Standard Explicit Version Now Includes: Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe [Remix] feat. Jay-Z

The moment that signaled 25-year-old Top Dawg Entertainment artist Kendrick Lamar’s rise from West Coast underground cult hero to mainstream superstar happened on stage at a hometown concert in during the summer of 2011. With Dr. Dre looking down from the balcony seats, Lamar was joined on stage by Snoop Dogg, Kurupt, and Game. Those West Coast icons, gangster rap torchbearers for two decades, crowded around Kendrick Lamar and hugged him and declared him the new king of the West Coast. The crowd starts chanting, Kendrick! Kendrick! Kendrick! and the way Lamar reacts begins to explain why his presence in rap, as a proudly ordinary and honest guy with an extraordinary gift, is so necessary and so refreshing: Kendrick Lamar gets choked up.

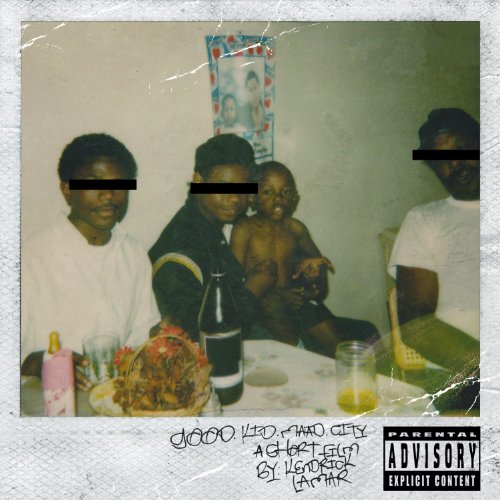

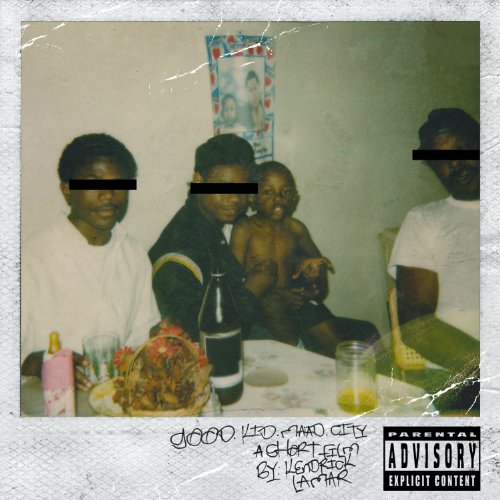

A little more than a year later, Lamar released the album that silenced listeners who doubted that he deserved to be crowned or thought he’d have to change to reach mainstream success. 2012’s good kid, m.A.A.d city, Lamar’s major label debut album, is a sprawling masterpiece of technical rapping and structured storytelling that defies and expands the conventions of his genre. It’s a classic album that feels like a classic movie, deftly weaving moments from Kendrick’s life together to form a narrative that becomes an empathetic ode to a troubled and dangerous place. Like a lot of eternal characters from literature and film and a lot of ordinary kids, Lamar finds himself torn between the temptation to do wrong and the wisdom to do right.

good kid, m.A.A.d city landed in the tiny overlap between popular adoration and critical respect, selling more copies in its first week than any other debut album in 2012 and earning massive nods from Pitchfork, The New York Times, MTV and hundreds of other outlets. Lamar raps with hypnotizing precision, in triple time and in different voices, recalling the moments of dizzying theatricality of Eminem’s The Slim Shady LP and combining them with the unglamorous grit of Nas’ Illmatic.

Long before Kendrick Lamar was redefining the boundaries of rap, he was a kid growing up in Compton in the 1990s, trying to stay out of trouble. I’m six years old, seein’ my uncles playing with shotguns, sellin’ dope in front of the apartment. My moms and pops never said nothing, ’cause they were young and living wild, too, he said in a 2011 interview. The mayhem going on around him couldn’t stop Lamar from getting good grades, but he found school frustrating: This is always in my head: There was a math question that I knew the answer to, but I was so scared to say it. Then this little chick said the answer and it was the right answer, my answer. That bothers me still to this day, bein’ scared of failure.

Lamar idolized Tupac Shakur growing up, and by 16, he’d recorded his first mixtape, under the name K. Dot. He’d also signed with Top Dawg Entertainment, now home to other L.A. up-and-comers like ScHoolboy Q, Ab-Soul, and Jay Rock. Lamar released a series of mixtapes as K. Dot, receiving cosigns from rappers like Lil Wayne and Game, before dropping the moniker and going by his birth name in 2009. I’ll always be K. Dot in Compton, he said. Kendrick Lamar’ is more mature and I can talk more about what I want to do with my life. I want my legacy to be about who I am as a person, not just as an artist. 2011’s Section.80, released independently through iTunes, moved thousands of copies with no promotion and established Lamar as an songwriter with something meaningful to say to his generation, one that hadn’t been spoken to with as much respect and conviction by any other artist. Lamar toured America behind Section.80, watching thousands of people scream every one of his words back to him, reveling in a connection with his fans that runs as deep as his lyrics.