museum that highlights material culture from events in recent memory put me in what sometimes felt like a sticky position. We work hard to keep our museum relevant, to bring the struggles in the coalfields 100 years ago into some parallel with present movements. The “sticky” part is working with the reality of how the people who participated directly in these events might see themselves reflected in the exhibit. Museum-izing a struggle that is in many ways still ongoing (the battle for dignified health care is still raging on, for example) runs the risk of alienating the very people who participated, and the only way we knew how to keep that from happening was by bringing in the voices and opinions of the teachers who were interested in working with us to the center of the project.

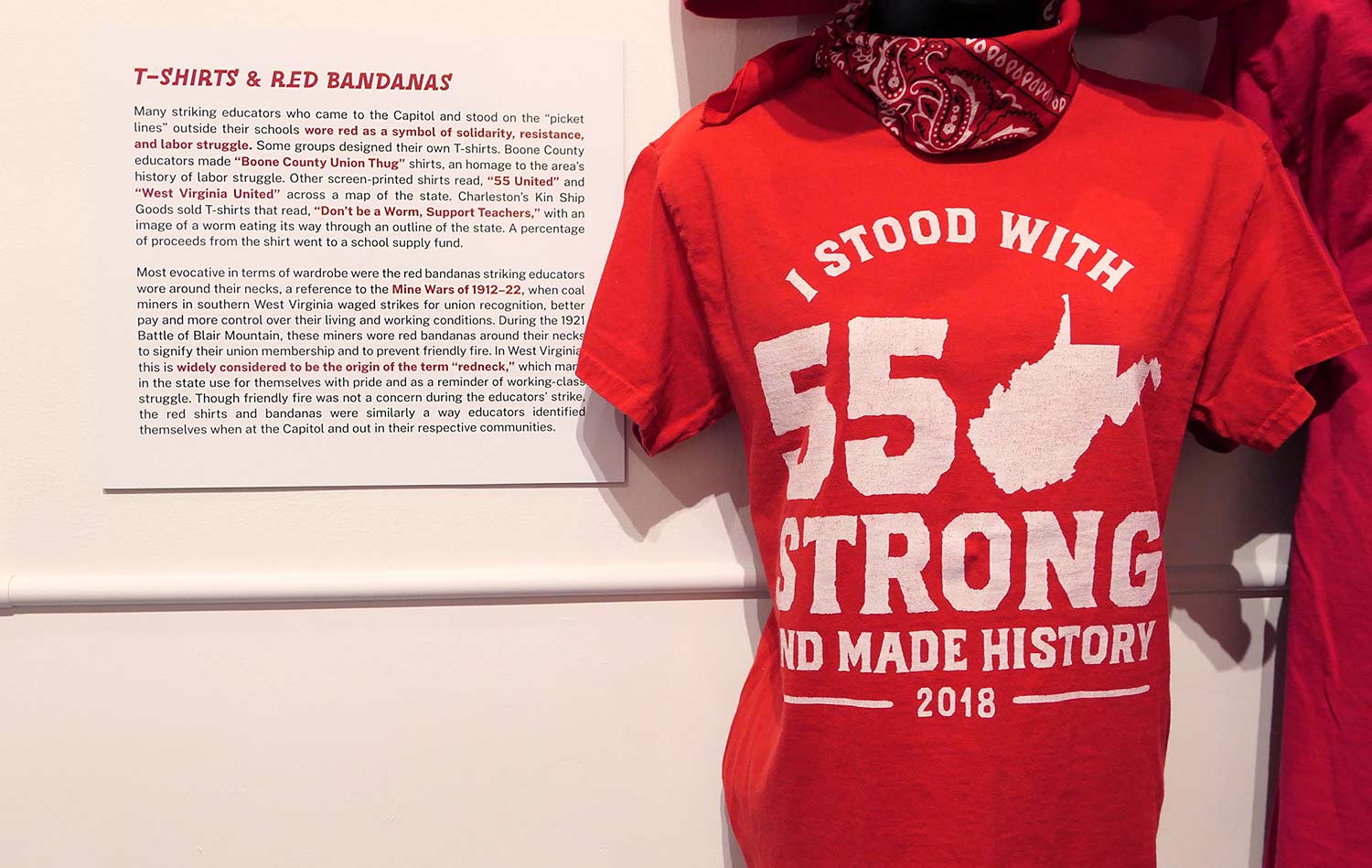

Exhibiting the cultural production of the teachers who were on the picket lines in 1990 and 2018-19 alongside the artifacts, photos, and stories of the unionist coal miners and their families who struggled during the Mine Wars era creates a space where visitors can experience the deep threads which weave working class struggles together over generations, threads which are contested and even erased from public memory if we aren’t vigilant. When we tell these stories alongside each other, our collective memory and capacity for resilience and courage grows. Teachers and service personnel knew this when they donned red paisley bandanas in 2018: a simple, easily available textile with deep symbolism in Appalachia, the red bandana was used as a battlefield signifier during the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain, and wearing one in certain settings today carries immense historical power as an expression of organized solidarity and commitment. Reflecting on the experience of the 2018 strike, and how their care work within their communities was ongoing even when they were occupying the state capital building for several days in Charleston, West Virginia, high school English teacher Krista Antis tells Nicole McCormick in her interview that “We were still educating. We were showing our kids how to stand up for themselves to a bully.”

The Children of Mother Jones: West Virginia Educators’ Strikes as Care Work will be on exhibit in the Solidarity Gallery at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan, WV through summer of 2024. The museum’s regular public hours are Wednesdays through Saturdays, 10am-5pm. We’re closed through the winter from November through February, but appointments can sometimes be made during this time. Find out more about visiting the museum here.

Solidarity Gallery is a space within the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum which features biannual exhibits that bridge art and history through multi-disciplinary creative practices that focus on artists’ interpretations of Mine Wars memory and extend the scope of the stories we tell.

See loads of excellent photos of the exhibit from opening night here, by Logan, WV photographer Dylan Vidovich.

Listen to the oral history interviews recorded by West Virginia music teacher Nicole McCormick in their entirety on the museum’s website.

And grab a copy of Emily Hilliard’s book from the museum’s shop!